A smart-looking exhibition exploring the position of Asia within modern global capitalism, Look East Gone West manages to cover all bases without crumbling under its own weight.

By ELLEN LEE for Lensa Seni

When you make an appointment to view Ho Rui An’s Look East Gone West at A+ Works of Art, Sentul, Kuala Lumpur, the voice on the other line recommends you to set aside at least two hours to get the most out of the exhibition. Why two hours, for an exhibition that only takes up two small-ish rooms?

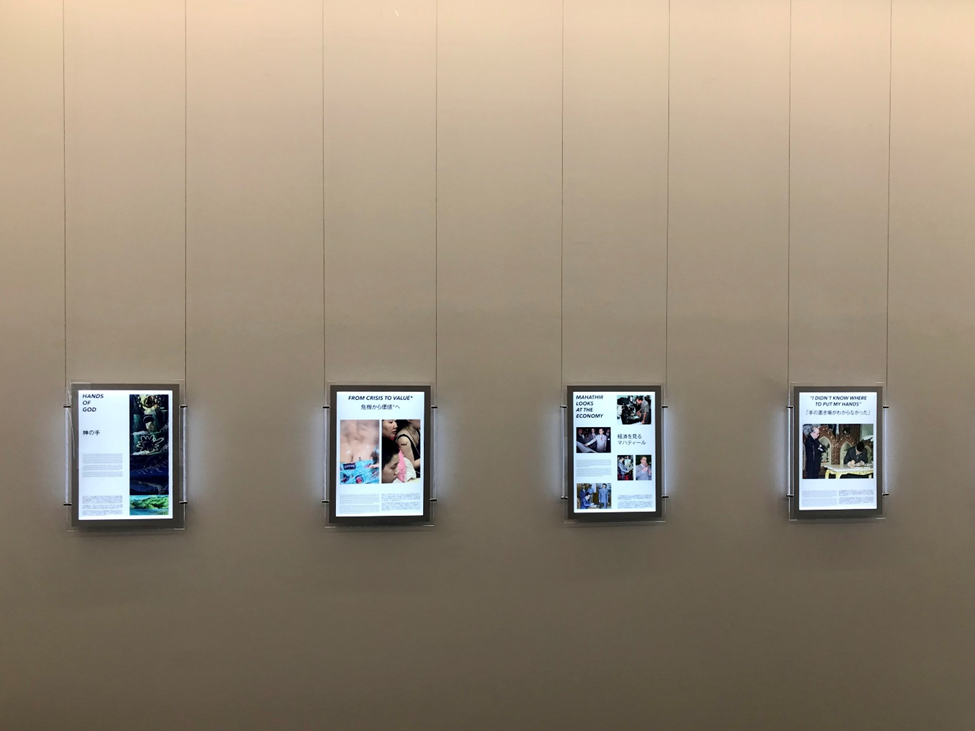

The great bulk of that is taken up by Asia the Unmiraculous (2018–ongoing), a lecture and video installation that includes the hour-long titular lecture, a tabletop setup of books and issues of TIME magazine referenced in the lecture, and a series of lightboxes that document an Inventory of the Unmiraculous in Asia, in both English and Japanese. Less epic but equally substantial is Student Bodies (2019) in the next room, a video work projected onto one of the gallery’s walls.

For a text-heavy installation, Asia the Unmiraculous is surprisingly crisp and accessible. The items in the Inventory act as beautifully-crafted textual supplements to the lecture without straying too far from the visual aspect of visual arts. The topical issue here is the dizzying rise, fall, and eventual slow rise again of Asia as an economic superpower, with a focus on the financial crisis of 1997. (It should be noted that despite the exhibition’s title, the regions of Asia specifically being explored are East and Southeast Asia.) A story of hubris both ways: on the part of the West, an empire sliding into decadence, grasping at its last few straws, but also on the part of the Asiatic East, who “miraculously” overcame stereotypes of its backwardness only to accept bailouts from the rapacious International Monetary Fund (IMF) after the fall.

Ho and the show’s curator, Kathleen Ditzig, are both from Singapore, and both are participants of contemporary art-world internationalism, with Ho’s name being a regular presence at various major international galleries and biennales. As an artist from the East who’s largely operated in the commercial crossroads of the world, he is perfectly situated to view Asia from the perspectives of both an insider and an outsider.

The show’s modus operandi is a slow dissection of images to reveal their larger intentions and implications. Disposing of a strictly academic and event-driven narrative, he instead uses an Adam Curtis-esque style of juxtaposing political commentary with pop culture references in order to extrapolate the macro from the micro. The installation begins with images of clear historical and propagandistic significance, images that would be obvious inclusions in any syllabus on the politics of representation, but the quality of images being picked up towards the end are more like visual detritus, or “memes” in contemporary Internet lingo. This perhaps reflects the more fragmentary and diluted power of images with the rise of Internet technology, but it also saves the installation from heavy-handedness by introducing a touch of humour and irony.

The first items in the Inventory are racist American depictions of (East) Asian labourers as servile and miserly, accompanied with a reference to a remark by Karl Marx that the Asian labourer would never achieve class consciousness due to their historic servility. This is closely followed by TIME magazine covers that feature various Asian nations for the first time, which the artist wryly points to as the moment when the region finally “graduated” from National Geographic. Beginning as ethnocentric specimens, the populations of the region have now become viable capitalist powers capable of speaking for themselves and saying things worth paying attention to. Also on the Inventory are the loaded portrayals of Asian abjection and prosperity in American movies, reflecting less the reality on the ground but more of a Western insistence on holding onto the National Geographic-era of tropical slum exotique images.

The critique being explored here is not about capitalism within East Asia, or about the class relations between the Asian labourer and his employer, but rather about Asia’s position within global capitalism. The “unmiraculous” is not the severe destitution that can be found within Asia as a direct result of its attempts at playing industrial catch-up, but rather Asia’s initial, unassuming, post-colonial status as a region that appeared to pose no threats to the West, up until the moment when it did. The “miracle” (to the West) was how the Asian nations managed to disprove all the myths about itself, from Marx and conservative commentators alike. The Asian labourer with his tentacular and competitive limbs continues to toil behind the scenes, discreetly, in languages unknown, while the West shakily attempts to reassure itself of its continued relevance.

Student Bodies (2019) clocks in at a more viewer-friendly runtime of 20 minutes and reveals more of Ho’s camera and film skills. It recounts the changing status of the student in Asian modernity, using the “student body” as a symbolic body politic. It opens with the story of the students of Satsuma and Chōshu in 19th-century Japan, the first Japanese students to study in the West who did so in secret transgression against the country’s isolationist policy at the time. From this first instance of education as something worth making sacrifices and exceptions for, a clandestine activity to usher in maturity and modernity, the film then goes on to recount various leftist student movements around the region that met extremely violent ends. The unsaid implication here is that radicalism among young students is simply the product of Western indoctrination, a display of ingratitude against tradition and ancestry. (A mode of reasoning which many Malaysians may be familiar with.)

Finally, the film ends with the Asian financial crisis and the subsequent loans from the IMF, the opening of national markets to foreign capital resulting in the destabilisation of state authority, and the subduing of the student body politic with mass popular culture. The figure of the student morphs into the figure of a customer-client for the increasingly commercial and internationally-minded university, a gross hijacking of higher education that’s emphasised by the slimy reptilian voices, meant to represent scholar-bureaucrats, who narrate the film.

In Student Bodies as in Asia the Unmiraculous, the plot twist happens when the IMF enters the scene. This is the point that Asia hangs its tail between its legs, gives up the national characteristics of the modernising mission and embraces the global market like the rest of the world. For better or for worse, a globalised world destabilises national boundaries and identities, and the postmodernist abandonment of stable principles produces a subdued student body population that is mostly progressive but not radical, to be managed rather than intellectually engaged with on any meaningful level. While the figure of the East Asian labourer depicted by Americans at the start of Asia the Unmiraculous may have been racist and false, at least it was a stable archetypal enemy. Now, identities are disintegrated; there is not one who has more power over the other, and at the same time there is no such thing as being truly “Asian” when Western multinationals start to root themselves all over the region. A recurrent motif, in both films, are wide shots of an empty sea, waves gently rocking: fluid identities, fluid markets, fluid principles.

The preferred mode of transmission in this slippery, liquid world is images, which cross language barriers. But does anything really change once an Asian country makes the cover of TIME magazine? Can images be exchanged for politics? Do images influence attitudes, or vice versa? In Ho’s analysis, the West have long been the ones with the monopoly on image-production and -distribution. But now, in a digital world that democratises access to images, can the East also challenge the West on the cultural battlefront for the hearts and minds of the world?

Towards the end of Asia the Unmiraculous, the power of images shifts hands: now it is Asia’s turn to represent the West. Asia’s imaging power, Ho seems to suggest, appears in their naive and overly-literal mistranslations of Western images, such as a meaningless tattoo of the word “value” on a Chinese woman’s arm, or street vendor stalls in Thailand with names like “Pork Knuckles IMF”, misinterpreting “IMF” as synonymous with cheap. Asia, it seems, is the distorting hall of mirrors for Western prosperity, disarming it, making it ridiculous. As for Student Bodies, the film ends with a montage involving a cutesy throwback boy band and a clip from a horror movie: two cultural modes that Asia has proven to particularly excel in, to the point where they’ve penetrated the Western cultural mainstream despite language barriers. For an exhibition that opens up with racist stereotypes of Asians by Americans, it doesn’t do much to dispel the myth that Asians are anything beyond grotesque, superficial, annoying, ridiculous, and unmiraculous. (Aside from itself being an extremely polished and sleek work of art.) But perhaps it is not and has never been about race, but rather about the (non-)system of global capitalism, which makes fools of everyone trying to beat it.

Ellen Lee is under the CENDANA—ASWARA Arts Writing Mentorship Programme 2020-2021.