A traditional woodcarver, an anthropologist, a built environment specialist and a visual artist share the same desire for the diminishing art form of woodcarving to be preserved as well as to gain the level of recognition it truly deserves.

By KOAY CHOON SEAN for LENSA SENI

In a 2011 Christie’s live auction on the Asian 20th Century & Contemporary Art, a pair of two wood sculptures (Taichi Series – Sparring, 1991) by the Taiwanese artist Ju Ming closed its sale at a record-breaking HKD16.34mil (over US$2mil). It was the only non-painting-based artwork to gain its place in the top 10 for that evening.

Another bronze sculpture by the same artist was also sold at HKD6.62mil (just under US$1mil) during that auction. Both pieces are just two of the 62-piece artwork under the Taichi Series.

The context is far less rosy for traditional woodcarvers here in Malaysia.

As Burhan Ashari, a traditional woodcarver and owner of Seni Kayu Warisan from Terengganu puts it, “This art form could be gone in 20 to 30 years’ time if no proactive action is taken to conserve it.”

In Penang – where there are more traditional Chinese woodcarvers than anywhere else in Malaysia – the picture speaks of a grim future. The dwindling recognition for this art form is apparent by the slow disappearance of such works in personal and public spaces.

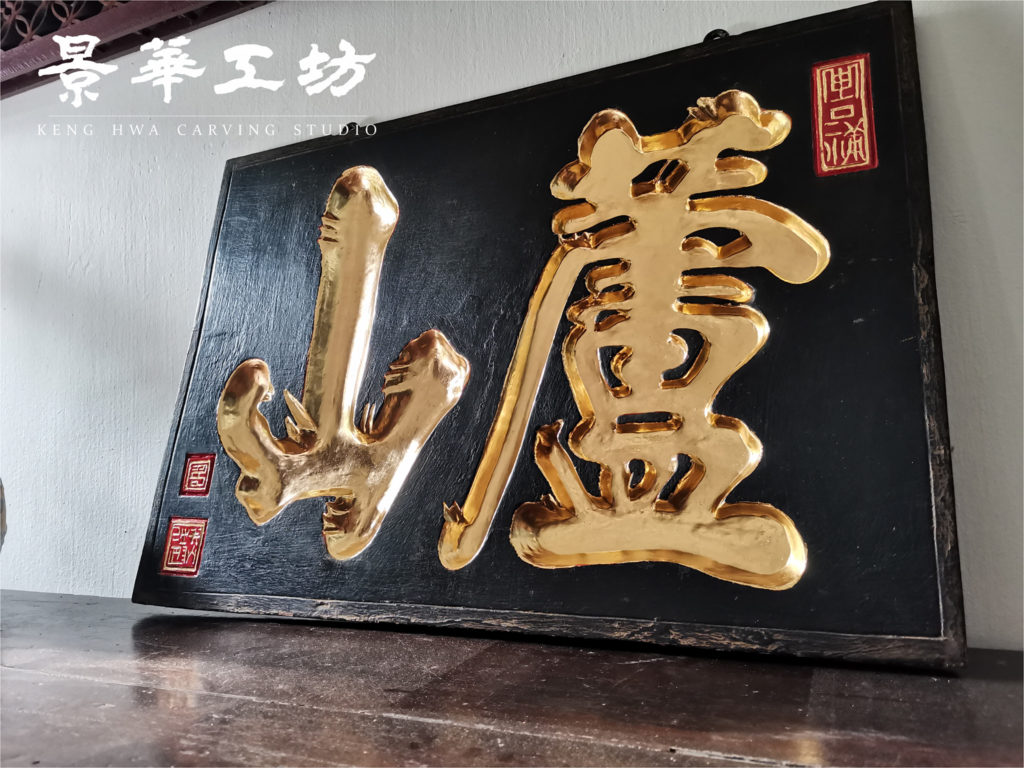

Tong Wing Cheong, the owner of Keng Hwa Carving Studio lightheartedly said, “These days, only religious institutions like temples continue to drive the majority of the demand for wood carving pieces – to the extent that they are now like a gallery for such works!

“Even then, sometimes they would rather bring in talents from other countries or even commission pieces from China or Taiwan. When this happens, there is no opportunity for local woodcarvers to showcase ourselves. There is no transfer of skill from them too, so it is definitely putting us at the brink of extinction.”

Tong added with a tone of melancholy that there are lesser apprentices under existing local wood carvers at present due to the lack of recognition for this art form, coupled with the challenging training regime.

Most of the current woodcarvers are nearing or beyond the retirement age, and their children wouldn’t consider taking over this practice as a career. Tong himself is probably the youngest woodcarver in Penang at the age of 35.

The emergence of mass-produced wood pieces is also endangering this art form by jeopardising the livability of existing traditional woodcarvers. They are undeniably cheaper, but they are also devoid of the human touch and the aesthetic beauty of imperfection, coupled with the cultural understanding needed in carving a piece with narrative of both the motives and the woodcarvers themselves.

This unfortunate phenomenon is an alarming sign of cultural dilution and a potential loss of an important building block of heritage. Traditional wood carving pieces have always been part of the cultural preservation forms that continue to tell stories from the yesteryears.

Muhammad Hijas, the Manager of Built Environment and Monitoring Department from George Town World Heritage Incorporated (GTWHI), agrees that woodcarving is very significant in the heritage context of Penang because it symbolises the design character of the space, the cultural beliefs as well as the influences of the building owner. It can also be said to be a vessel to carry the story and identity of the building across time.

That too, couldn’t be too far apart from the view of Lim Sok Swan who is an anthropologist trained in Taiwan. “Woodcarving pieces are an implicit form of cultural preservation because while they contain cultural elements, they can be present in a space without blatantly causing discomfort to others of different beliefs,” as she puts it.

Going further than that, she also thinks that the organic nature of wood embraces the concept of impermanence of life and evolution of the natural environment unlike any other materials. “The graceful aging of wood carving pieces will definitely serve as a good instrument of reminder to life’s fragility.”

Therefore, we can’t deny the significance in preserving this art form for the future. The three-dimensional form of woodcarving pieces contextualises the concept of originality as crafted through the hands of the artisan. You can’t reproduce an original woodcarving piece in its entirety and share it like any digital file – which means you can’t digitize this art form for NFT (Non-Fungible Token) either! You can buy the art via cryptocurrency but at the end of the day, ownership of a tangible, non-reproducible artwork is what matters towards giving it the premium value and appreciation.

However, the general understanding of preservation in this context is rather insufficient because it is not just about keeping things in the same state in order for it to remain alive. The foundation of traditional wood carving has mostly been about responding to functional and cultural needs, as Tong would agree.

For long-term preservation to happen, there is a need to elevate this art form beyond its reactive nature in Malaysia; that is, to also be a creative expression of original ideas or artistic views of the woodcarvers.

Ch’ng Kiah Kiean, a Penang-based visual artist and owner of KaKi Creation, is also of the view that there is a world out there to explore for the woodcarving artist other than being confined to the functional mindset of their crafts. He explained, “A revolutionary breakthrough is needed in order to create a new narrative for this art form, and to be recognised as part of the fine art movement here in Malaysia.”

Ch’ng coined a good example during our conversation: batik. From just the concept of a wearable, local artists like the renowned Datuk Tay Mo Leong elevated the art form to a whole new level of appreciation, both by the supporters and wider audience alike.

What follows after that is the value growth of the artwork, which in all honesty is important to encourage new blood into the circle who will then continue to build upon new narratives for this art form. Woodcarving is highly revolved around techniques and as such, is adaptable to manifest in various mediums as well as forms.

There is no need to compromise on the cultural foundation of the art form despite the above proposition on creating new paradigms. As mentioned earlier, Ju Ming, who was trained as a woodcarver, expanded his depth as an artist by refining and incorporating his woodcarving techniques into sculptures – as evidently portrayed via the 62-piece Taichi Series which represents one of the oldest Chinese arts in the world.

The path of incorporating technology into the form is also a viable branch of reinterpretation, as shown by the Japanese woodworker turned “automation artist” Kazuaki Harada using the form of woodcarving. Closer to home, Kuching-born sculptor Anniketyni Madian proves to us that weaving our heritage into contemporary artworks using wood carving techniques is beyond doubt, more than possible. Moreover, they can be worthy to take centerstage in ritzy spaces!

In concluding his thoughts, Ch’ng asked: “The foundation is already there, but how and what are we doing to encourage the breakthrough to happen for existing woodcarvers? Will a collective be a good nurturing ground for new ideas to be borne by encouraging dynamic interaction among wood carving artists, or discourse even?”

For more on Keng Hwa Carving Studio and Tong, visit the Facebook page, 景華工坊 Keng Hwa Carving Studio. Apart from traditional woodcarving, he is open to converse on the subject of Chinese culture and preservation of heritage. Keng Hwa Carving Studio also organizes workshops for the public from time to time.

KOAY CHOON SEAN is a participant in the CENDANA ARTS WRITING MASTERCLASS & MENTORSHIP PROGRAMME 2021.