What does a man who is coming back to society after a decade of living in the wilderness and an astronomer just turned widow have in common?

Story by ATIKAH HANAFI | Photos by DEV LEE and MELISSA TEOH for Lensa Seni

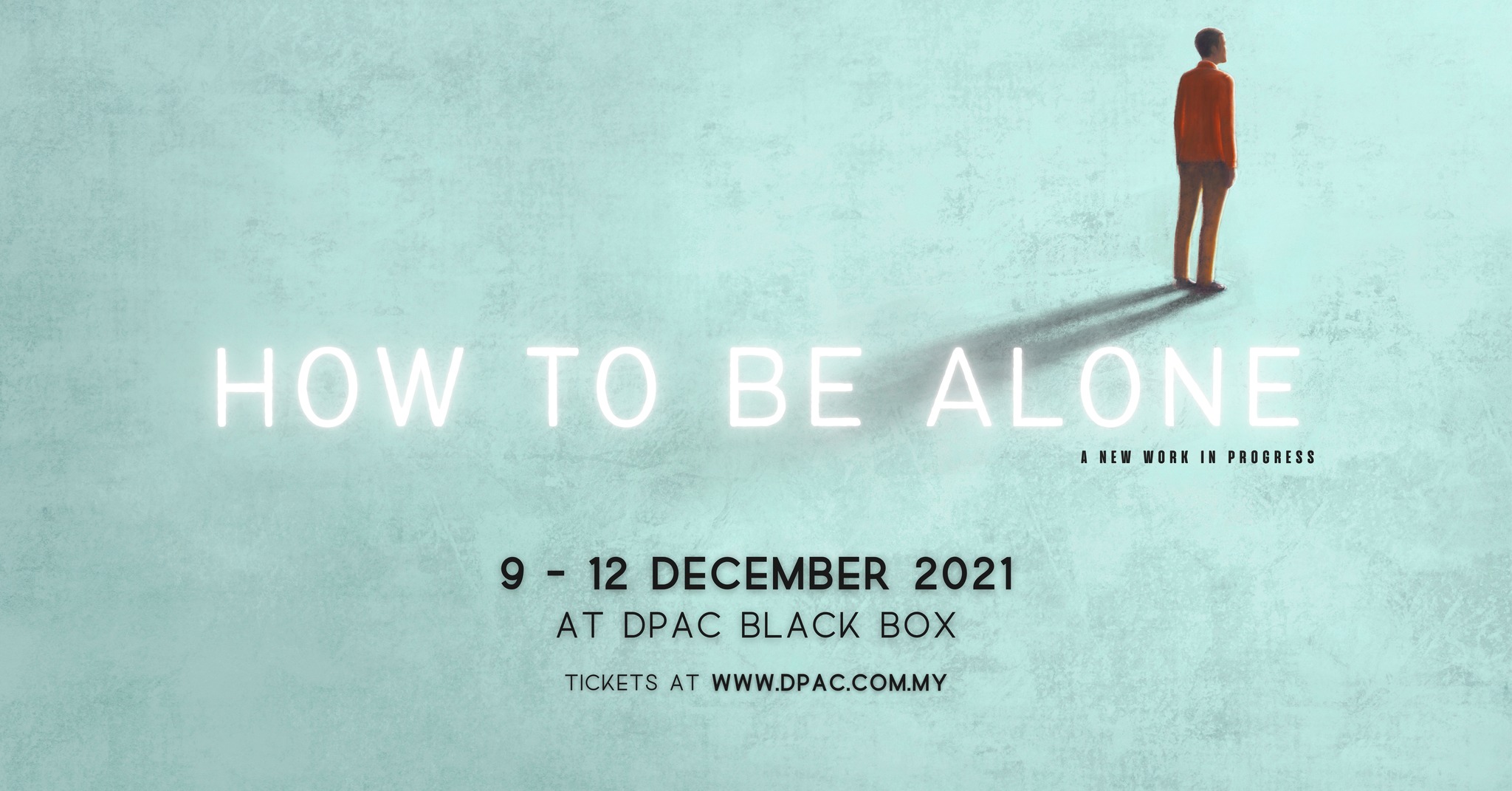

Solitude, loneliness and exile are themes that inspired the birth of How to be Alone, a workshop production sprouted from a series of conversations between a Malaysian director-actor Ghafir Akbar and a New York-based director and dramaturg, Joel Waage.

The script went over a 16-month development process that included inception, research, documentation and a completed workshop draft. Along the way, American actor Danny Jones joined in to include his point of view of the piece.

Contrary to the title, the show neither served as a plain instruction manual nor a didactic how-to on being alone, but rather an invitation for the audience to contemplate two parallel experiences of dealing with loneliness and being alone through the experiences of one Ashwini from Ipoh and William Hoff.

In Ashwini, we found a brilliant astronomer who, following the death of her husband, had to face the fearsome period of being alone once again. William, on the contrary, had to forgo the comfortable world of solitude that he was so familiar with as he returned to civilisation after 10 years of living alone in the woods.

How to be Alone brought the audience into a reflective journey as these two characters ruminated in the cosmic universe of aloneness.

Performed in Black Box at Damansara Performing Arts Center (DPAC) from Dec 9 to 12, How to be Alone featured a unique international theatre collaboration between freelance theatre artists across two separate geographical locations, Malaysia and the United States.

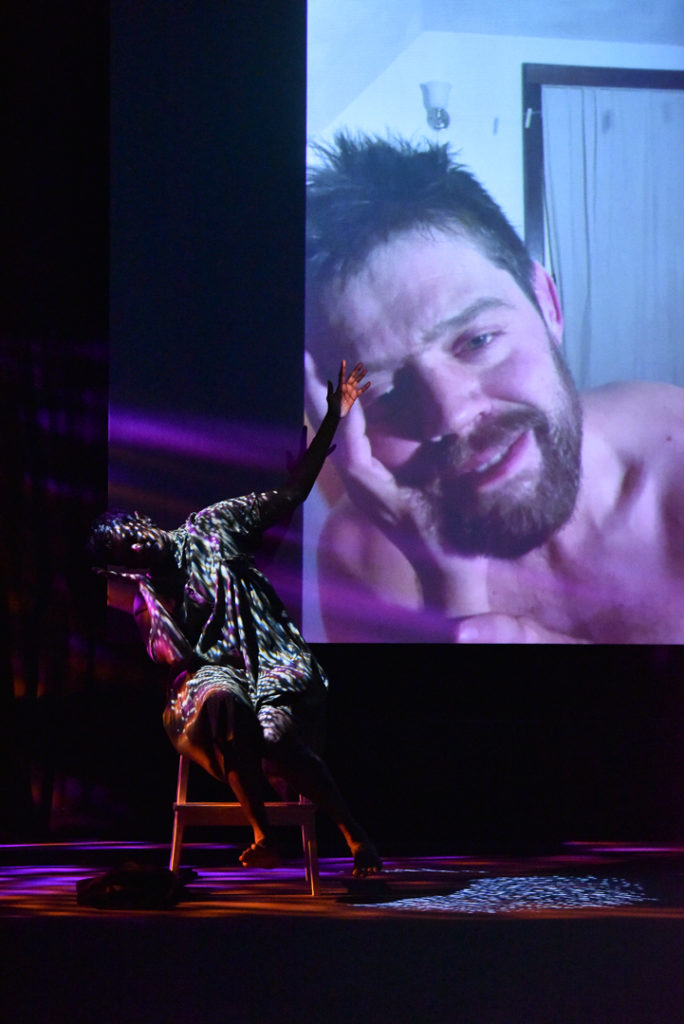

Malaysia’s award-winning actress Jo Kukathas returned to the theatrical sphere with a splendid performance as Ashwini. Working alongside her via a virtual performance was Jones who played William Hoff.

It is interesting to see how the play meshed Jo’s live performance in the theatre at DPAC with Danny’s virtual performance, streamed from his home in Wisconsin, US. Nevertheless, the two mediums worked well in highlighting the contrasting circumstances experienced by Ashwini and William.

Solitude and Loneliness as Convergence

The play, overall, gave an impression of a mixed media artwork that combined a collage oil painting, old newspapers, recyclable items and photographs to create a complete piece of art. It took inspiration from those who have found themselves in a solitary abyss, the play excavated found texts, existing literature, legends, interviews and new writing.

Ashwini’s lines included a quote from Gerard Manley Hopkin’s The Starlight Night, a reference to Julian of Norwich’s life and work, Revelations of Divine Love as well as a retelling of the Legend of Chang E and Hou Yi. As she reminisced on memories from her past, Ashwini dwelled on the astonishing wonder of the universe, the orbital movement of the celestial body, the mystery of the black hole and the enchanting eclipses.

At times, it might have been a bit difficult for the audience to follow as Ashwini intertwined scientific fact with her beautiful reflections of the cosmic world and her personal experience. However, Jo’s exceptional acting reverberated with the audience.

There were times when it felt as if she was speaking directly to you. As she fixed her gaze on the audience, the pain she felt in navigating the loss and grief of losing loved ones was amplified. Glassy eyes, tensed muscles and slightly shaken lips – even without words, her body language and facial expressions spoke for her.

William, on the other hand, reminded us of Henry David Thoreau’s words in Walden, especially in his absolute contentment on being alone in the wild. “I love to be alone,” wrote Thoreau in Walden. “I never found a companion that was so companionable as solitude.” His recount of nicknaming plants and describing their temperament like a mother would her children made some of us chuckle. It was something any plant parent could relate to.

Unfortunately, his years in the wild did not last, as frequent forest fires forced him to leave his haven. What remained was a video series called Hoff the Grid, where he shared his life in the wilderness with the online audience. However, the online community did not provide enough camaraderie to cure his longing to be back in the wild. William continued to struggle with the loneliness he felt after coming back into society. He then resorted to his phone, which he nicknamed Audrey, and began to disclose his struggles and concerns via video journals.

Another strong factor that propelled William to return to society was his encounter with a hospital nurse when he was saved from a fire. That simple act of human touch brought him a spark of electricity that ran through his body. This particular incident was an interesting point on which to ponder. As much as William was content with his life surrounded by forests, it only took a touch from another human being to make him realise what he had been missing all those years.

A lot more than just lighting

A big round of applause should also be given to the lighting designer, Ee Chee Wei. It is quite rare to see a play to put a heavy emphasis on the lighting design to achieve a greater effect.

The clever usage of different colours and hues added nuances to the atmosphere. More than just being aesthetically pleasing, the lighting was used brilliantly to serve an active role in adding more layers to the players’ existing emotions and moods.

There were many instances throughout the play during which the audience was left in awe at the cinematic effect that the lighting design brought to the set. There was one time when Ashwini was running on the same spot and the lighting was manipulated to create a motion-like effect to her movement.

The magical effect of the lighting was also felt when Ashwini was showered with layers of piercing light which created a smoke-like effect around her. At that moment, it looked as if Ashwini was an ethereal being and a shadowy figure as a part of her torso dissolved in the brilliance of the lights. It was indeed a breathtaking view that could only have been fully experienced by a live audience.

How to be Alone is considered a new work in progress. Since it is a workshop production, the play is expected to be refined further in the near future. Despite that, the production was impactful as it is. The scripts were rich with references to various literature and cosmic facts, rendering the more curious minds among the audience to pick up on reading and research.

Instead of providing us with answers on how to deal with loneliness and being alone, the play left the audience pondering on what our own take on solitude is. Indeed, How to be Alone was a much welcomed experience in the post-pandemic world.

Atikah Hanafi is a participant in the CENDANA ARTS WRITING MASTERCLASS & MENTORSHIP PROGRAMME 2021

The views and opinions expressed in this article are strictly the author’s own and do not reflect those of CENDANA. CENDANA reserves the right to be excluded from any liabilities, losses, damages, defaults, and/or intellectual property infringements caused by the views and opinions expressed by the author in this article at all times, during or after publication, whether on this website or any other platforms hosted by CENDANA or if said opinions/views are republished on third-party platforms.