After the tireless trend of imitating Pop Surrealism and contemporary Realism, is the art trend shifting towards Minimalism?

By AMAR SHAHID SALEHUDIN for LENSA SENI

Back in the mid-2000s, among the issues discussed by the old guard of Malaysian art was: why did Op-Art fail? Optical art was a minimalist approach to visuals, with a focus on optical illusions as a form of serious art.

Much philosophical banter was expanded on discussing the genre’s demise. The obvious reason – but less discussed – was how the prevalence of vector and bitmap-based digital software was becoming more accessible, rendering traditional methods obsolete.

Vector images were becoming ubiquitous, and thus the hard-edged paintings were losing its gimmick at the physical space. It was a simple question of technique – the improvement of methods had simply overtaken the novelty factor.

Op-Art and minimalism had their stint in the 1970s and 80s era of Malaysian Art. The 1990s gave way to the figurative trends of Matahati, though abstraction remains in the bastions of abstract expressionism, through the works of artists such as Awang Damit and Yusof Ghani. Figuration and Pop-surrealism remain as the main strong trends today, ceasing to show any signs of wane.

I have been using the word “trend”, a somewhat derogatory word to describe the High Arts. Yet it is what it is.

This is the first word that came to mind after seeing the MEAA 2019 Winners Showcase. MEAA2019 Winners showcase was a recent exhibition held to celebrate the winners of Malaysian Emerging Artists Award (MEAA) 2019. The winners were sponsored a trip to the Philippines and expected to produce a showcase of works inspired by their trip. Due to the pandemic, the showcase was postponed to 2021. Such regular award shows also serve as a watermark for recent trends and innovations in Malaysian Art, hence the expression.

The word “trend” describes both the negative and positive sides of the meaning. In particular, the works of Syed Fakaruddin, Fazrin Abdul Rahman and Saiful Razman signal the rise of minimalist-oriented visuals in recent Malaysian art. This new resurgence surfaced not due to new adventures in aesthetic ideology, but rather a renewed interest in surface mark making that branded and repackaged itself in a minimalist fashion.

Simple, deconstructed visuals were preferred. In these works, paintings are treated as paintings. Mark-making is celebrated here, instead of fruitlessly trying to grasp historical relevance in describing the origin of one’s visuals.

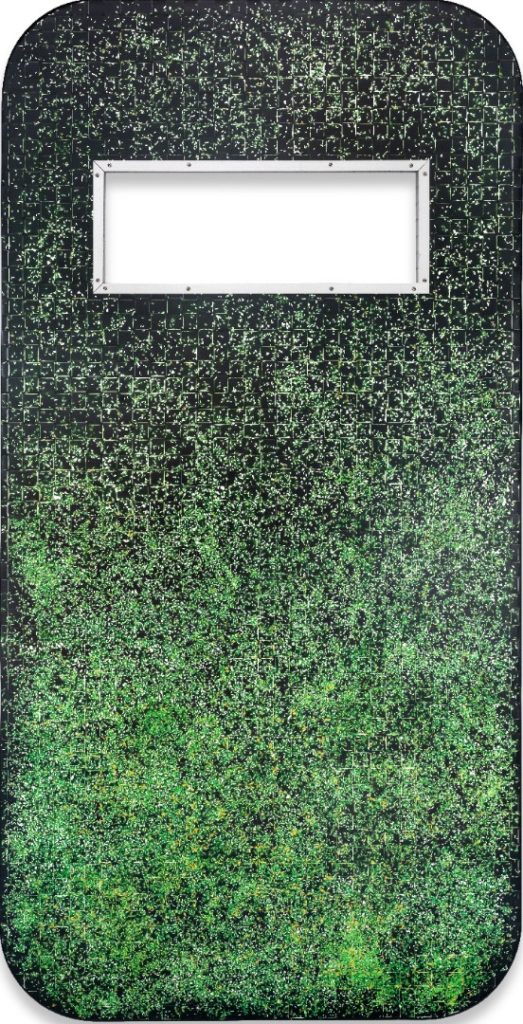

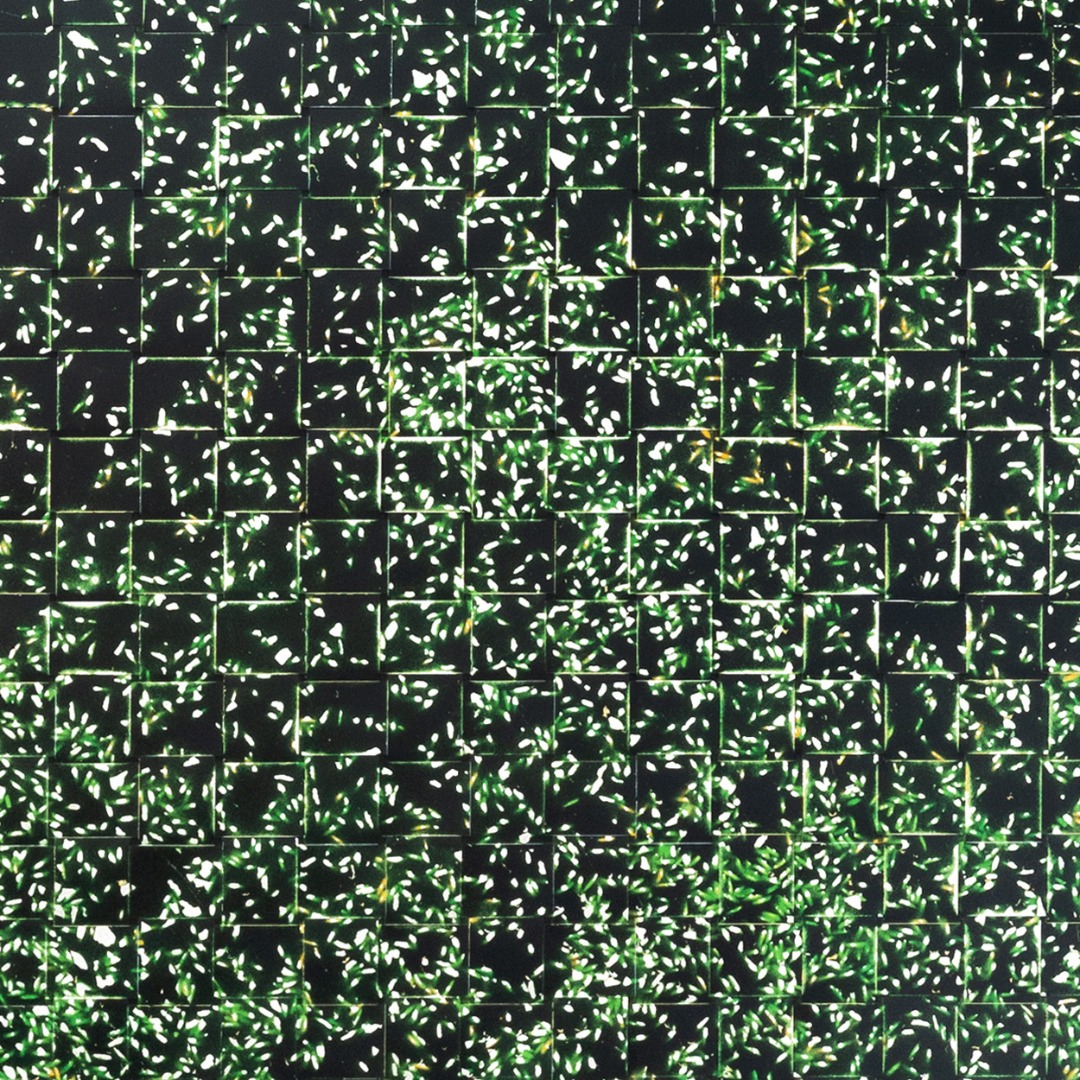

Experiential though it may be, it doesn’t mean that the works cease to be commentative. Fazrin’s police riot shield with rice marks is a great example. Marks created by masking paint with rice grains over a riot shield-shaped surface serve as a subtle but insightful commentary – about the struggle of local Philippine farmers with the authorities, inspired by the MEA Winners’ trip to said country.

This form of subtle commentary serves as a valuable tool of breakthrough in injecting social commentary suited to a Malaysian climate. It respects the need for institutional censorship, but at the same time it allows an entry point into deeper issues, should the audience decide to learn more. The execution in minimalist form is the best execution possible, with no frills such as needless pop-surrealist mascots to describe injustice or any other form of angst. The message is simple and precise.

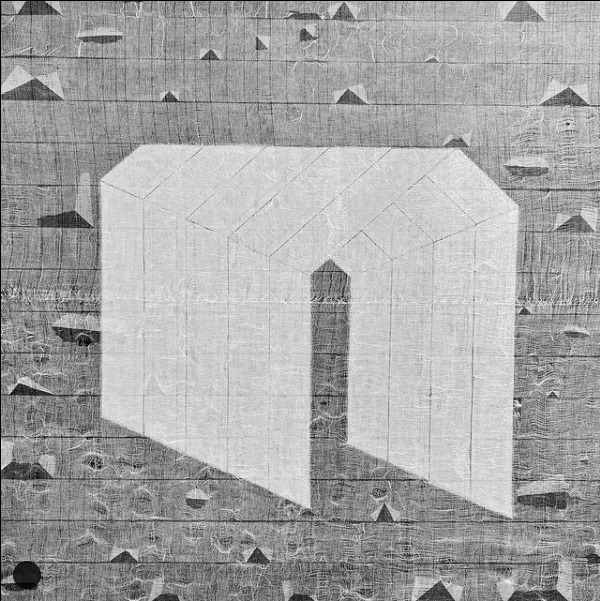

A perfect segue into Fazrin’s work would be Saiful Razman’s. Saiful’s work is already well known for its quiet monoliths of gauze and tissue on canvas. His recent work that was crowned as UOB’s Malaysian Painting of the Year coincides greatly with the MEA2019 works. The commentaries lie not on the immediate visuals, but rather on the use of materials.

Medical accoutrements such as gauze were a stand-in for his experience of the pandemic. This reliance on monolithic, minimalist visuals is once again a proven effective method in describing a particular issue. After being bombarded by heavy visuals and grotesque pop-surrealist characters in the more populist works in the scene, such a method serves as a very welcome breath of fresh air.

Syed Fakaruddin’s works could be said to be the least minimalist of the trio. Yet, they still employ simplification of visuals as their aesthetic strategy. Artists such as Awang Damit serves as a great example, as mentioned earlier in the essay. Syed is very much a loyalist to Awang Damit’s school of abstraction, as can be seen from his 2019 submission to Bakat Muda Sezaman (Young Contemporaries) in the National Art Gallery in which he covered a minor original artwork, courtesy of Awang Damit himself, with a frosted acrylic panel.

The work took on an even further abstracted approach. Syed’s work is interesting in the sense that the marks of figuration towards abstraction could still be seen, but now in a more graphically constructed space – particularly with his recent fondness for shaped canvasses and literal captions.

I would not seek to encourage any audience to discard fun for philosophical ultimatums. There is nothing wrong in interpreting visual trends as fashion. It might be a weak argument for aesthetic excellence, but it is a valid one, nonetheless. There is also nothing wrong in appreciating a particular work for its mark making alone. If anything, such enjoyment of detail may serve as a great reason for an audience to once again enjoy art in its original live setting, rather than through their screens. If captivating enough, the work might hook a few audiences into further understanding their intent.

A few other artists, beyond the trio discussed, show some promise. Artists such as Izzudin Basiron are consistent in producing minimalist deconstructive works, inspired by architectural forms. His works shows space and opportunity for commentaries, should the artist choose to be bolder.

Choo Ai Xin’s work which emphasizes concrete surfaces is another interesting take, away from traditional canvases, with an added conceptual twist. Her anxiety about the pandemic led to reproduction of red lines now ubiquitous on shop floors, used as a social distancing cue. These lines take on new contexts as she repurposed them to show the distance and emptiness in her paintings instead.

After Matahati-ism, Budinism and Didi-ism, will neo-minimalist works be the next to be widely emulated? Perhaps they will be. But the subtext to this essay would be: is Malaysian art in danger of being treated as fashion? With trends that keep recycling themselves?

I have no qualms about such a future. At least not yet. And we can revel in the comfort that in the next few years through the endemic phase, with artists eager to get out of their pandemic cages, audiences could be seeing some interesting moves in the scene.

Amar Shahid Salehudin is a participant in the CENDANA ARTS WRITING MASTERCLASS & MENTORSHIP PROGRAMME 2021

The views and opinions expressed in this article are strictly the author’s own and do not reflect those of CENDANA. CENDANA reserves the right to be excluded from any liabilities, losses, damages, defaults, and/or intellectual property infringements caused by the views and opinions expressed by the author in this article at all times, during or after publication, whether on this website or any other platforms hosted by CENDANA or if said opinions/views are republished on third-party platforms.