The spirit of a river courses through Jameson Yap's distinctive style of calligraphy, layers of meaning flowing through the artwork.

By CHIN JIAN WEI

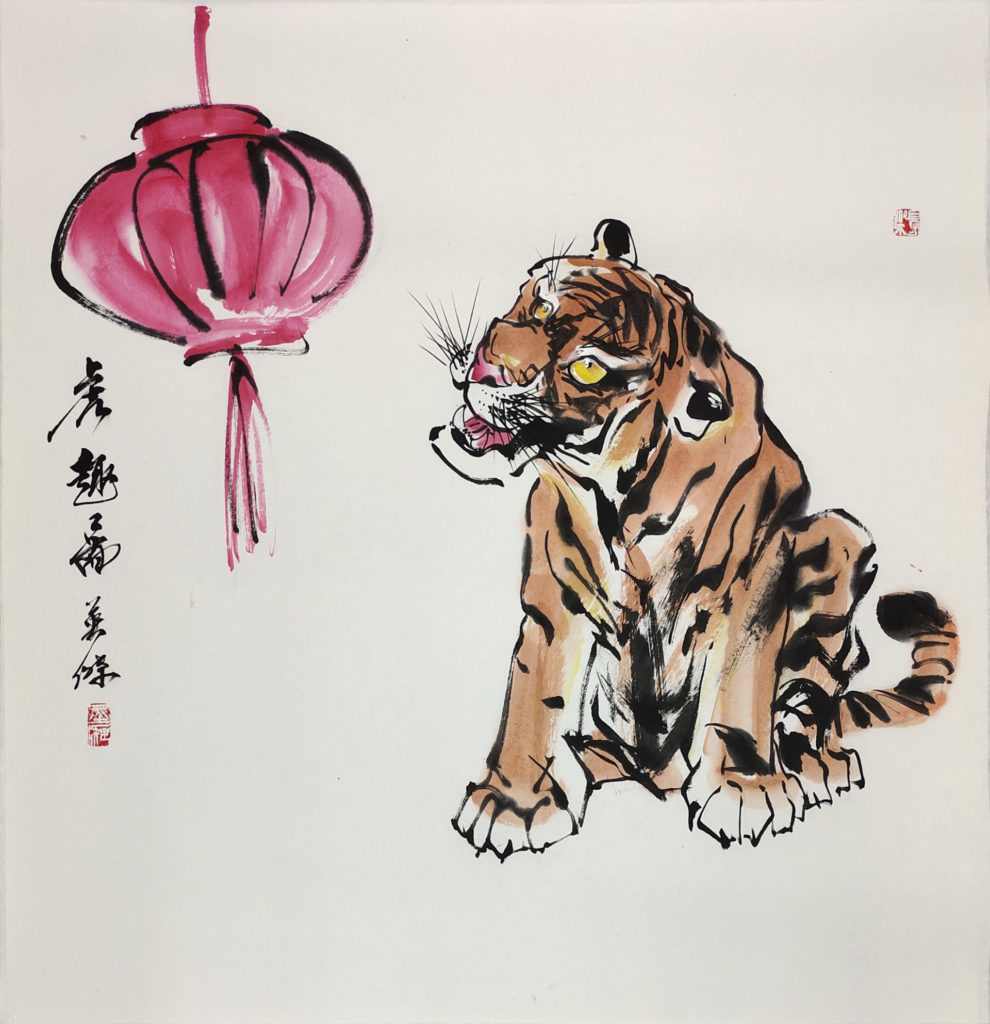

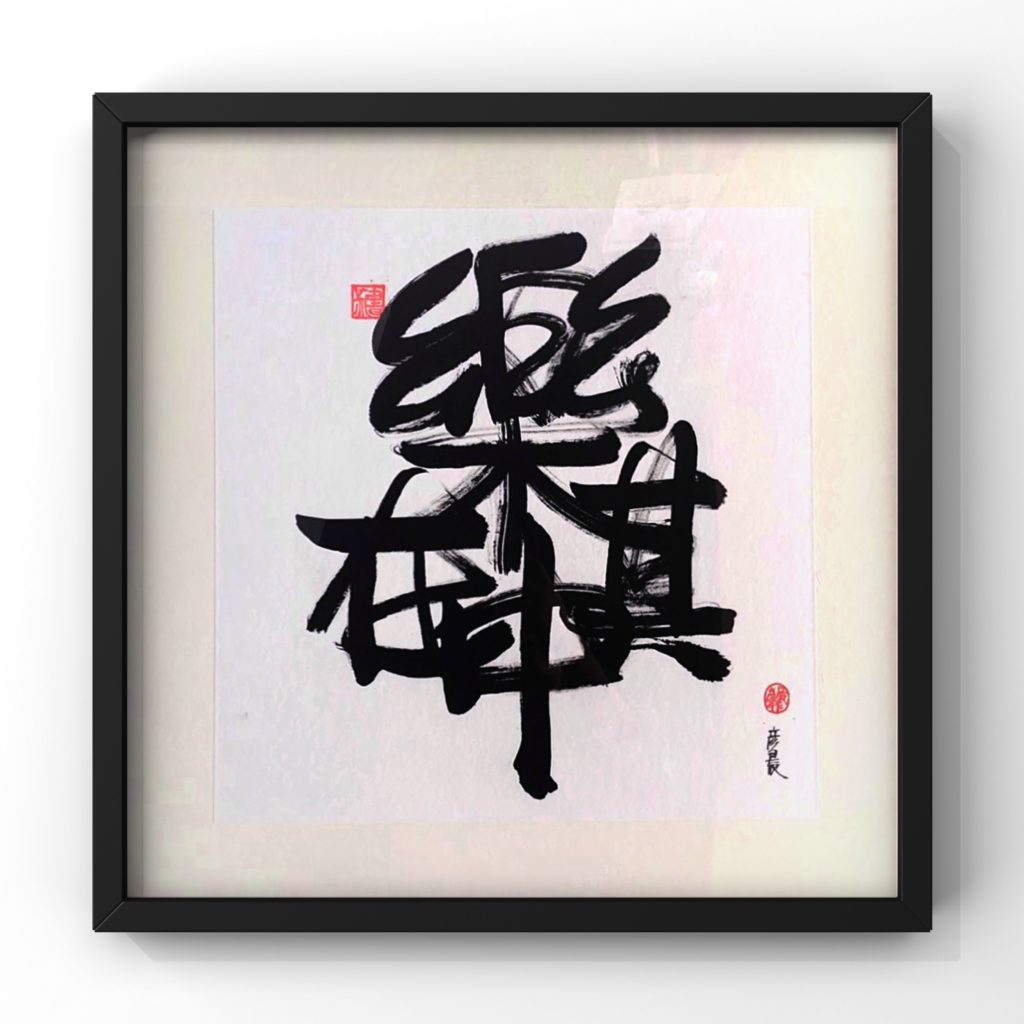

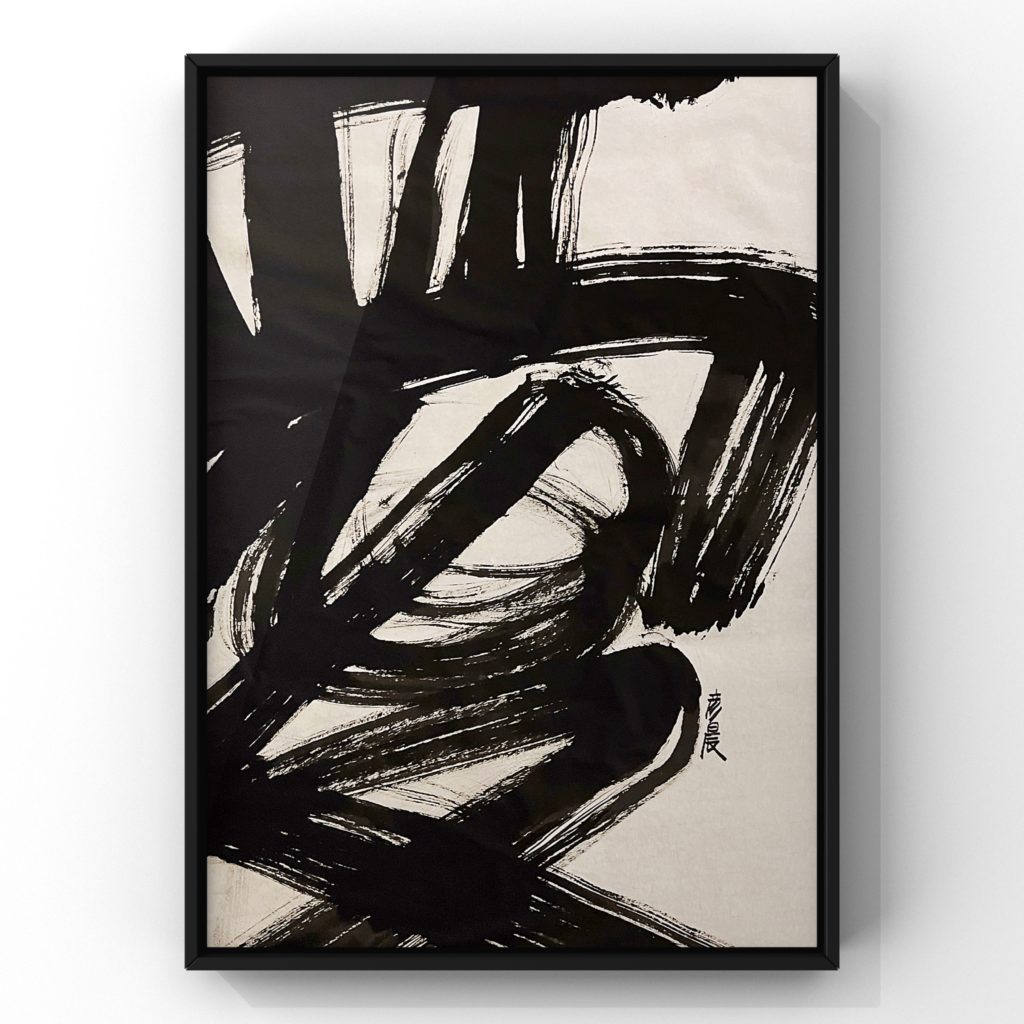

“The River Stroke is my signature,” Jameson Yap says of his unique form of calligraphy, gesturing towards one of the artworks on display. The Chinese characters flow into and over one another like swirling sand in a riverbed. “You will see characters overlapping one another, so every time you revisit it you will see different characters. You can appreciate it as abstract art, but if you go closer you might find a different meaning.”

Each of the artworks done in this style is dense and multi-layered, with half-hidden messages. You can choose to observe the individual characters or the gestalt, just like how a school of fish can be perceived differently depending on whether you are looking at an individual fish, or the entire school swimming in unison. Such are the artworks displayed in Yap’s first solo exhibition, From Theart.

In traditional Chinese calligraphy, the characters are not supposed to overlap. To the masters of old, Yap’s River Stroke would be seen as transgressive. Yap was classically trained from a very young age by his grandfather, an immigrant from China. “Ten years ago he passed,” Yap says somberly. “After that I started to be more daring in terms of calligraphy. I thought that if I wanted to bring Chinese calligraphy to the world, I would have to make a breakthrough. I took a while and I came up with my signature River Stroke, being more focused on being honest to one’s self instead of being constrained by all the rules of Chinese calligraphy.”

Yap’s work triggers instinctive responses from viewers. A piece depicting the Chinese character for dance, seems to almost spin before one’s eyes, the hem of the character twirling like a ballerina’s skirt. Another piece, seeking to depict coldness has ink blots bringing to mind a harsh snowstorm. “Some of my collectors will feel the piece first,” Yap says. “If they like the form, then they will start to learn about the art. This is how my art can interact with the viewers.” The first impressions, while strong, do not encompass the totality of the art’s meaning. Reading and understanding the characters allows for a deeper understanding into the messages the artist is trying to convey.

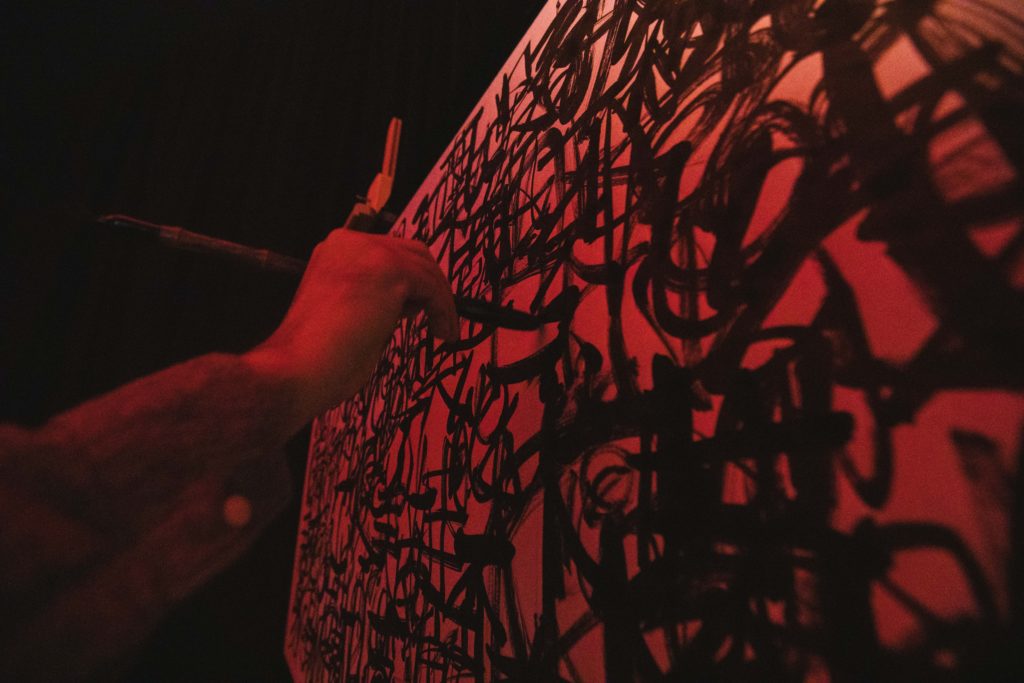

“First I have to enjoy the art myself, be confident of the message I want to deliver, only then will the art be able to influence others,” Yap says. “It can take less than a minute to complete one piece, but actually it takes a long time before that to prepare. It’s one stroke, I can’t plan along the way, I can’t have doubts, it has to flow naturally. You have to be sure and have control. For the piece depicting dance, I watched a lot of videos and studied dance. I needed a lot of research.

“The theme is from ‘the heart’,” Yap says. “All the pieces displayed here are somehow related to heart.” Yap indicates several of the displayed pieces conveying positive messages like freedom, belief in oneself, and getting one’s rhythm back. Yap is a big believer that whenever you do something, if you put your heart into it, it will lead you to the right path. “The reason I named it From Theart is because I think everyone should have a staunch heart. After the pandemic, now is the time to recover. You should be clearer on what you want from life, it’s time to listen to your heart and be honest to yourself.

“It has been a long journey,” Yap reminisces, thinking about his beginnings as an artist. “There was a lot of uncertainty until I started the River Stroke. It really made me confident that it was something I could show the world, to help reintroduce Chinese calligraphy to a wider audience. My journey isn’t that different from other artists, but I am lucky that I found my style, a style that is distinctive and obviously different from other calligraphy. That actually caught a lot of people’s attention. The first 30 years I spent practising before my grandfather passed, I sometimes used to think my work was a waste of time, constantly repeating the same thing. There were so many rules and I couldn’t break through. But to me now, I think that was super important as a foundation. You have to know something inside out before you can have a breakthrough. Just like Picasso,” Yap says, smiling. He is referring to how Picasso painted in a naturalistic style for many years before experimenting with more surreal and radical styles. Yap encourages other calligraphy artists to break the mould as well, after practising the foundations for a significant amount of time. “I think art should be like that,” Yap explains. “I think there’s only one place where laws don’t exist, and that’s the art world.”

Despite how the River Stroke breaks with calligraphy tradition, Yap is a purist in other ways. “Everything else is traditional. The paper that I use, the way I do the mounting and the type of ink I use. Until today I still insist on using mountain water to make the ink. I collect it when I go hiking. I think nature is so powerful, so I borrow some of its power and energy. Nature is what inspired the River Stroke. I was watching a documentary on rivers. There was a bird’s eye view shot of the Amazon river and it got me thinking. How can the river be so strong and yet flow so gently and flexibly? That gave me an inspiration: I should just go with the flow of my feelings. In a way, I think my grandfather would have been happy. He might go, ‘Oh you shouldn’t do this,’ but he would have appreciated that I’m introducing traditional art to many people.”

“Everyone thinks that you have to know Chinese, then only you are qualified to appreciate it,” Yap says, commenting on the perception that Chinese calligraphy is impenetrable to viewers who do not read Chinese. He encourages non-Chinese readers to treat his work much like abstract art. “More than half of my collectors are non-Chinese educated. You get attracted by the art form, you then go deeper and start to realise that each character also carries a lot of meaning behind them. Calligraphy is not just writing, it is art.”

For emerging artists looking to find their own style in the way Yap has, he offers up a few pieces of advice. “Look inwards instead of outwards. Many young artists would go outside to do research and end up confused. They take a bit from here and there, then in the end, how can you call it original? Sometimes, fast is slow and slow is fast. Sometimes when you try to do something fast, it goes nowhere. You have to slow down and understand yourself. Small steps at a time.

From Theart is held until Oct 30, 2022 at Lot 2.89.00, Level 2 Orange Zone, Tsutaya Books, Pavilion Bukit Jalil, from 10am to 10pm daily; There will be a book signing and meet-and-greet session with the artist on Oct 29. Check out Yap’s website and Instagram page to see more of his art!

For more of BASKL’s stories, check out the links below: