Ivan Lam's 'Catharsis' confronts a literal sense of existence – that of mortality.

By MAE CHAN

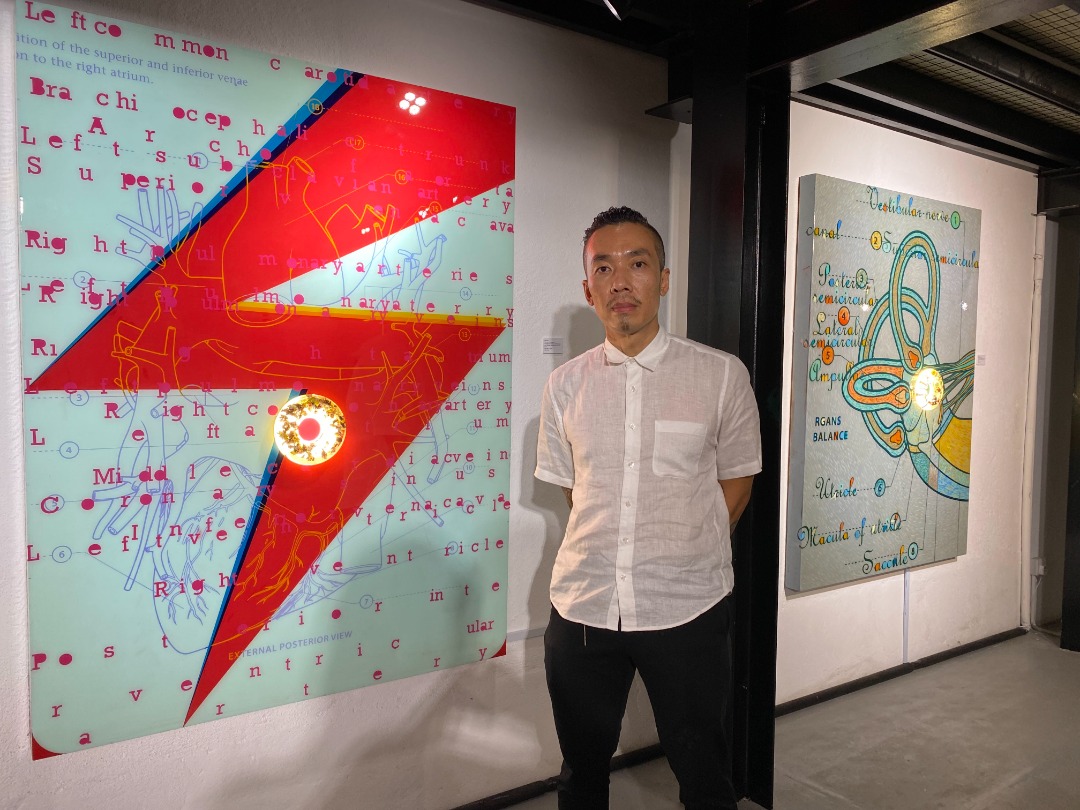

An Ivan Lam show always seems to surprise. But then again, anyone who has followed the visual artist’s work over any part of the last two decades would expect the unexpected.

In fact, for his latest solo exhibition, Catharsis at Wei-Ling Gallery, Oscar Wilde’s immortalised quote, “To expect the unexpected shows a thoroughly modern intellect”, resonates in more ways than one.

Lam is very much an artist for the modern intellect, being one of Malaysia’s foremost contemporary artists known for his strong multidisciplinary approach. From printmaking and painting to performance art and multimedia installations, among others, his virtuosity is matched by a keenness to go down the proverbial rabbit hole on a topic with introspective rigour.

The mid-career artist frames these visual conversations or contemplations from his own perspective as an artist, father, son, husband, Malaysian, or man. Indeed, if there is a common denominator or thread that fundamentally runs through any Ivan Lam artwork or show, it may well be that of identity.

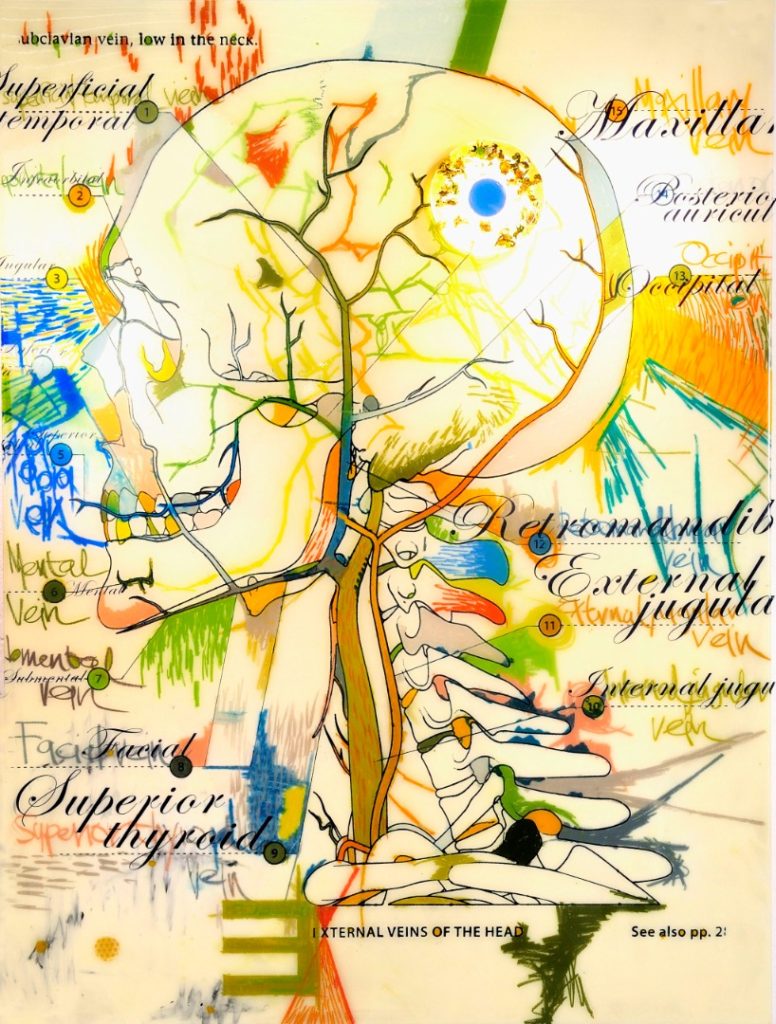

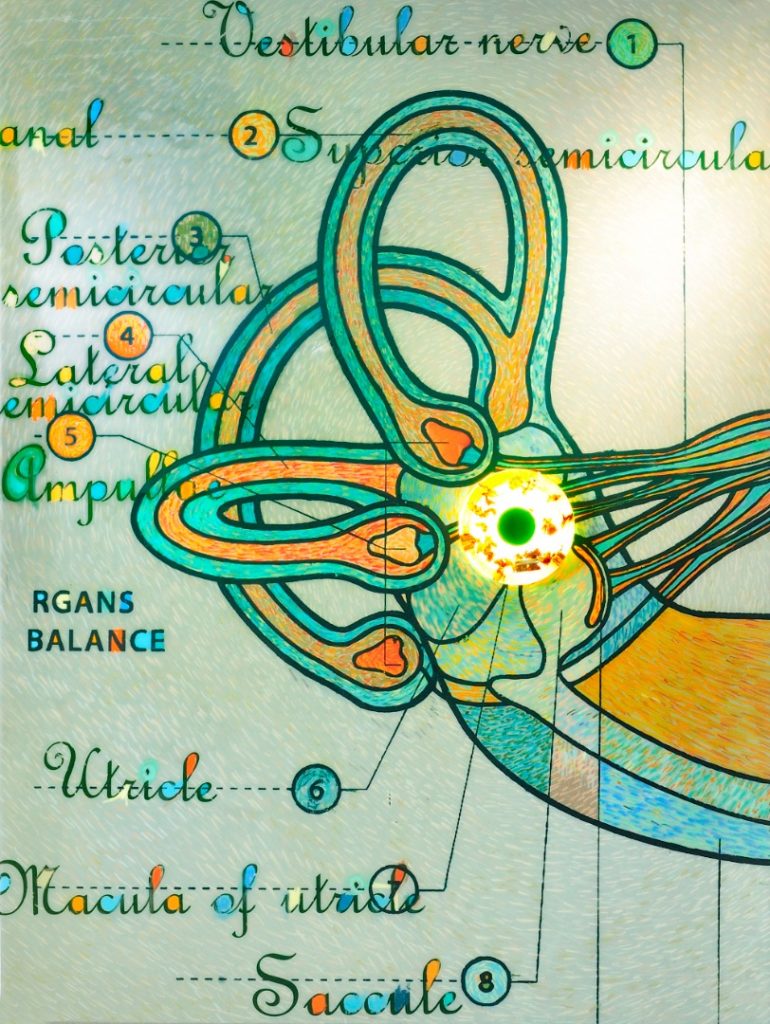

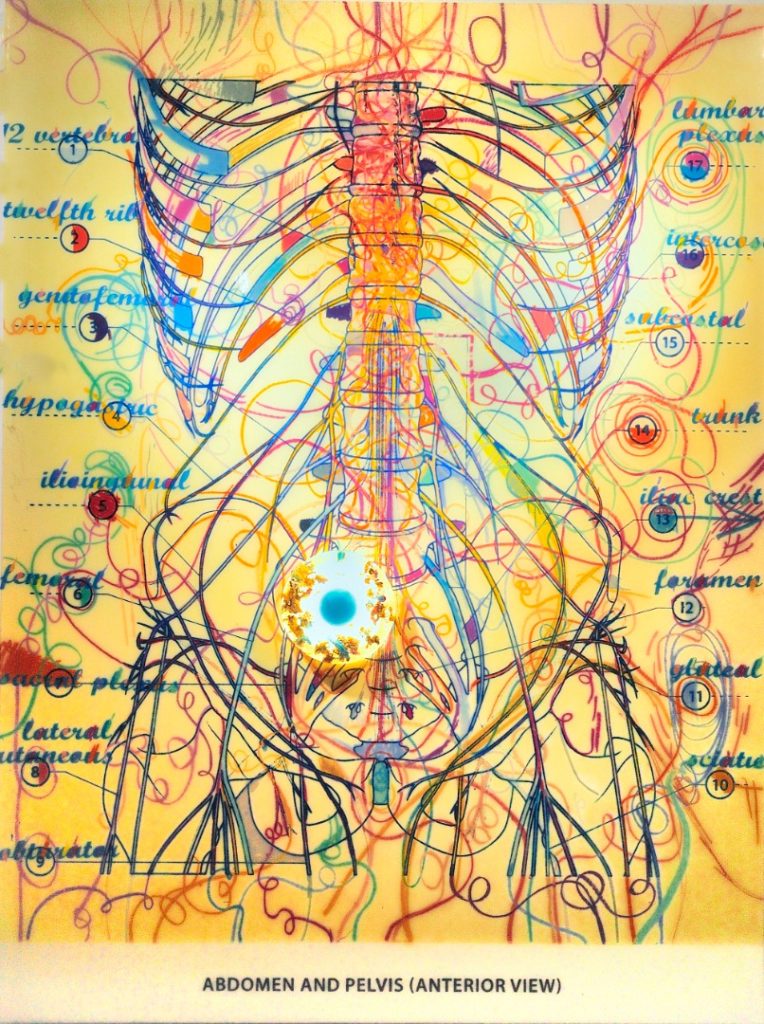

Catharsis confronts a more literal sense of existence, that of mortality. Five panels reveal images right out of a biology textbook, albeit with artful interpretation. Each represents an illness or medical condition Lam has had to deal with at various junctures of his life.

Migraine, heart palpitation, melanin and skin issues, vertigo, and most severely of all, polyps in the colon that were discovered just in the nick of time.

“About four years ago, I went for an annual checkup. The doctor rushed out and asked me, ‘How are you still standing?’ Turns out I only had two-litres of blood in my body at the time,” and a normal human being would have four to five litres, shares Lam. “I was immediately checked into the hospital, and had to receive a blood transfusion before it was safe to go under the knife, and they found four raging polyps.”

Then imagine waking up one day and slamming your head against the wall due to vertigo. “For eight months, everyday I woke up not knowing whether I would be disoriented. Then trying to sit up again without hitting my head the next day, and again and again.”

None make for a pretty picture. You will need to take in the detailed, somewhat clinical depictions inspired by medical textbooks. A skull, the ear canal, anatomy of the epidermis, and the entire abdomen and pelvic nerve system, then the heart – the most abstract of them all – marked by a striking red lightning bolt (there’s a hint at the side as to why). On each work are didactic markings, vinyl texts and numbers that seem like “fill-in-the-blank” workbooks.

But what arrests attention are the donut-shaped ring lights on each panel. In it are specks of scraped paint from his past works. It is a deliberate touch of visual continuity, but also a personal pun. “I wanted to play on “paint and pain”. Like a ‘pain(t) point’,” Lam laughs.

It reminded this writer of how I had walked into a semi-dark gallery earlier. “I switched off the lights because I would like for you to activate the artworks on your own,” he gestures, offering a rare opportunity to touch an exhibited artwork.

At the flick of a switch at a time, five panels became illuminated by donut-shaped rings of light, one per panel. Above the switches were statements that also doubled up as the artworks’ titles – Press here to time travel; Press here to teleport; Press here to appear; Press here to disappear; and Press here to reappear.

Lam reflects, “I used to struggle to accept having so many health problems. Like it doesn’t seem fair when I put in the hard work to take care of myself. Then there is the struggle of how I can make it better. So I think the process I went through here is in accepting there are things I can do nothing about.”

As they say, everyone processes pain differently. For the artist, deep diving into his medical conditions started out as a way of processing his physical struggles. “I bought medical books and studied my conditions, human biology. It didn’t make any of it go away, but mentally I can see more clearly, as if every one of it metastasised outside of my body.”

But the process also provided an escape from the mental and emotional toll it has taken on him, and his worry of what else is to come. In depersonalising his struggles, Lam’s catharsis is in the realisation that he is no different from everyone else – both biologically and as a human being trying to survive in this world.

Amidst a seemingly never-ending pandemic, this particularly resonates. “We wrestle and try to construct this narrative in our world, that maybe we can have control. We think if we work at it, we can direct how things go. But the truth is, we can’t, we can’t even control if we will wake up tomorrow, and it doesn’t matter who we think we are,” he emphasises.

As the last two years may have taught all of us, and as Lam’s many helpless situations have taught him, to expect the unexpected and to make peace with surrendering control are perhaps the skills we need most in an increasingly volatile world.

Fret not. As any good art does, Catharsis offers a reprieve from reality. Switch on and switch off, to banish the pain and darkness, to shine a light. To time travel, to teleport, to appear or disappear and reappear. “If only,” Lam smiles. “But in my art, at least you can.”

Catharsis is on at Wei-Ling Gallery until April 16. Visitation is by appointment only. To visit the show, kindly call/message via WhatsApp at +60322601106, or e-mail siewboon@weiling-gallery.com.