By LILY JAMALUDIN

Kenangan itu, hanya mainan bagimu, running at Mutual Aid Projects from Dec 19 to Jan 23, 2020, may be one of my favorite exhibitions of the year.

It’s tiny – consisting of a single diorama located in a small “showroom” inside the charming yet outdated Wisma Central on Jalan Ampang in Kuala Lumpur – but wrestles with Malaysia’s economic development in a way that is striking, original and incisive.

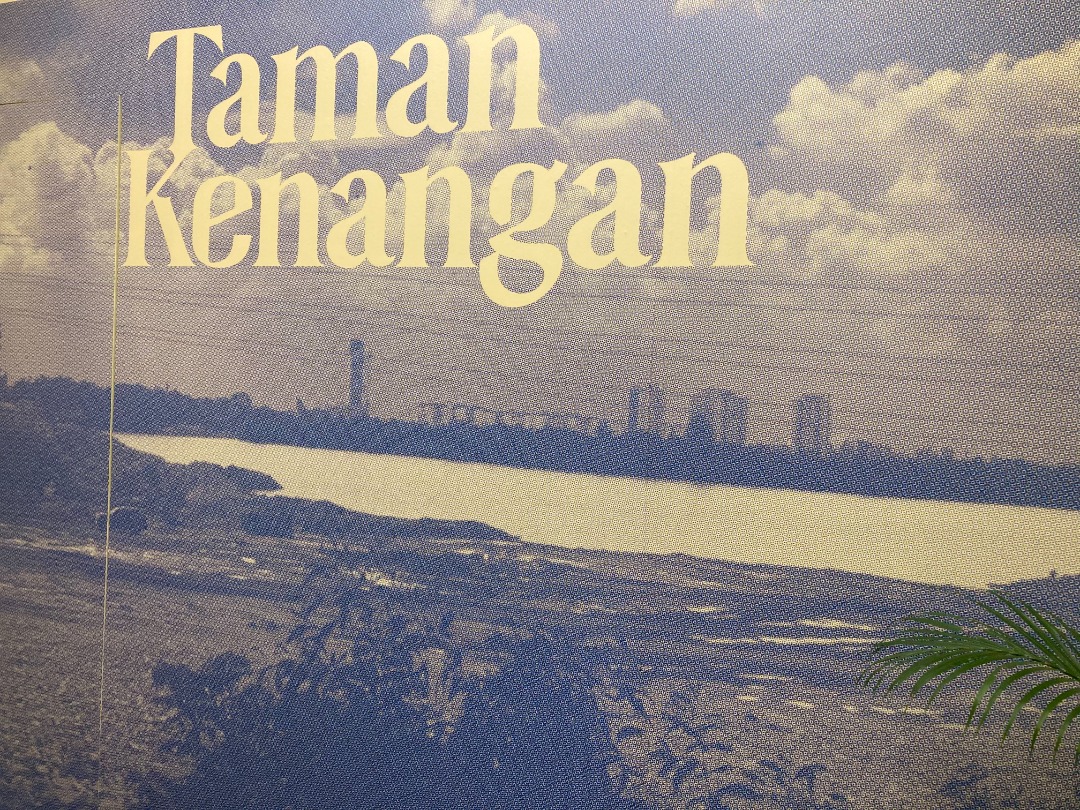

This site-specific installation is the second of a series by local artist Izat Arif, interrogating Malaysia’s obsession with progress and development. The first installation was held at Ilham Gallery’s Domestic Bliss, where Taman Kenangan was exhibited as a development proposal.

In this phase, the construction of Taman Kenangan has begun, and viewers are being sold the vision of a promising gated community.

Like other development projects in Malaysia, Taman Kenangan is brimming with potential, and the promise of the Malaysian dream.

Entering the showroom, a backdrop on the far wall proudly displays the name of the new development, while adverts that read like Orwellian doublespeak line the two walls.

“Taman Kenangan fosters the protection, restoration and exploration of Gunung Ledang,” one ad reads. On the other side of the wall, “Kehidupan di bandar dengan kesenangan yang tidak terbatas, perlu diisi dengan aktiviti yang lebih bermakna untuk membendung rasa kelapangan di jiwa.”

Meanwhile, a television advertisement in the showroom continues to play marketing messages on a loop. “Be part of the community. Register your desires,” the advertisements read. They promise an ideal living community: “Down to earth kampung style homes. Mountain view homes. Lake view homes.”

The showroom mimics the language of other real estate developments. But the advertisements feel hauntingly divorced from the reality of the project: that Taman Kenangan is being built upon a razed Gunung Ledang.

The diorama is the heart of this installation. What was previously a gargantuan and towering mountain has been cut like a square slice of cake, held up by tiny model scaffolding. Around the dismembered remains of the mountain, the land has been cleared, and vegetation exists only outside the gated community.

This is one of the key paradoxes presented in Kenangan itu, amongst many others: the development project’s claim of national progress and success, while visibly destroying the natural environment, displacing communities and reducing culture to a commodity.

Meanwhile, a tacky muzak rendition of M. Nasir’s Sejati – the song from which the installation derives its title – plays in the background. “Kenangan itu/Hanya mainan bagimu/Tinggal bertanya/Erti sejati/Yang telah engkau janjikan dulu,” read the lyrics on the screen.

Noticeably, the showroom doesn’t seem to locate itself in any specific moment in time. The design mashes together elements from the 1980s, 90s and 2000s, leaving viewers in a strange time loop. This is perfect, in a way, encapsulating the spirit of Malaysian progress: we are still in the same place, believing in a false dream promised to us years ago, forced to repeat a model that has not worked. It’s labeled as progress, but there’s no sense of moving forward.

Though it seems as if Izat and his collaborators have turned up the notch on the dystopic atmosphere of real estate development, the real strength of Kenangan itu is in its familiarity. It doesn’t look very different from a real showroom that would accompany any new development project. In fact, it feels recognizable. But in mimicking the world of real estate development, Izat manages to expose the concepts of development, progress and modernity in sharp clarity.

This dystopia isn’t imagined. It’s familiar. It’s close. It has already been arriving for years.

How different, really, is Taman Kenangan from other developments that have happened, and are happening in Malaysia? How far away are we, really, from arriving at the dystopia put forward by the installation?

Consider the recent move to degazette Kuala Langat North Forest Reserve. In its place, there are plans to build a business centre and a new development project, which would result in the displacement of over 1000 people (including Orang Asli communities who had already been displaced due to the development of KLIA), and the release of 5.5 million tonnes of carbon dioxide, amongst other effects.

And that is just one example. The exhibit brochure highlights numerous development projects taking place across peninsula that replicate the issues highlighted by Kenangan itu: Penang South Reclamation, Melaka Gateway in Malacca and Forest City in Johor Bahru.

So it’s timely, then, that Kenangan itu is being held now: at a time when many Malaysians feel jaded and cynical from failed and repeated promises, left behind in a loop of ambiguous futures, and at the mercy of the architects of our future: capitalism, progress, development.

What hope is there for the future? For that, we may have to wait for Izat’s next installation of Taman Kenangan, and the new sets of questions it will pose.

“I don’t believe art can change the world,” Izat explains to a group of viewers. “But it can ask a question. It can start a conversation.”

And maybe that is enough to wake us up from the delusion of progress.

Lily Jamaludin is a writer with the CENDANA-ASWARA Arts Writing Mentorship Programme 2020-2021.