What makes a poet? We speak to two people behind the pen: Kulleh Grasi and Charissa Ong TY wax lyrical about their craft and aspirations.

By NABILA AZLAN

How do you paint a picture with words and phrases? We ask two poets – both of whom are paving their way internationally – on what keeps their passion for poetry alive, their writing processes and some frequently asked questions in relation to being a poet today in Malaysia.

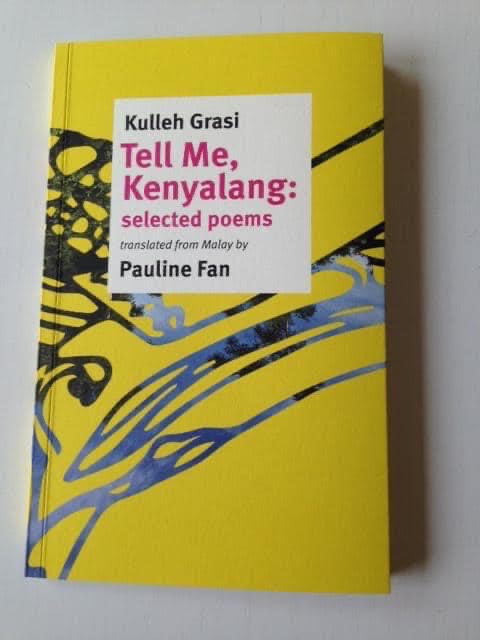

Kulleh Grasi is the nom de plume of Royston John Kulleh Sylvester Angkabang, 38, from Sarawak. Born in Sibu and raised in Sri Aman, this Iban poet is also a social activist and lead for musical group Nading Rhapsody. He writes patriotic, moving verses regarding homeland, identity, nature and mythical folklore. His book, Tell Me Kenyalang (written in Iban and Malay) translated into English by Pauline Fan, was his first, published by New York-based Circumference Books.

You might know Subang Jaya-based Charissa Ong Tse Ying, 30, aka Charissa Ong T. Y., from her poetry collections Midnight Monologues and Daylight Dialogues. She currently heads the Digital Product Design team at Inmagine and her publishing company Penwings Publishing. Since the latter’s inception, Ong has sold 29,000 poetry books. She instills nostalgia, romance, notions on heartbreak and familial ties in her poems and on occasion, writes magical fiction short stories.

How do you find yourself crafting poems?

Kulleh: I am not sure myself. I have always been nostalgic and critical. I used to stutter when I was younger, so I guess that I became inclined towards written communication rather than verbal. My penned experiments began as early as 9 or 10, with me scribbling away my emotions on scraps of paper and small notebooks. Honestly, I started with a limited vocabulary. Growing up in a small town, my childhood playground included a mobile library and a football field. Only after I had grown out of my shell, did I get to “explore” encyclopedias and readings on metropolitans beyond my reach – and my poetic journey took flight. I was simply a kid who wanted to anchor my dreams through words!

Ong: In 2016, I broke up with my university boyfriend. In my free time then, I poured my misery into reading and writing short stories on my blog. Poetry came later when I felt like short stories were beginning to take too much of my time. I was first writing for myself – I wanted to have something that I was proud of. I needed a place to escape and I found that in writing. Now, I do it for my readers too. The responses and reactions to my writing are very warm and loving.

Would you say you are different in real life, as compared with how you are in your written work?

Kulleh: Not by much, as I put only my sincerest thoughts down. I believe outside of my writer self, I’m just a regular Joe.

Ong: People have told me how I’m bubblier in person than in my poems – but my writing is literally me when I’m having my inner monologues.

How many languages are you fluent in?

Kulleh: I am able to converse in Malay, English and Mandarin – I went to a Chinese-speaking school. My mother tongue is Iban, although I am also fluent in other ethnic-focused languages such as Bidayuh Biatah, Kelabit and Penan.

Ong: I can read, write and speak Malay and English fluently, with some basic Mandarin and Cantonese. I speak English most of the time and it is my main writing language but I have tried writing in Bahasa Malaysia before.

Describe your writing style, and how you arrived at this style.

Kulleh: I write according to my heart’s desires – honestly, writing style hasn’t been a focus of mine, as most of the time I was thinking they were not meant for publishing. Having broken that wall, I have found myself at a crossroads between my raw writing style and what my readers were anticipating. Convinced by the reactions I’ve received, I shall continue writing like I always do. I believe my writing will continue to evolve.

Ong: I find beauty in rhymes, so I use them a lot. They feel nostalgic as I am heavily influenced by Disney music, which I have listened to since I was a kid. I have experimented with other styles throughout my career, but somehow rhyming has become my most consistent cadence.

When it comes to your process of writing, how do you keep track of your feelings for later? Is there a preferred way for doing this?

Kulleh: Usually, the notes I keep to develop certain works may not be so important in the end. The feelings remain. I’m pretty old school, I write on small notebooks when I wake up after having dreams. I also use voice notes at time.

Ong: I keep key words and notes in either the “Keep” or “Notion” app and get back to them whenever I have the time. I try to keep the momentum of writing a poem a week and reading every night to make sure my quality persists. I start with a very terrible draft and leave it to my perfectionist side to then fix it until it becomes a piece I’m proud of. I do most of my writing on my sofa and bed.s

Who are your books for?

Kulleh: For anyone who finds them.

Ong: Book haters and “bookstagrammers” – I want people to fall in love with reading just like I did. I wasn’t a reader until I picked up the Twilight saga at 17. Reading was easy, I fell in love with the hobby immediately.

Who are some of your go-to writers or books? Favourite genres?

Kulleh: Poets turned writers; Hok Sok Gie (Mandalawangi-Pangrango) and Latiff Mohidin (Tenang Telah Membawa Resah). My favourite translated book is Rainer Maria Rilke’s Letters to a Young Poet.

Ong: Anything fantasy, really – Patrick Rothfuss, Sarah J. Maas – as well as sci-fi or dystopian fiction. Non-fiction books focused on war and the holocaust. My interests are wide and not particularly skewed in any one direction.

What are some of the challenges of being a poet in Malaysia in this day and age?

Kulleh: Poets are in abundance, but for sustenance sake they need to delve into the spirit of writing. We have many writer-turned-poets here but not as many of the opposite. I feel that the exclusivity of the subject and the understanding of it poses a challenge here in Malaysia.

Ong: Your work has to be relevant on a global scale. Now that everything has gone digital, you’re competing with the world – everyone needs to know that you can write.

Can anyone be a poet?

Kulleh: Anyone can be a poet; you simply need to look into your own emotions. On a scholarly scale, a poet has to tread carefully in understanding linguistic contexts, meaning and symbols. The rest lies upon self-reflection.

Ong: Yeah, you just need to define your purpose in writing. If you are writing for yourself, fewer rules apply.

Do we need more poets going forward?

Kulleh: Poetic calling is personal and organic in its nature. We need more great writers with a holistic grasp of poetry.

Ong: Of course, we do. We need more people to challenge ideals, perspectives and tradition. The only constant is change – we need ideas.

Any words of wisdom to inspiring poets?

Kulleh: Be not scared to dream.

Ong: Start imperfectly. Do not wait for inspiration, as depending on your emotions is the most unreliable way to start something. Use emotions instead to fuel your work when you are already in flow. Discipline and being unafraid of imperfection are what will get you started.

Just in! Kulleh is heading for the 2022 Venice Biennale! He leads the indigenous music project, Kulleh Comrades, who will be performing at the gathering of international indigenous artists, curators and thinkers, known as aabaakwad (It clears after the storm) from April 21 to 26. Joining him on stage at the Sámi Pavillion are Iban musician Gabriel Fairuz Louis, Dayak Cultural Foundation musicians Stanny Benedict and Boy Nelson, singer Jen Rossum and music teacher Matt Dalin. See more on PUSAKA’s Instagram.