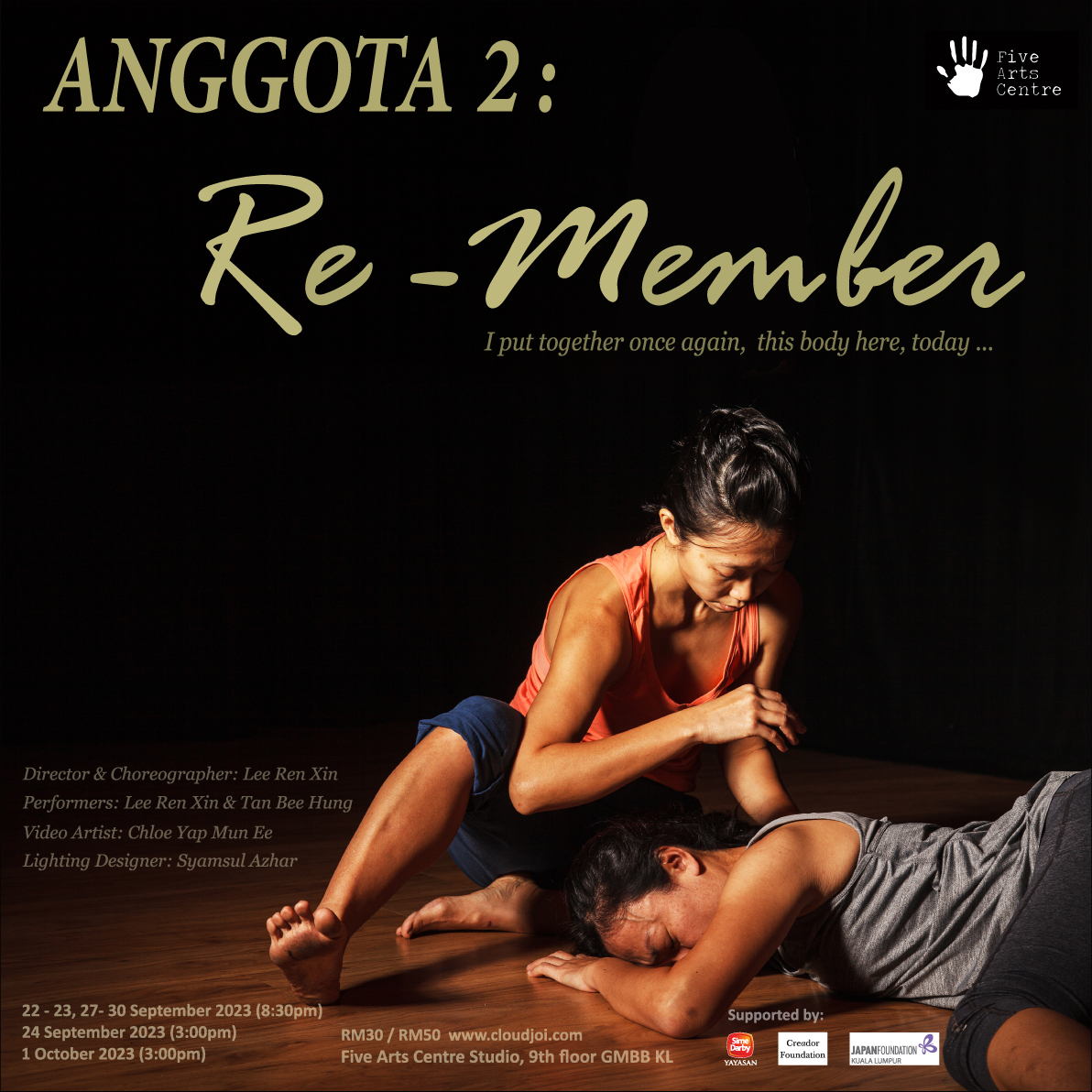

Choreographer-performers Lee Ren Xin and Tan Bee Hung take us on their second feels trip with the follow-up of ‘Anggota’ (2022).

By NABILA AZLAN

A couple of minutes into Anggota 2: Re-Member, we are welcomed by Lee Ren Xin (director-choregrapher-performer) and Tan Bee Hung (performer)’s low hums and slow-risen breaths. As their base-volume chants began to complement each other, their voices grow louder, faster, breaking the proverbial ice. As their screams pierce through, the cries slow gradually and after they have resettled on to humming, they stop, and like clockwork, they chugged on to their water bottles.

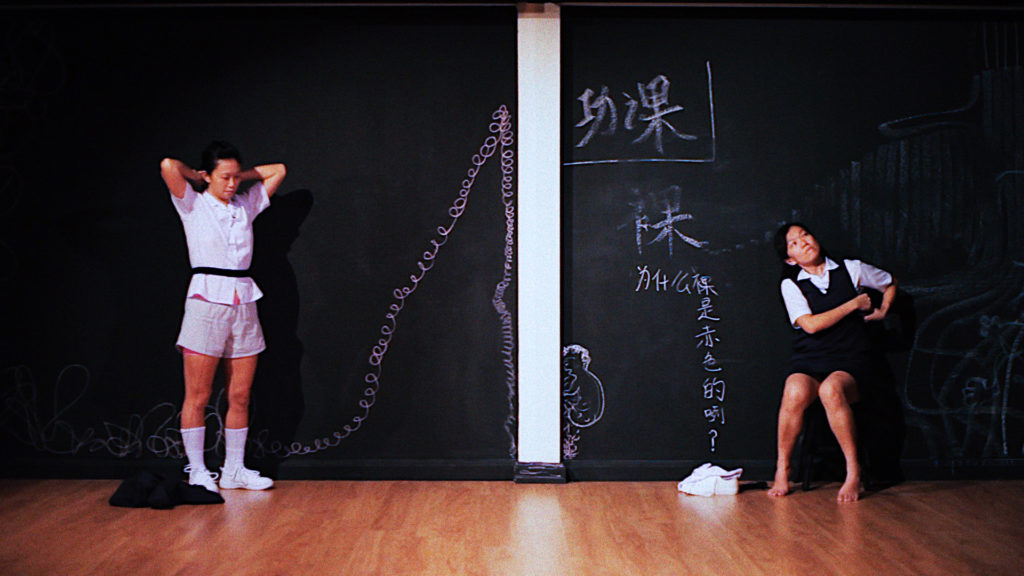

Slipping back into their navy pinafores turned inside-out for, Lee and Tan recall the story of their school days, plus what goes on in the aftermath – and invited the entire circle of audience to reminisce with. In case you missed it, Anggota is the recipient for two 2023 BOH Cameronian Arts Awards (Best Group Performance and Best Choreographer in a Feature Length Work)!

Similar to its first edition, Anggota, which I sat down for in 2022, Anggota 2: Re-Member is an intimate 360-view show, which means the audience (about 30 of us) sat cross-legged on Five Arts Centre’s wooden floor for roughly 80 minutes, with no intermission. This contemporary dance number continues to address themes like femininity and the keeping of memories, shining light upon a complex adolescence (fathoming a life they have lived then, now) while still-exploring the dynamics of a familial relationship.

I feel as though Anggota is mainly driven by a series of collected self-notes (‘self’ here being the choreographer-performers Lee and Tan), while Number Two intentionally expands the collection with a view of the inner workings of society.

Born Malaysian Chinese, performers Lee and Tan tell their own stories with the bending of their whole body and are now guiding others on how to tell their own stories (with the power of their respective limbs). The performers paint imageries of living life around decades-old taboo (“In my culture there is a lot of shame in shaking,” says Lee), later introducing us into the making of their choreographer selves (“I teach young bodies how to move / “I shape bodies of the younger generation”) while putting the two windows side-by-side.

Aided not only by physical accessories like chalk scribbles and water bottles (just like the ones we lug to primary school), Lee and Tan attempt to open a second discussion concerning how the past reaches out to the present by the means of feelings. This layered nuance is further supplied by the visual/audible accessories for the show – they are the recorded, frank self-interviews the choreographers give themselves and are played to match the dance sets in queue, which I find are great in framing the direction of the show. They also helped me, a person who would sometimes have trouble in reading between the lines, to better understand the contexts sewn into their crawls and twirls.

This play on depth and meaning is interesting, because every adolescent (my younger self was also watching the show with us) to a given level would find themselves at awe and at a loss at what they can do with their bodies. In one of the recordings, this was audible: “Do you feel that your body is not fully yours?” which is followed by “Do you remember your school anthem?” with no hiccup to spare.

Lee ponders upon her excavated feelings, of a younger her who once sang along to the school anthem. She mused at how her upbringing is filled with encouraging sayings; they exist not only in anthems but everyday idioms too. Relating to these on to a certain degree, I was understood that this is all too common for a child growing up Malaysian Chinese (fellow BASKL Writer, Jian Wei affirms this) – as the performer’s school anthem arises, its translations are presented to us. Not being able to speak a word in Mandarin, I stared at the lines “Revive our land” (Lee remarks, “I don’t know whose land, though!”) and then “Spread moral values” and “Be a tower of strength for others.” She posed this question: Why is there no picture of pleasure Chinese idioms? “It’s all about bitterness and how we are able to withstand them,” she adds.

The grown-up Lee and Tan are used to commanding body jiggles and unconstrained grunts by now as part of their practice, as they would conjure them during warm-ups. As choreographers, they have discovered how not being embarrassed about their bodies and simply moving to their rhythms releases unwanted pressure. (Jian Wei tells me that even the acts of shaking your legs while you are sitting is ammo to scolding one’s child. I laughed. To my “Why?” he says, “Parents say it is to not shake your luck away.”) Seeing how the activity is frowned upon growing up, the two, although sometimes pulled back by their culture’s teachings, strive towards letting go and listening more to their bodies. “I question why I am dancing,” Tan says. But finding little joys dancing has brought her, she adds, “I’m slowly learning to love myself. I doubt I loved myself when I was younger.” That felt warm. Says Lee, “My body my long-time guardian.”

I like the ways Lee and Tan cue us in to the other points of their lives which have delivered catharsis. They are in the littlest of things, like how Western pop music indirectly fuels this self-discovery (Parov Stelar’s All Night and The XX’s Intro are some) and the way the public displays of affection our closest ones, or lack thereof, would somehow affect us as adults (Lee says she once bombed her parents with “Why you no hold hands?”).

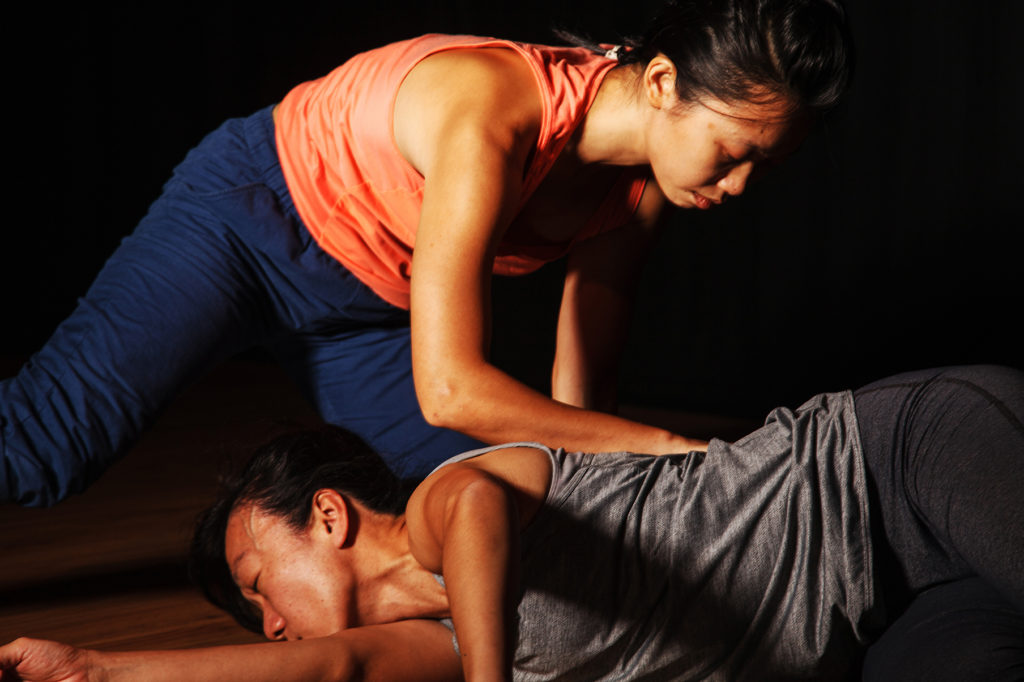

I love how, like maimed soldiers, the dancers every now and again would turn to each other as assurance – lifting and assuring themselves as not only a part of the show, but deeper, supporting each other quietly yet extensively through these shared experiences. Thank you, dancers, for sharing these with me.

Photos are taken by Chloe Yap Mun Ee, Prakash Daniel and Meshalini Muniandy; supplied by Five Arts Centre

Read more stories like this on BASKL via the links below: