Now, nearly two years deep into the pandemic, the same conversations are still being held. But has anything changed?

By ELLEN LEE

When the pandemic hit last year, there was a frenzy of online conversations being organised among arts circles. Everyone gathered to wonder what it all meant for the fate of their professions. Many things were revealed; all the contingencies of the individual arts were thrown into sharp relief as practitioners asked themselves what they could provide to a nation in crisis. Now, nearly two years deep into the pandemic, the same conversations are still being held. But has anything changed?

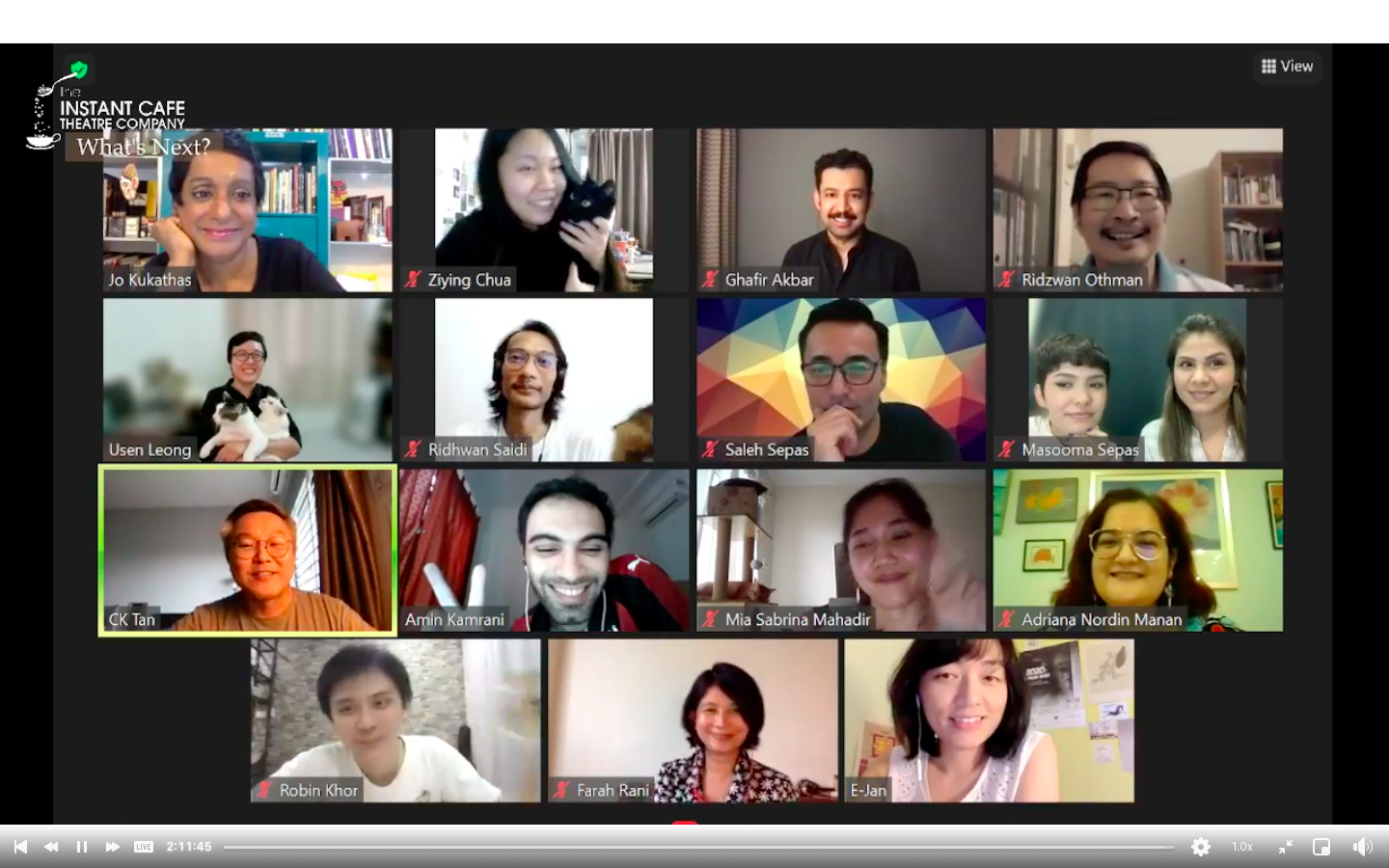

An online panel organised by Instant Cafe Theatre and moderated by multihyphenate-cofounder Jo Kukathas last Sunday seemed to jump slightly ahead of itself. Its title asked, “What’s Next?” when we haven’t even found an answer yet to “what now?” Overall, the two-hour-long conversation was more a casual check-in than an in-depth discussion.

The conversation gathered five performing arts practitioners and one educator. Also in the Zoom room were three translators and three interpreters. Between Jo and her six panellists, they spoke a combination of English, Malay, Mandarin, and Farsi. For a simple Zoom conference, it certainly had a high production level.

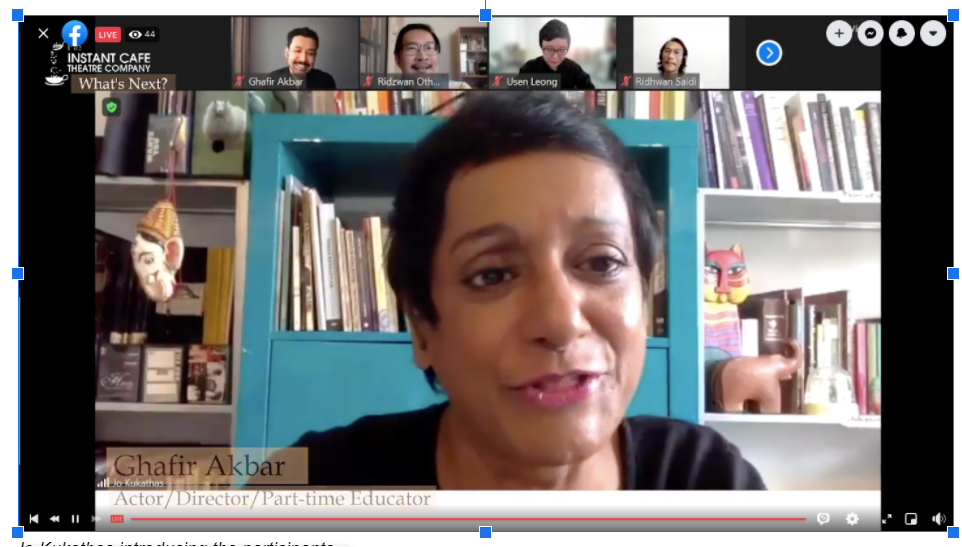

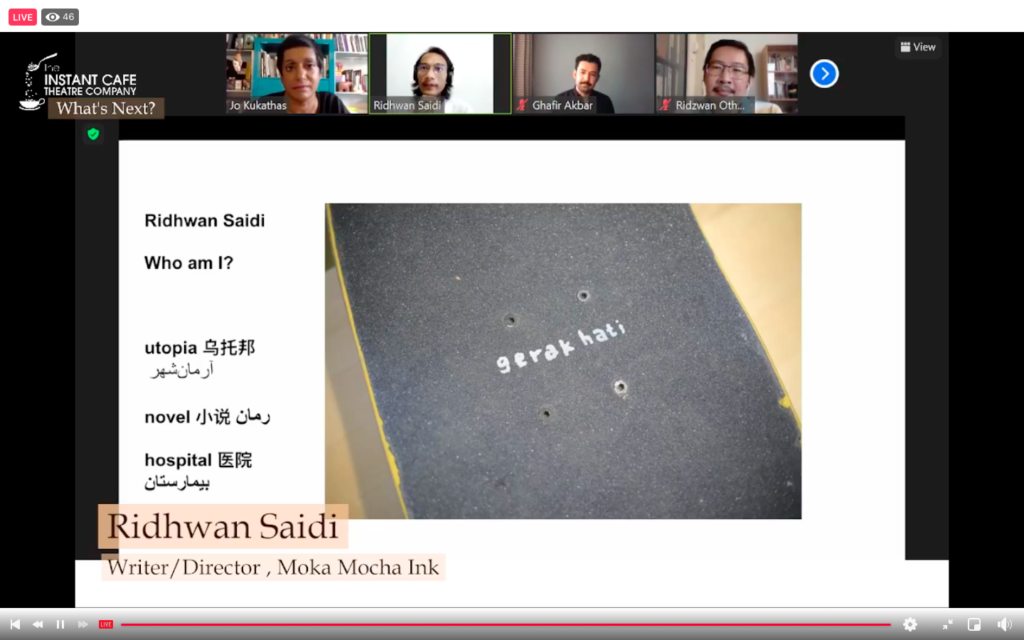

The panellists were Ghafir Akbar, an actor, director, and educator; Saleh and Masooma Sepas, a pair of directors, actors, and playwrights behind Parastoo Theatre who also happen to be Afghan refugees living in Malaysia; Usen Leong, a lecturer at a local college; Ridhwan Saidi, a writer and director who also runs Moka Mocha Ink, an independent publishing house; and Ridzwan Othman, a freelance writer, editor and proofreader.

Lockdown learnings

The discussion was divided into three parts, each consisting of a few simple question prompts. The organisation team did their best to encourage the flow of conversation, but, for the most part, it stayed on a superficial level with most participants simply responding to the prompts. Over a year later, Zoom still fails to replace the openness of in-person conversations.

Mostly, participants talked about general topics such as their pandemic discoveries, what they’ve been up to, and what projects they have in store for their future.

Ridhwan Saidi talked extensively about his new skateboarding hobby, a love that he’d rekindled during the pandemic after a major operation stopped him from pursuing it when he was a teen. Meanwhile, Usen, as an educator, shared about her students’ efforts to utilise digital mediums during the pandemic.

Usen also brought up last year’s Digital Parliament, in which a group of youths reconstructed a mock Parliament session over Zoom to show how easy it would be to reconvene Parliament digitally. “The Digital Parliament provoked my thoughts on how youngsters might not have the conventional experience of human-to-human contact, but they are equipped with another skillset that’s needed in this era. The mode of learning is changing, and if we do not change too, then we might not be ready for the new era.”

As for Saleh and Masooma, their points of conversation kept returning, understandably, to their home country of Afghanistan, where the Taliban continues to terrorise civilians while their President watches dumbly. These were sobering reminders of the worst horrors that exist in the world, horrors against which Covid-19 is just a minor irritation.

The Future

The pandemic has shaped and impacted everyone in different ways. Some, like Usen’s students, were experimenting with new, digital mediums in their practice. For Ridhwan, he had to re-think filmmaking for a socially-distanced world while shooting his 2020 film, No Love for the Young. He devised the story to be told in abstract fragments, which allowed him to shoot his actors separately, in small groups.

For others, the pandemic has not only inspired new modes of working, but also new modes of thinking. The enforced isolations have inspired Ghafir’s next endeavour, a meditation on loneliness entitled, How to Be Alone. That same enforced isolation meanwhile inspired Saleh and Masooma to create a play about domestic violence.

In Ridzwan Othman’s musing on what he wants for the future, he said, modestly: “My biggest dream is simplicity.” Earlier, he had spoken about his compulsive use of Excel as an organisation tool, and here he quipped, “I don’t get why, despite all my Excel sheets, I’m still short on time!”

Roadblocks

In one of Jo’s final questions, she utilised our new pandemic lingo to ask, “What are the current roadblocks to your creativity?” Most of the participants replied with personal shortcomings. Memorably, Usen, who had been speaking in Mandarin up to that point, made the group laugh when she said, “This one doesn’t need translation: I’m lazy.” Saleh brought the conversation out of the personal and into the political by speaking about his refugee status, or, “the roadblocks between humans.”

His comment was, like the pandemic, another chilling reminder of all the contingencies that creativity is dependent on. The pandemic may be the hot topic for the moment, but the truth is that there are already a myriad of existing “roadblocks” all over the world that prevent the free flow and expression of human creativity. “Roadblocks” such as poverty, war, or tyranny.

“When I’m on my skateboard, I feel temporarily free,” said Ridhwan in the closing remarks. “The whole point of art, of doing art, is to feel free. Even if it’s a temporary feeling, I feel happy.”

Even once the pandemic is over, there will remain many other barriers to freedom. The pandemic is simply a flashpoint, a phenomenon that forces the entire population to feel certain deprivations that have long been the norm for the less privileged among us. As such, the question of what purpose art can serve in a crisis has and will always be pertinent.

What’s Next? was an online panel organised by Instant Cafe Theatre on May 27, 2021. You can catch a recording of the discussion on Facebook.