Meat on the Chopping Block explores the segmentation of the corporeal form and vulnerability in the face of the pandemic.

By CLARISSA LIM KYE LEE for Lensa Seni

A common sight in South-East Asia is a crowded pasar pagi or morning market. Shuffling bodies intersect with sprays of blood, dead animal fluids and smells. The dull thwack of a cleaver harnessing the power of metamorphosis, transforming a then chicken to a now poultry. Chopping blocks line the horizontal makeshift surfaces that emerge before sunrise and dissipate post meridiem.

These chopping blocks are lined with flesh daily. A butcher would segment the meat by cuts and joints for the anthropocentric gaze of human consumption. Each cut, fitting perfectly for further dissection on a chopping block.

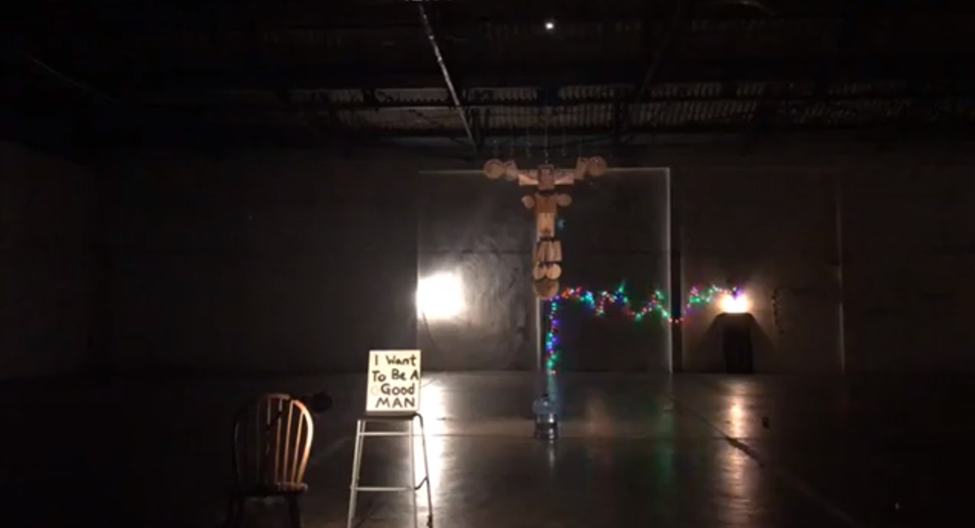

Chang Yoong Chia’s installation piece titled “Meat on the Chopping Block”《肉在砧板》paints the human anatomical form. It was only later when I realised it was the corporeal representation, onto circular and rectangular wooden blocks, crucifix in form and ready for sacrifice. The idea was originally conceived five years ago, a process of zoomorphism on the human body. Deconstructing flesh like a butcher, Chang segments the limbs as if readily prepared for further consumption, awaiting news for the next set of controls. Now, the fragility of the human body looms as a pandemic washes over the world. Wooden chopping blocks hanging, helpless, vulnerable. The body is open for inscription, for the viewers to navigate the geography of the corporeal self.

This year the installation has been reconstructed, curated and installed in KongsiKL by the collective MingChang, made up of Teoh Ming Wah and Chang. KongsiKL is an old warehouse arts space located in Jalan Klang Lama, Kuala Lumpur. Run by a non-profit organisation, the team focuses on producing interdisciplinary performances, exhibitions, competitions and workshops. For this exhibition, the venue also took up a productional role and proposed a 48-hour live stream exhibition opening when further movement control orders were put in place.

MingChang allowed for a free space “open mic” session alongside the installation, where friends of KongsiKL and the curatorial collective came to perform. My eyes follow the characters occupying the mise-en-scène, creating instant environments, responsive and reactive. Bodies, distorted, mapping the expansive gudang. Some of these moments include:

A dancer gliding across my screen, striking poses. Another character cycling into frame, a shadow of a bicycle following the rider, drifting in from stage right, to stage left. And back again. I barely look at the hanging chopping boards.

A human figure walking up towards the camera, determined. Right hand holding a detached limb, a hand to be exact. The right hand holding an indistinguishable object, too thin and too dark to determine the form. A wavering spotlight reveals the stationary figure as a masked person. The figure remains stationary for about 2 minutes, beckoning me to wait. I click away.

Ciabatta baked by the co-founders of KongsiKL enters the frame. A square table with a few loaves stacked on top of each other with a hand-drawn sign in chalk. “CIABATTA” was all I can make out from the pixelated live stream.

The responses ranged from haunting with moving, looming shadows on the back wall, to moments of looking through a peephole, peering into a film set ready for shooting, to a painterly still life scene. Watching the scene unfold, my focus immediately shifted to new additions creating a sense of playfulness, randomness and moments of intrigue.

Amongst the various lockdown strategies, KongsiKL took an alternative approach. Chang said: “This exhibition is possible because all parties involved are very flexible and there is not much bureaucracy and a lot of artistic exploration and curiosity”.

The exhibition enabled a horizontal world where bodies mattered. The absence of a physical audience compounded with the prickling “gaze of an unseen audience online” created an experimental realm that sits in between time and digital space. “The floor is free for self-expression”, said Chang, it is a space for all to perform and react. “Nothing was planned, it just happened.” In this realm, the performers were able to find a platform for release, away from the anxieties of the everyday. For a moment, the live stream collapsed the boundaries of the new normal imposed in the Klang Valley.

Clarissa Lim Kye Lee is under the CENDANA – ASWARA Arts Writing Mentorship Programme 2020-2021

The views and opinions expressed in this article are strictly the author’s own and do not reflect those of CENDANA. CENDANA reserves the right to be excluded from any liabilities, losses, damages, defaults, and/or intellectual property infringements caused by the views and opinions expressed by the author in this article at all times, during or after publication, whether on this website or any other platforms hosted by CENDANA or if said opinions/views are republished on third party platforms.