Affected by a worrying slump in the art market, Malaysian artists adapted. Find out how.

By AMAR SHAHID/ANJANG AKUAN for Lensa Seni

Prior to the pandemic, Malaysian artists enjoyed patronage by collectors, and were able to command competitive prices for their art. In the fine arts sphere, artists could price their work on the higher side to focus on quality and limit production. This increased the scarcity of their works and encouraged collectors to be observant, and at the same time it allowed the artists a better working schedule. This was the “High Price, Low Volume” model of production.

Professional artists are always careful with their pricing. The speculation involved in pricing is like betting on the real estate market. Once the ceiling price goes up, it should not come down, as undervaluation will hurt all previous and future works. It is essentially a micro economy of its own, with potential for far-reaching mistakes, thus careful decision-making is required. Understandably, senior artists that have achieved high price ceilings are often reluctant to reduce their pricing, as it reflects on the value of their life’s work. At the same time, collectors are repelled by fickle and inconsistent pricing, because volatile numbers equals shaky investments.

Art is essentially a product of luxury. During an economic recession, art is usually the first industry to bear the blow. This is what happened at the peak of the pandemic. Works are currently no longer in high demand, to the point of a perceived impending collapse of the market. While there are stimulus packages, ultimately, artists and merchants have to adapt to the market and its current buying power. The demand is still there, it is just that people are unwilling, or unable, to pay a high price.

In order to pave the way towards recovery, the art market would need to focus on producing more works, but at a lower price point. Hence “High Volume, Low Price”.

Artists – particularly senior and established ones – might resist this, as it could hurt their artistic ego and mystique. It brings with it the “dirty” notion of, God forbid, merchandising. The dreaded state of “cheapening” one’s own art. Few are willing to admit that they are succumbing to market forces, and are obliged to lower their prices due to weak sales in tough times.

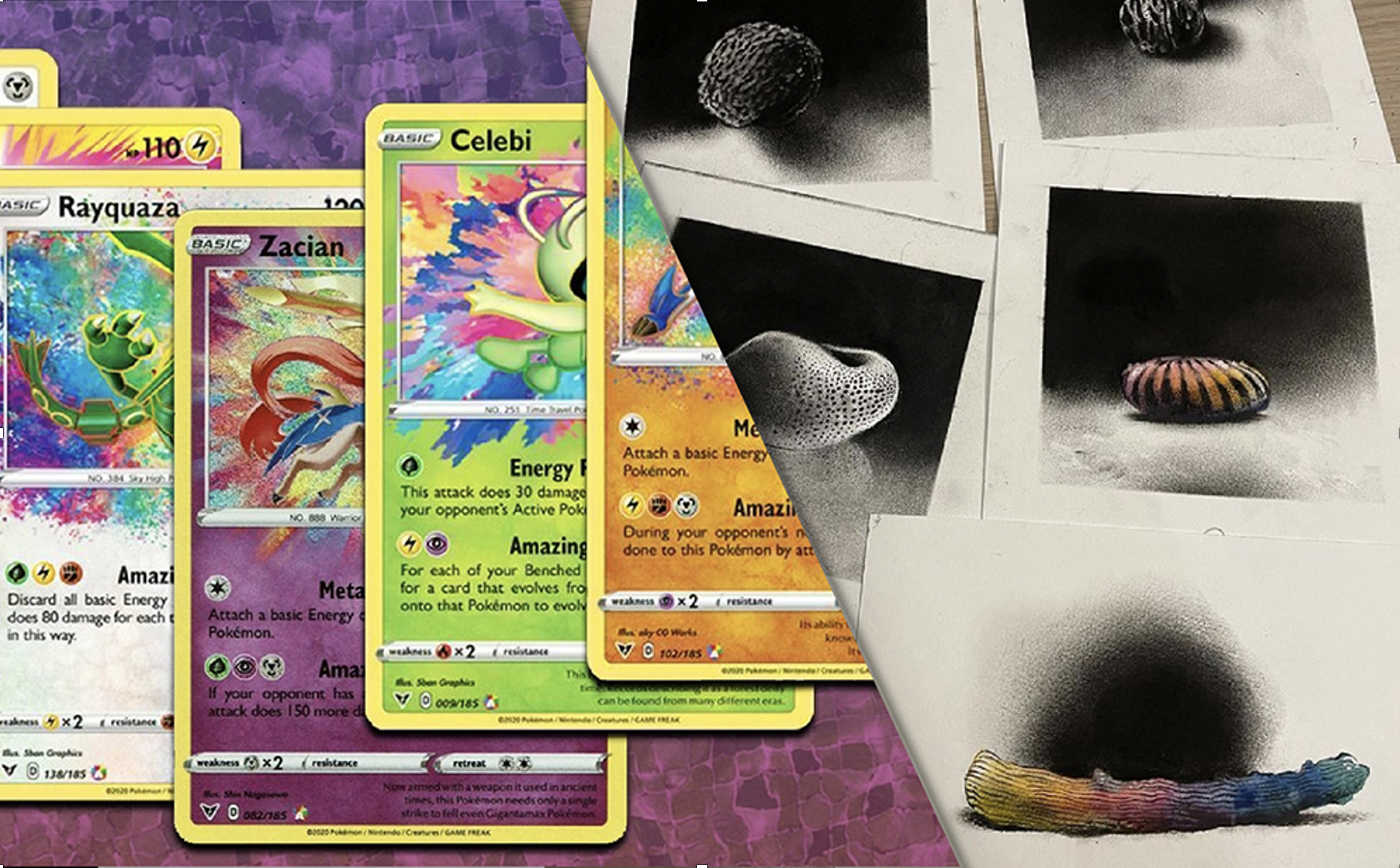

The trend of merchandising is nothing new, but is now gaining considerable traction, thanks to the combination of economic restrictions and the advent of new financial products. An often cited example is Japanese contemporary artist Takashi Murakami, whose style conveniently matches its merchandising opportunity. Another, more recent, example is Damien Hirst’s The Currency series. Hirst’s work is an interesting example, as it ties itself with the irrational nature of economics and the ecosystem. It claims to explore the very nature of collectibles and its legitimacy by way of limited editions and works made available as NFTs.

Despite its sophisticated claims, it is no doubt conforming to the model of “High Volume, Low Price”, in “bringing art to the masses”, whereas in marketing reality it is just tapping into the buying power of the larger demographic, rather than fishing for the patronisation of the elite few. However, for someone interested in economics and its behavioural theories, the series’ similarity to IPOs and Virtual Stock Markets – along with its potential disasters – is really intriguing. This is perhaps its artistic merit. The same can’t be said about the Malaysian art market.

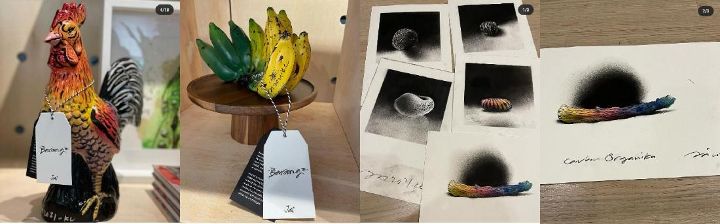

Diligent collectors might have sensed the pattern in Jalaini Abu Hassan’s most recent work, where he launched a line of small sculptures from his previous works, based on visual identity. Along with these collectibles (dubbed Barang2 Jai, or Jai’s stuff), he released a series of small charcoal drawings that eerily resemble trading cards. These items are marketed with magical words such as “notion of authorship” and “economic and social contexts” that gives them a mystical aura, further masking their kitschy purpose and strategic marketing.

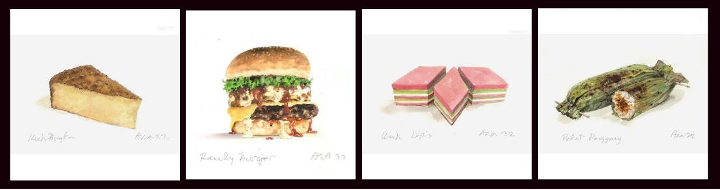

Seemingly in camaraderie, artist Ahmad Zakii Anwar also published (via social media) a series of small watercolour drawings of traditional Malaysian snacks. It is unclear whether these works are intended for sale or pleasure, although one cannot deny the series’ convenient timing.

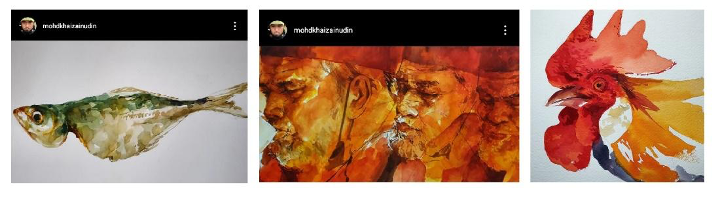

In a similar vein, fellow artist Khairudin Zainudin produced a series of small scale watercolours in numbers larger than usual. He confirmed the ease of sales for these items, and the convenience it greatly afforded him. He acknowledged the trend and has no qualms, so long as it allows movement and growth.

Positive side effects

With these works, we might finally be approaching equilibrium between merchandising, craftsmanship and high art. I was intrigued by the business model for Papu KL, a small gallery that focuses on affordable works by established artists. While it focuses on affordable pricings, the gallery also features high quality handmade craft items such as custom enamel buttons and other novelties. This further tightened the link between producers and art directors. I was intrigued by the possibility of commissioning craftsmen in producing works with provocative ideas.

The nature of the shift would also benefit previously neglected forms of art such as printmaking. This is the right time to introduce printmaking to the masses, as it is an affordable work with high discipline and manageable production. It should both scale and sell well.

There is nothing wrong with this model, so long as it is technically sound and accomplished, even on a smaller scale. Problems arise with works that lean heavily on their personal branding and persona, rather than technical accomplishment. Such work might benefit from a larger scale as it takes advantage of the size factor to deliver impact. However, these works that pack relatively few technical accomplishments per inch translate badly when the size is significantly reduced in order to generate a higher output. The works’ impact looks subdued and is often masked in the form of “simple enjoyments” and sketches or studies, despite their high volume and fast sales. This new model hurts loose draftsmanship, but for high draftsmanship work such as prints and etchings, it works well.

This is not all bad. It shows that the art market, as with other markets, is subject to adaptation if it wants to survive. The willingness to change, in itself, is a testament to the flexibility of the art scene in ensuring its survival. Like ripping off a Band-Aid, we just have to cast aside our egos and admit that, once in a while, we need to reassess our position.

Amar Shahid is a participant in the CENDANA ARTS WRITING MASTERCLASS & MENTORSHIP PROGRAMME 2021

The views and opinions expressed in this article are strictly the author’s own and do not reflect those of CENDANA. CENDANA reserves the right to be excluded from any liabilities, losses, damages, defaults, and/or intellectual property infringements caused by the views and opinions expressed by the author in this article at all times, during or after publication, whether on this website or any other platforms hosted by CENDANA or if said opinions/views are republished on third party platforms.