The worship of Datuk Kong is one of the most peculiar Malaysian cultural practices. The Klang River Festival recently highlighted this syncretic Chinese worship of Malay land deities.

By CHIN JIAN WEI

The Klang River Festival was an annual festival presented by KongsiKL, aimed at sharing knowledge and inviting conversation on heritage, culture and identity. Various events such as art exhibitions, special discourses, workshops and installations were conducted throughout several iconic heritage buildings in Kuala Lumpur. Among the many activities celebrating Malaysian culture, the self-guided walk Datuk Gi Mana? and its associated dialogue session Finding Datuk Kong in Malaysia: The Origin and Function really stood out.

Datuk Kong, or sometimes known as Datuk Gong, has always been a figure that has existed in the periphery of the lives of many Malaysian Chinese. Sitting in a quiet corner of a car park, or tucked away inconspicuously behind a wet market or an auto repair shop, the ubiquitous red shrine is a very familiar sight. Unlike Buddhism, worship of Datuk Kong has never been institutionalised, meaning that there is no real canon or orthodox way to worship. The practice is passed down from generation to generation orally, resulting in great variation from location to location, as customs will change depending on the devotee’s environment and generation. Most Datuk Kong statues appear as old, bearded men, usually of Malay ethnicity, sporting a songkok and wielding a keris.

Dr Tan Ai Boay and Dr Andrew Loo Hong Chuang conducted the dialogue session on Dec 3, breaking down the different customs practised by Datuk Kong practitioners throughout Malaysia, as well as the possible origins behind the religion. “Datuk Kong is a form of syncretism in South-East Asia,” Dr Tan, a researcher of South-East Asian anthropology, said, referring to how different beliefs have combined together to produce Datuk Kong, a deity said to bring prosperity, peace, and well-being to the community that venerates it. “It is a fusion of Tudigong worship with Malay Keramat, which among other practices, venerate natural objects such as rocks.”

Tudigong is what Chinese people call the deity of the land. In many cases, these gods originated as historical individuals who came to the protection of their communities and were later deified. Thus, it would make sense that when Chinese immigrants first arrived at Malayan shores generations ago, the practice of worshipping Tudigong would become influenced by Keramat practices to become Datuk Kong. It would also explain why most Datuk Kong appear to be Malay.

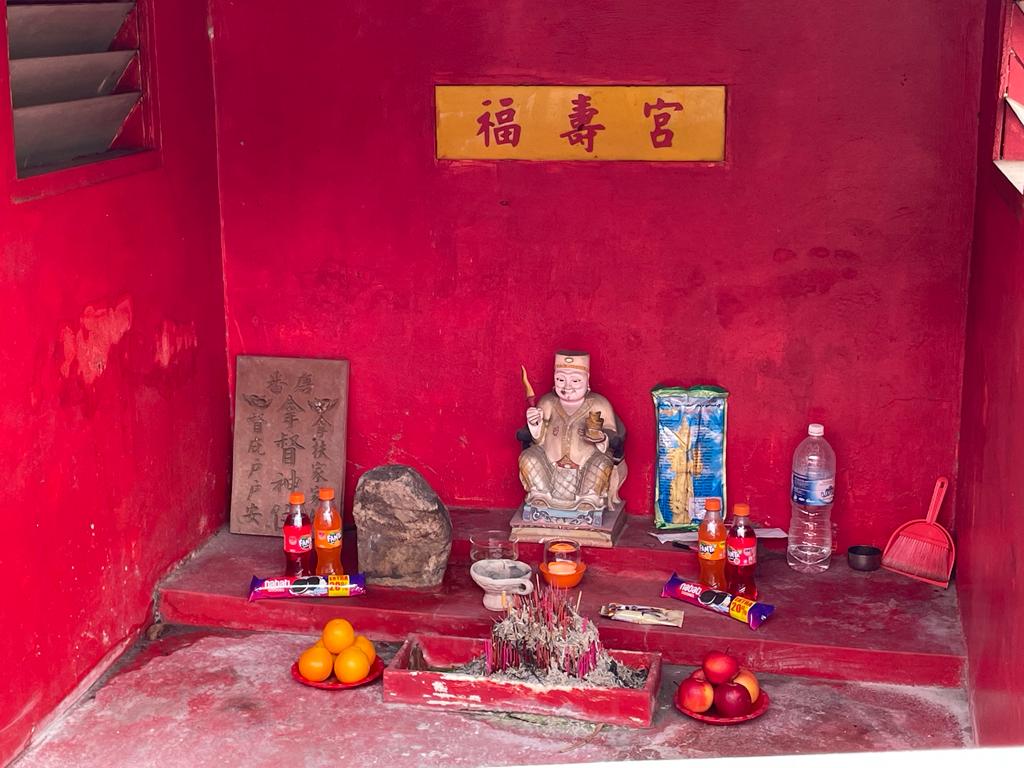

The intermixing of cultures is something quintessential to the Malaysian experience, and Datuk Kong is the perfect representation of this. While most statues seem to be Malay, there are also statues of Chinese, Indian, or aboriginal Datuk Kong. “The worship of Datuk Kong must include black coffee placed in the shrine,” Dr Tan commented on one of the only commonalities found throughout Datuk Kong worship in Malaysia. “Another practice would be the use of Kemenyan incense, which is also used in worship of certain Indian deities, but not the Buddha and bodhisattvas.” As Datuk Kong are usually Malay, only halal food offerings are permitted.

However, the variations found in Datuk Kong shrines are truly diverse. Some Datuk Kong are regarded as tigers or crocodiles by their devotees. Some shrines have no statues, and instead, a rock or anthill is worshipped in its place. Dr Tan showed us a shrine in a Chinese fishing village where saws from sawfish are venerated as Datuk Kong alongside the statue. Perhaps most startling were the sight of the grave of a Muslim saint as a Datuk Kong, and even the deification of the late politician Karpal Singh as a Datuk Kong in Perak.

The origins of Datuk Kong worship are hazy and lost to the sands of time. According to Dr Tan, the first epigraphic record of Datuk Kong dates back to the year 1886. Another source states that Datuk Kong had already been worshipped for 200 years by the year 1907, dating the practice to the early eighteenth century. Yet there is a passed-down belief that the first Datuk Kong was a Bugis man who helped resist the Portuguese invaders during the last days of the Melaka Sultanate in the early sixteenth century. As with so many other practices that are primarily passed down orally; it is difficult to conclusively ascertain an origin.

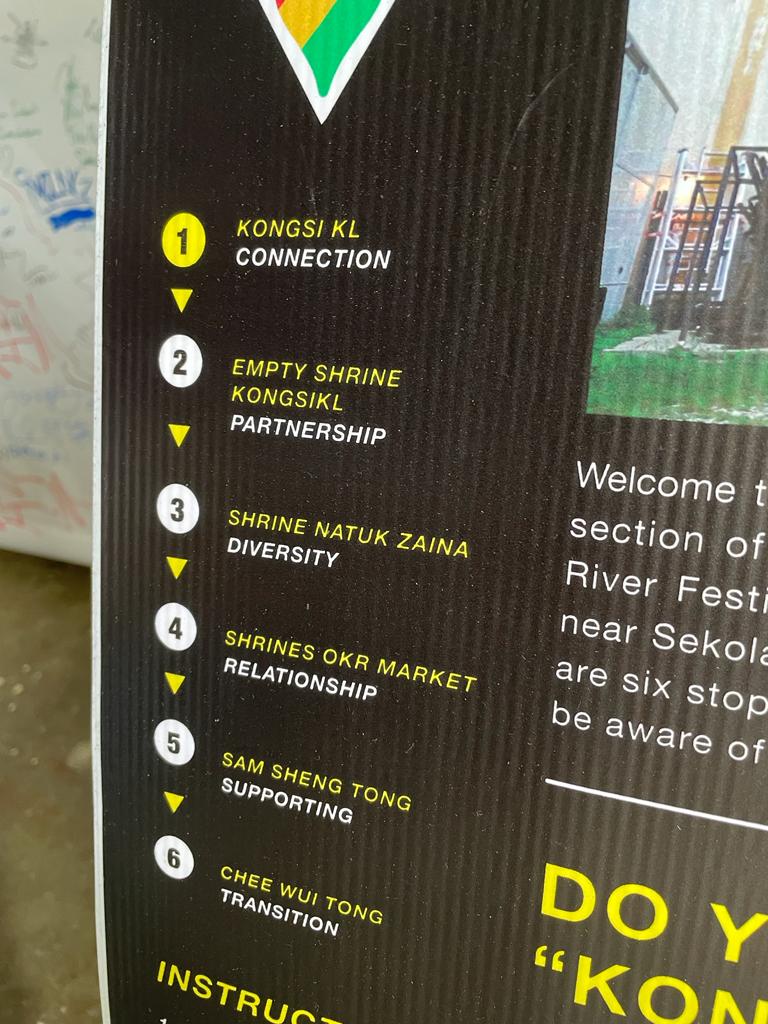

After the dialogue, we went in search of Datuk Kong ourselves. The self-guided walk Datuk Gi Mana? consisted of five different shrines located around Old Klang Road within walking distance of KongsiKL.

Old Klang Road is an old part of town. Being the first major road built in Kuala Lumpur, it has been inhabited by Chinese people since the early generations of Chinese immigrants in Malaya. As such, throughout the walk, we passed through multiple hubs of Chinese activity, such as hawker centres and wet markets where Datuk Kong sits side by side with Indian deities.

It was fun to spot the subtle differences that differentiated each shrine. One Datuk Kong had one foot stepping on a tiger, while another shrine had a rock beside the statue. The offerings were equally diverse, with a variety of soft drinks, sweets and biscuits. One even had a serving of what looked like chicken rendang with rice. With all that variety just within several minutes of walking distance between them, one has to wonder just how diverse the practice can truly be throughout the far reaches of the nation.

Attending the dialogue and walk truly was cause for reflection on the diversity within Malaysia. While we have been taught since childhood that Malaysia is a melting pot of cultures, Datuk Kong is one of the clearest examples of how the beliefs of different cultural groups can meld together to produce something truly unique to Malaysia. While the Klang River Festival has officially ended, you can still visit the five shrines yourself by looking them up on Google Maps. Each shrine has a QR code that you can scan to find out more about their backgrounds. See for yourself the diversity of Malaysia.

Visit the Klang River Festival’s website and Instagram page to learn more!

For more BASKL, check out the links below: