'Skola Gambar : Enrique de Malacca' at Ilham Gallery is an exhibition that combines history and fiction to tell the story of an unknown figure in our nation’s past.

By MURGAN GOVINDASAMY for LENSA SENI

History has predominantly been presented to most of us as a series of major events. A dozen battles fought here, a treaty signed there, a few natural disasters sprinkled in between and maybe a technological revolution or two wedged in just for good measure, all of which happened in a linear order, with each one progressively bringing us closer to the modern world that we live in. But living through economic and political crises, the pandemic and being on the brink of impending climate catastrophe, we can see that history and historical events are much more nuanced.

These days, historians get more excited about the more intricate details of history, often focusing on learning not through the lenses of Great Men, but those of the everyman. The challenge in documenting history this way is, of course, the lack of material to go by. As we all know, history is written by the victors, and they have rarely been of the peasantry.

It’s in this gap of data where Skola Gambar : Enrique de Malacca by Ahmad Fuad Osman operates. Bridging the gap between history, fiction and mystery through clever imagination, the exhibition at Ilham Gallery in Kuala Lumpur retells the story of a minor figure in our nation’s past who seemingly vanished from the annals of history into the vastness of eternity.

The story is of a Melaka native in the 16th century. Enrique De Malacca, also known as Datuk Laut Dalam, witnessed the fall of Melaka to the hands of the Portuguese and was taken captive, baptised and made a slave of Ferdinand Magellan. He would accompany Magellan on the famed Magellan Expedition – the first instance of humans circumnavigating the Earth. Enrique was said to have been very close to Magellan and was highly respected by the latter, having nursed him after becoming permanently lame from his injuries in the battle of Azemmour. He served as a translator, teaching Magellan about the Malay world. Upon Magellan’s death in the Battle of Mactan, Enrique was given his freedom, as per Magellan’s will. The historical account ends there, with no further trace of Enrique.

This exhibition sets out to flesh out the events surrounding Enrique’s life, humanising a figure who would otherwise have barely even been a name in a textbook, through a synergy between actual historical artefacts and pieces of original artwork. What stands out in this exhibition is while it’s presented like most history exhibitions, most of the individual artefacts are not accompanied by detailed descriptions. The viewer is left to wander through a collection of artefacts and artworks, divided into four chapters: Kacukan, Peta, Mare Liberum and Keramat. There is only a general commentary for each of these chapters, explaining the theme of the chapter in the context of Enrique’s life. This compromises the educational element of the exhibition, as the history enthusiast in me was left wanting to know more about the artefacts. However, walking through the whole exhibit, the intent is clear. The trade-off is better story-telling, while balancing the historical element. The viewer is made to use their imagination to see the world from Enrique’s perspective.

A bustling city, exotic aromas of spices from all corners of the world, disparate tongues spoken by diverse peoples, all set against the backdrop of the sea. This is the imagery created in one’s mind going through the exhibition and viewing the various artefacts. From small cannon to Chinese porcelain, and a few specimens of the Malay Keris, the exhibition gives a good idea of what the era was like.

As for the original art pieces, the portraits of the important characters in this story really stand out. It’s explained that the photorealistic portraits aren’t meant to function as photographs. The point is not to make the subject appear as they did in real life, but rather, as a crafted image. The backdrop of the painting is a location of importance, with the subject usually depicted holding some item that was associated with them. Bearing this in mind, I was better able to appreciate the portraits.

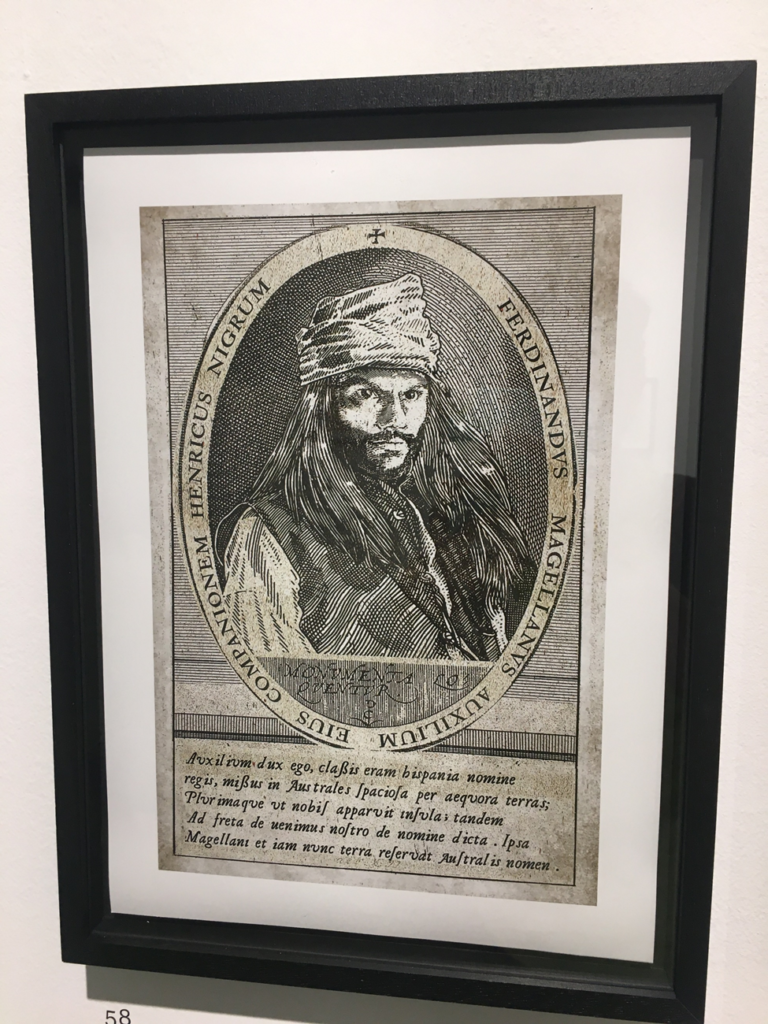

There were portraits of Magellan and Italian historian Antonio Pigafetta, which are replicas of existing paintings. Then there is Ahmad Fuad Osman’s UV print portrait of Enrique, depicting how the subject ought to be seen, or rather, how the Portuguese would have seen him.

What we see is a seafaring adventurous Malay hero, with his long, flowing, wavy hair and piercing dark eyes and a bandana wrapped around his head – almost a cross between M. Nasir’s Hang Tuah and Johnny Depp’s Jack Sparrow. Surrounding the portrait are the words Ferdinandus Magellanus Auxilium Eius Companionem Henricus Nigrum – Ferdinand Magellan’s helper, Enrique the Black. The portrait gives a good idea of how colonists would have seen Enrique – this exotic, brave, man from a distant land who was a loyal companion to Magellan.

The exhibition uses the story of Enrique to delve into the roots of Malay identity and the nature of decolonisation. Enrique is commonly believed to be a Melaka native, but there are other sources that attribute his origins to Sumatra. The colonial overlords did not really understand the racial complexities of the region, so his origins are even more unclear. He has even been classified as a mulatto.

There is much to be said about the cosmopolitan origins of Malay identity, and that is expressed well in this exhibition. Here, Enrique is depicted as a son of the Nusantara, his exact origins unknown, but he aids the explorers in understanding the culture of the region as a whole. He lived at a time when the major cultural hallmarks of the Malay people, such as Islam, the Jawi script, and court traditions began to crystallise. He lived through the transition from the traditional feudal power structures of Melaka, with its power based on trade and diplomacy, to a colonial one built on firepower and focused on the control of trade.

The ultimate point of the exhibition is for us to view our past from a different perspective, and not only in today’s terms. Enrique’s story is a powerful one, but not necessarily for the reasons we might expect. In the past, Enrique’s story has been retold as that of a traditional Malay warrior-hero, traveling the high seas and going on wild adventures. But through this exhibition, we are implored to look at his story and see all the reasons why he is not that hero, although still someone of great importance. He was an average person, not of noble birth. He was a Christian and a slave. His tale demonstrates the unforgiving cruelty of fate, his life turned upside down by the invasion of his city. However, it also shows the power of the human spirit.

Magellan may have “owned” Enrique, and he may have monuments dedicated to him, but he never actually completed his grand expedition. He died in the Battle of Mactan, in modern-day Philippines. Enrique’s story ends there, too. However, it is said that he was unharmed in battle, and that he could communicate with the locals. With those two facts, it’s not too far-fetched to assume Enrique could have found his way home from there, to a different Melaka. If this were true, it is entirely possible for Enrique De Malacca, a 16th-century Malay slave of unknown origin, with no known birth name, to be the first person to ever circumnavigate the Earth.

This exhibition shows us that with art, we can redefine how we see ourselves and our history. With just a little imagination and some creative curating, this exhibition brings to life the story of a person who was but a footnote. In doing so, it explores heavy themes such as decolonisation, nationalism, and fate. As we ourselves live through major historical events, it is nice to know that the little guy – the people like Enrique – have an equally compelling story worth telling. It gives a sense of significance in a hectic world where we are but twigs on an ocean where the tides are ever changing.

SKOLA GAMBAR: Enrique de Malacca is on at Ilham Gallery until May 15, 2022.

Murgan Govindasamy is a participant in the CENDANA ARTS WRITING MASTERCLASS & MENTORSHIP PROGRAMME 2021

The views and opinions expressed in this article are strictly the author’s own and do not reflect those of CENDANA. CENDANA reserves the right to be excluded from any liabilities, losses, damages, defaults, and/or intellectual property infringements caused by the views and opinions expressed by the author in this article at all times, during or after publication, whether on this website or any other platforms hosted by CENDANA or if said opinions/views are republished on third party platforms.