To get to know a person, I like to have a chat with them over coffee. The topics can range from talking about similar interests to things that impact their life. Having deep conversations using items or situations as examples to support our views allows me to learn both about them and myself.

By WAI LU YIN for Lensa Seni

Moka Mocha Ink streamed Teater Modular’s three-part online series, Teater Atas Meja (directed by Moka Mocha Ink’s co-founder Ridhwan Saidi) on Vimeo and its Instagram page. Inspired by UK theatre company Forced Entertainment’s Complete Works Table Top Shakespeare, performers convey the stories through their characters – as humans and through everyday items such as a frying pan, sausages and cups – on unconventional stages. Using these stages creates an approachability, enabling them to reach wider audiences and create conversations with them.

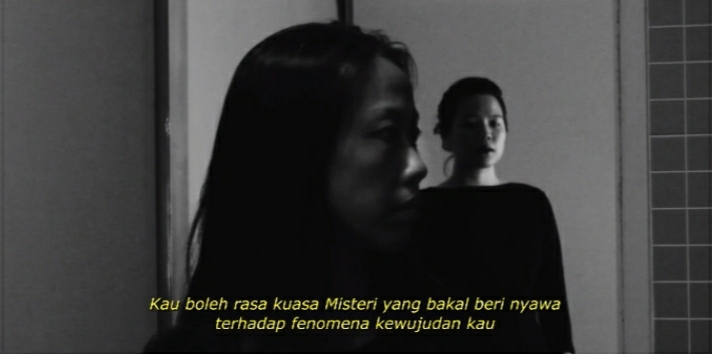

Berat Dosa Siapa Yang Tahu? (The Weight of Sin) explores the unfulfilled desire to be loved, physically and emotionally. Kurator Dapur (Kitchen Curator) follows a married couple tackling their roles in the art world and household. Erti Mati (The Meaning of Death) presents a philosophical dialogue about death between a human and the angel of death.

Ridhwan takes the initiative to explore new territories in literature by transforming plays into theatrical story-telling experiences. The three playlets (short plays) invite the audience to critically think about the complex topics of life and death in different dimensions. In Berat Dosa Siapa Yang Tahu?, the macho sausage man explains the levels of hell and heaven where people are placed after weighing their sins. Contrastingly, the angel of death, Ismail in Erti Mati tells Tsabur that when he dies, he will become “everything and nothing” in the cycle of existence. Watching these two parts, I hadto take a moment to ask myself – What would happen to me, or anyone, in the afterlife after we say certain words and do certain things in this life ,? Kurator Dapur’s dialogue showcases two contexts –the art world and at home – that makes us reflect on our own roles in life, career and relationships. For example, the wife sees the groceries as part of their upcoming exhibition but the husband wants to buy groceries to use together at home. This leads to a huge argument because the husband didn’t tell the wife of his intentions earlier. Their conversation raises the importance of communication so we can understand the differing contexts of what we say and do.

Believing in sustainability, Ridhwan Saidi encourages the actors to utilise any materials and spaces that are available to them. For this series, the staging and set design were very creatively done. Both Berat Dosa Siapakah Yang Tahu? and Kurator Dapur were filmed in a park, complying with social distancing measures, while Erti Mati was filmed at home. The adaptation and improvisation showcased a great balance of acting and puppetry.

What I like most about these playlets is how everyday items are interpreted and used as metaphors and analogies. Each item gives a deeper understanding of life and death. In Erti Mati, Ismail and Tsubar base their discussions around an empty and full cup, water coming from the sea, and board games that convey contradictions of existence and individualities. The frying pan in Berat Dosa Siapakah Yang Tahu? is used as a scale to weigh sins and as a torture mechanism to fry macho sausage man and skinny crabstick boy to satisfy cravings. In Kurator Dapur, the durian is used as a powerful metaphor for a far-reaching range of categories – sex, religion and politics. After an argument, the wife also takes the durian as an analogy of how her husband sees her on the outside, and not the inside.

However, this mix of puppetry and acting created some distractions, and I found myself straining to grasp the dialogue at certain points. The actors are reading the script while doing puppetry and talking to each other, minimising eye contact and chemistry between actors. As a result, their emotions aren’t effectively conveyed . The background audio of classical music, while meant to complement the scenes, sometimes ended up drowning out the actors’ voices. The translated subtitles do help, but I wish I could hear original audio better.

Teater Atas Meja brings the heavy topic of “life and death” into conversations that prompt us to talk and think about it. Some might be curious to know how life is while others fear death. With items being used to explore “life and death” and the addition of social context, these conversations with different layers of meaning are easily understood. They make us realise that we need to appreciate what we have in our lives, live in the moment, and look forward to the afterlife once we are dead.

Ridhwan and his team challenge themselves in portraying poetry and plays in unconventional spaces. From a blackbox theatre space to a table, with everyday items lying around, they find innovative and sustainable ways to bring “text-based” stories to life on stage. Whatever space they are in, physical or online, they succeed in sparking engaging conversations through theatre.

Wai Lu Yin is a participant of the CENDANA – ASWARA Arts Writing Mentorship Programme 2020-2021.