Lesser-known chronicles of communism and the building of Malaysia call for the rewriting of our Sejarah textbooks. Five Arts Centre’s 'A Notional History' gives its audience a lot to think about.

By NABILA AZLAN

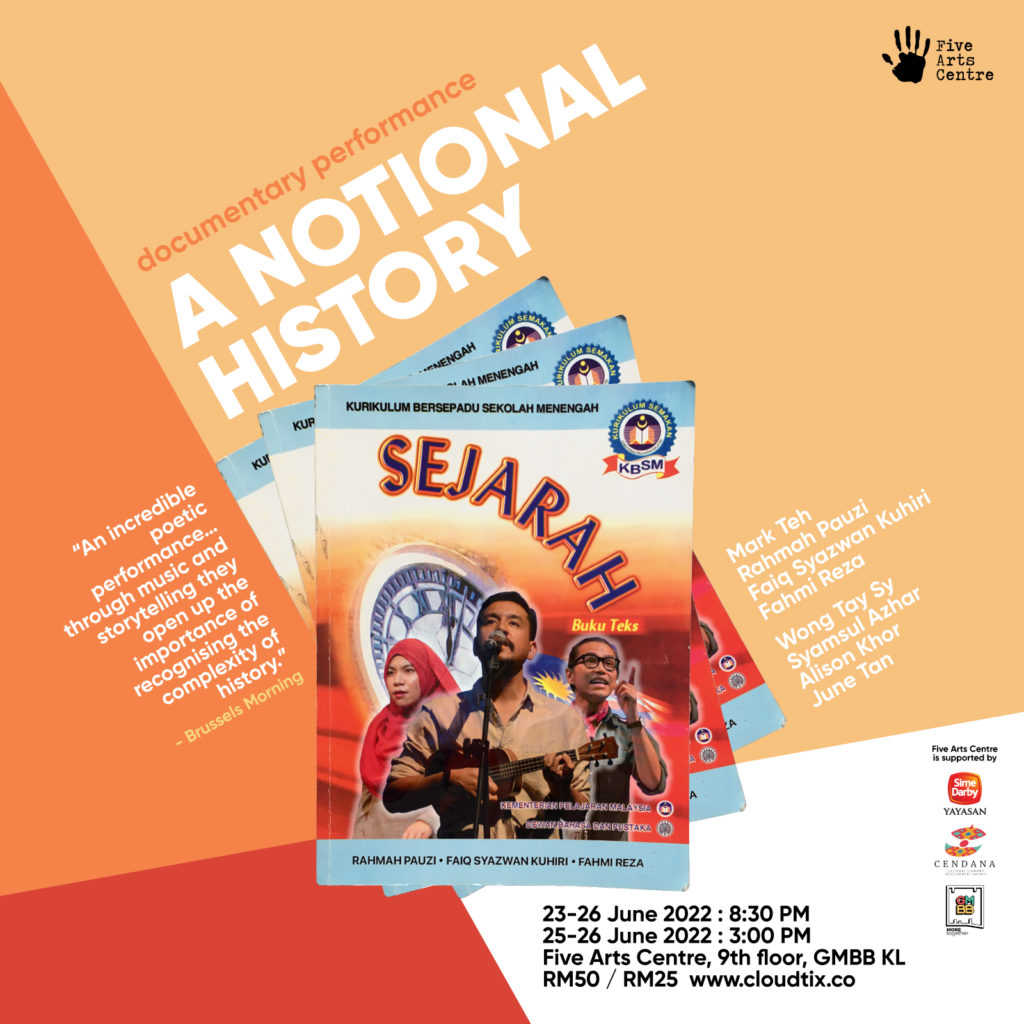

On June 24, 2022, I went to see Five Arts Centre’s critically-acclaimed documentary performance, A Notional History – semi-cold. Although I did not read any reviews prior to the showing, I did have a chat with the performing art centre’s coordinator/performance maker-researcher-curator Mark Teh to talk about its past and present offerings. Teh, who is also the director for A Notional History talked a little bit about the show’s debut in Japan, Indonesia and Belgium. Its four-day live showing in Five Arts’ new studio was the first time it was made available for those residing in Malaysia.

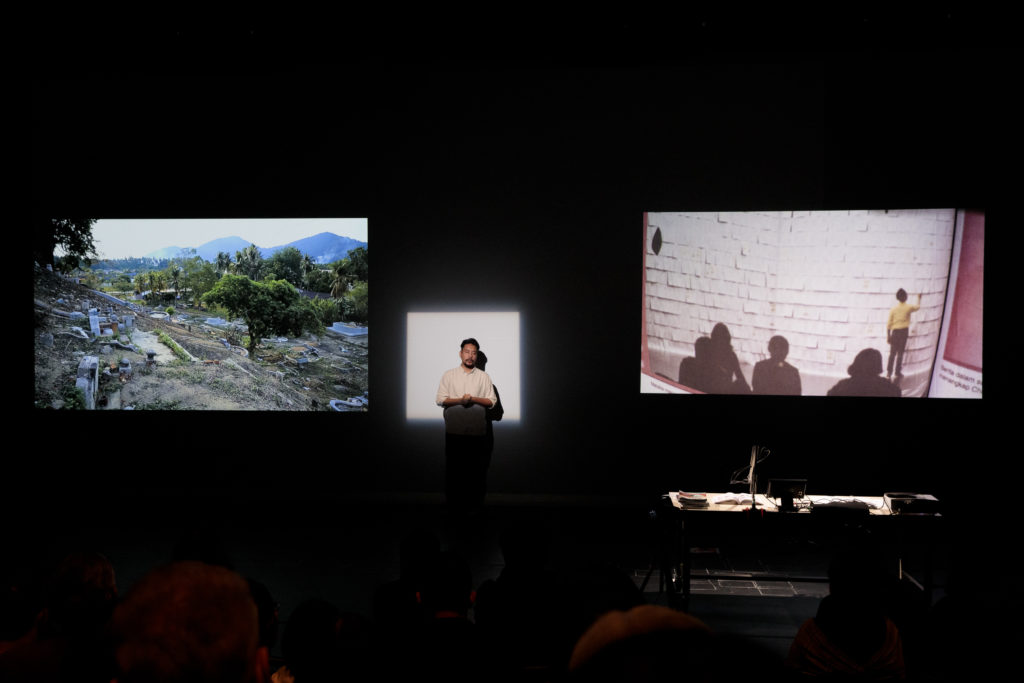

The show features three narratives; one from artist/BFM digital producer Faiq Syazwan Kuhiri, who is also in the Five Arts collective, plus two from social performers, journalist-filmmaker Rahmah Pauzi and graphic designer-activist Fahmi Reza. A Notional History in essence follows the Five Arts signature mold: Teh and the production team introduce non-performers Rahmah and Fahmi to deliver a truly Malaysian story, inviting the audience to mentally follow a discourse on New Malaysia (when Malaysians voted out the Barisan Nasional government after a 61-year rule) with layers of essential yet forgotten – or in a way concealed – documentation.

An activist, a journalist, and a performer excavate school textbooks, inherited memories, and video interviews of exiled revolutionaries – uncovering erasures, exclusions and questions around the Malayan Emergency. They investigate and speculate on the possible histories for a ‘New Malaysia’, intersecting the personal, the national, and the notional.

Five Arts Centre’s synopsis on A Notional History

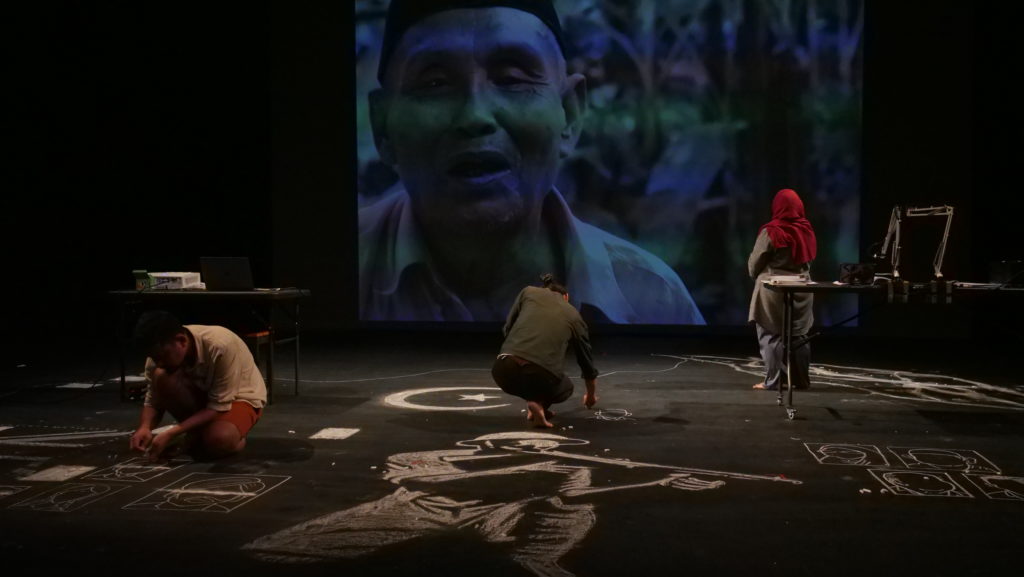

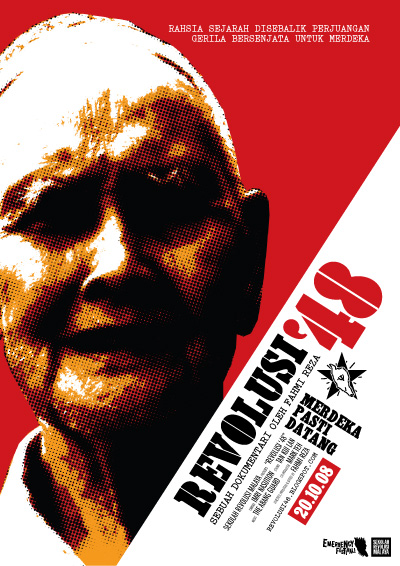

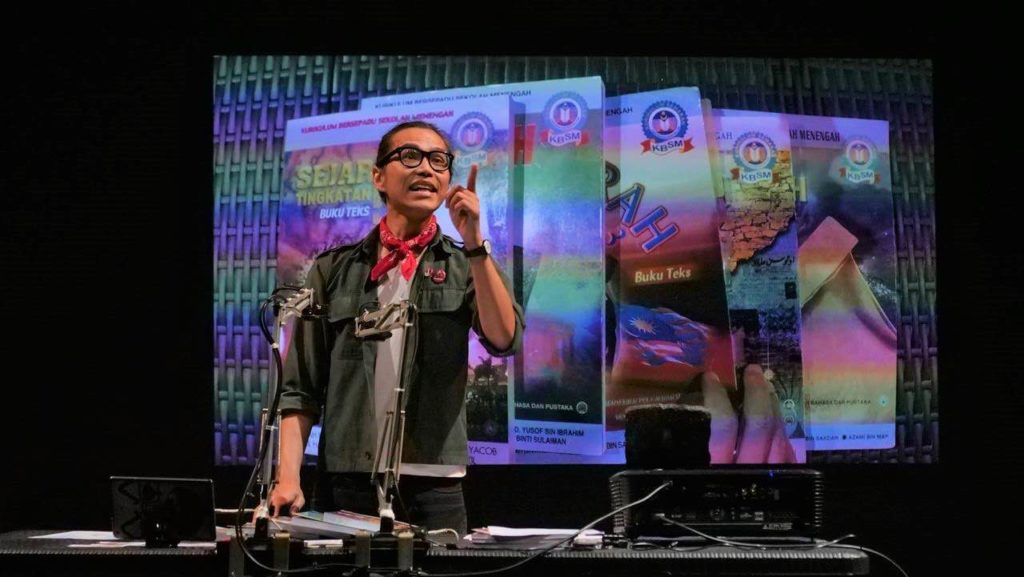

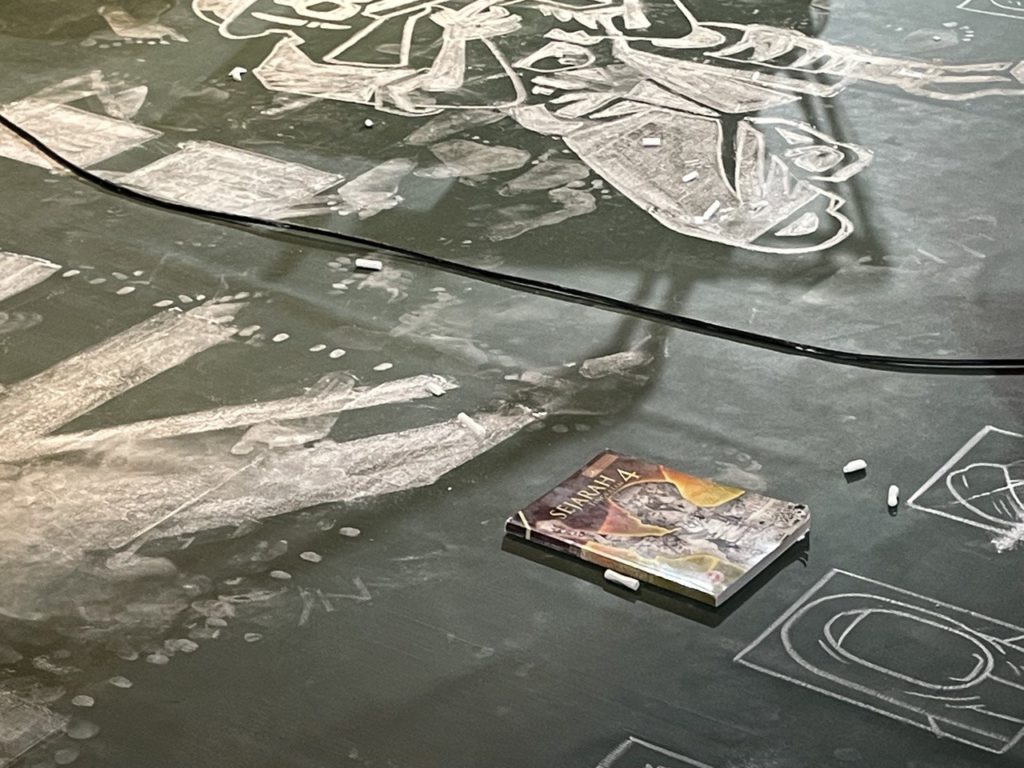

Running for 75 minutes with no intermission, the show relies on multiple tools – the verbal, physical and digital – to paint the story of how the political and notional past intertwines with the present. It opens with Faiq’s singing and ukulele playing, while Rahmah and Fahmi scribble away and make prints out of chalk stubs on the studio’s chalkboard floor. Presented in an English-Bahasa Melayu mix, all accompanying songs and further storytelling components are made to go seamlessly with selected clips from Fahmi’s unfinished documentary film, Revolusi ’48 (2008), which puts exiled Communist guerillas (associated with the Malayan Communist Party) onscreen to tell their part of the story on independence. Malaysian Sejarah or history textbooks for Form 1 through 5 are used to navigate the actors’ delivery throughout the show.

A Notional History is in line with both Teh and Fahmi’s past associated productions (Baling, Fragments of Tuah and 10 Tahun Sebelum Merdeka) which were also about historical presentation and representation. Questions like ‘Is this flow of documentation true?’ and ‘If it is, then is there anything else that we can take in consideration to make this story more whole?’ quickly become the prerequisites.

The unfinished Revolusi ’48 follows about a dozen elders – men and women who has fought as communists – each living in exile since the Malayan independence and formation of Malaysia. They have since found respite from their past lives in Southern Thai jungles, where the film crew documented their memories of the 12-year guerilla war and what they thought of their lives at the time the documentary was filmed; whether they missed home (they do) and whether they regretted their decisions of joining the communist movement (they do not). Why is the docu-film still unfinished to this day? Fahmi expresses his fear for safety; ever since the film, he has been called a communist over social media and received numerous verbal and non-verbal threats. “Mungkin aku takut (Maybe I’m scared),” he says.

Fahmi laments over how the Malaysian history textbooks put too much emphasis on some subjects and forfeit some others – the contributions of UMNO as the main force towards Malayan independence being the former and left-wing nationalists’ parties’ (like the Malayan Communist Party’s) role in it all. A short clip from the highly controversial panel presentation featuring lawyer-activist Fadiah Nadwa Fikri at the KL Selangor Chinese Assembly Hall (KLSCAH) in 2018, titled Should We Rewrite Our History Textbooks? becomes a fragment of his narrative in this show. The armchair historian shares his thoughts that the writing of history shouldn’t be one-sided.

Rahmah, who admits to meeting Fahmi during the KLSCAH presentation, recalls her own experience with people in exile. She, who has met and talked to Ukrainian soldiers with PTSD from war time, relates the feeling of being “a refugee in your own country” – a situation in which the communist fighters are in. Upon seeing Chin Peng in living colour, she says, “These were men and women who fought as communists, in contrary to people saying they are simply Chinese, homesick or angry.”

Faiq, who starred in Baling reminisces about moments with his late father, who was in the Navy reserve. Prior to the performing arts project, he admits to not knowing a lot about communists. Although, he remembers his father’s stories about the “ghosts and witches” who resided in the jungle – he even got the opportunity to record the then-65-year-man telling the tale.

While Faiq’s recordings of him were lost in time, he remembers a fraction of them, including one about the Communist Party of Malaya’s senior leader, Rashid Maidin. Says Faiq, “My father remembers him as unkillable figure, even a thousand bullets would miss him.” And like Fahmi and Rahmah, he shares the same curiosity about the guerillas – the shadows in between the trees – and how come they did not get their part of the war story told.

Poetic and thought-provoking, there are so many branches to go about in discussing one’s interpretation of the intention behind the show. Where do I stand in the inclusion of said “alternate narratives” in the rewriting of our national history? Does it even require a rewriting? One thing I’m sure of was how the show left me lost for words and hungry for more research and reading regarding the topic of the Malayan Emergency. While A Notional History might open a can of worms, I feel as though this should be shown more widely, to more Malaysians. Despite where one stands on the political spectrum, such curiosity (even if lace with a tinge of anger or confusion) may lead to an increase of round tables, instead of death threats.

Related readings: Mark Teh is reinterpreting history as we know it; Five Arts Centre maps out a new future

A Notional History was performed live on June 23 to 26 at Five Arts Centre’s studio in GMBB KL, and will be performed at Loft 29 in Penang at the George Town Festival on July 16 and 17, 2022. Tickets can be bought here. To know more about the show, go to the performing art centre’s Instagram or website.

Feature image is of Faiq Syazwan Kuhiri shot by Komunitas Salihara/Witjak Widhi