Creature Trilogy explores the multiple interpretations of the ways in which we deal with unknowns today through the familiarity of the human body.

By WILLIAM CHEW for LENSA SENI

In many societies, the cultural construct of a creature is used to make sense of the other and the unknown, be it mythical, mental or communal. This obsession in redefining the other has persisted over time and remains a critical question for many. Creature Trilogy, staged in January this year, explored the multiple interpretations of the way we deal with unknowns today through the familiarity of human bodies. This triple bill featured the works of dancers and choreographers Raziman Sarbini, Pexstret Liu Yong Sean, and Suhaili Micheline, each having returned home after practising abroad for several years.

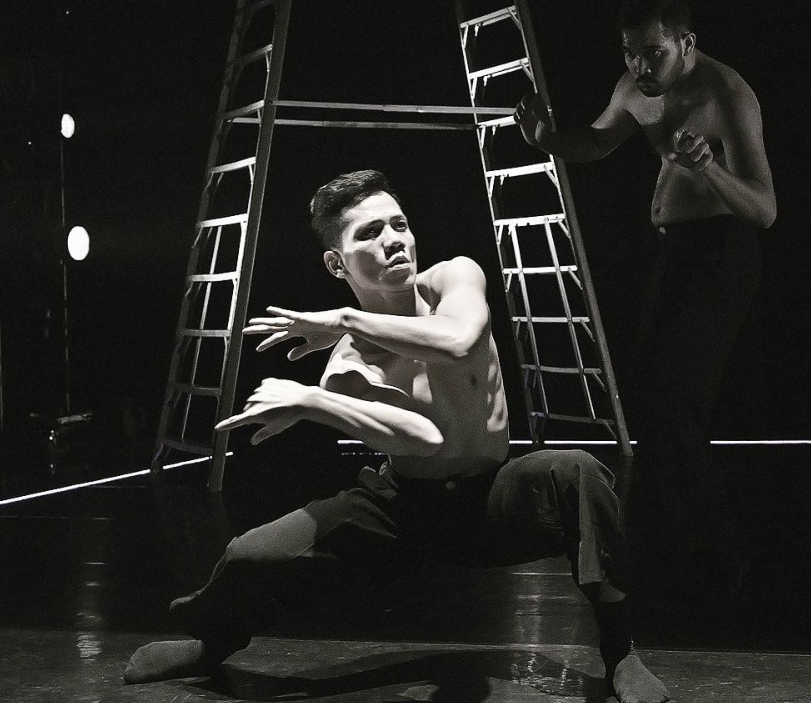

The show opened with Raziman’s The Other Creatures, performed by Naim Syahrazad and Raziman himself. The stage was set with a ladder in each corner and a strip of light on the floor highlighting the perimeter. Naim entered first from stage left, bare-chested with black pants, moving quickly towards the audience as if scouting for another presence. Raziman hid in the shadows for a while, staring intensely at Naim’s back while expressing a mix of charm and horror through his eyes, establishing a prey-predator relationship. Upon locking eyes, they spread themselves apart and circle around, anticipating and mimicking the other’s every move. The percussive clicking and crackling in the music added tension and emphasised the insect-like movements. The kinks and bends in their arms formed a Z-shape, much like a praying mantis.

The chemistry between them was intense when their bodies intertwined. Raziman came up close behind Naim, pushing one arm straight over the left shoulder as Naim tilted his head slightly to the right, before rapidly sliding the other arm under Naim’s right arm, wrapping around the waist, but just shy of touching. Both dancers, locked in this intimate arrangement, moved their torsos sideways, arms sliding past each other, confidently and explosively. Towards the end, using Max Richter’s November to build up to a heightened tension, the dancers pulled off even more dynamic actions, lifting and throwing one another across the stage. When Naim sat on Raziman’s shoulders, the stacked bodies gave an immediate sense of volume that could be measured with the ladders surrounding them.

Although the show notes state that Raziman drew ideas from the snakes and ladders board game to critique the power dynamics of competition and collaboration, I couldn’t help but notice the similarities with Nan Goldin’s The Ballad of Sexual Dependency, especially in the gaze that the dancers held for each other, and the signs of violence, control and passion between them. In this light, perhaps the idea of otherness here was not only in the physicality of their bodies, but extended into their ambiguous relationship and the other beings they turned into as they came together.

Pexstret Liu Yong Sean’s solo work titled Laced depicted the internal struggles of a one-sided relationship through a series of disparate acts. Dressed in a wedding gown that trailed gracefully behind him, Liu spread his arms out front and back, keeping his palms folded but fingers apart, curving his torso sideways and locking his legs in position. This resembled the gesture of a Chinese white pine, slightly off balance, but standing elegantly. Moving slowly but constantly, he arched his back to the audience and swayed his arms as if being blown by a strong wind. The agonising physical and emotional torment could be seen from his lower torso all the way up to his face.

Breaking out from his gown, Liu traversed explosively across the stage. Combining the sound of his body landing on the ground with accents of inhales and exhales, he explored an organic soundscape that resonated with his movements. Repeatedly knocking his head on a hanging mic, it swung back and forth with a rhythmic tapping echo, which he danced to. Humming a folk tune into the now swinging mic, he generated waves of crescendos. Grabbing the mic and flinging it around, we “heard” the speed of his arms. These random acts took apart and reassembled the relationship between sound and body. Seeking a narrative here seemed futile, and perhaps Liu’s intention was instead to make a spectacle out of this absurdity.

The second half was much more explicit, with slightly forceful acting and monologues of being cheated on. The final act resembled a fashion runway without a backstage. The endless doubting and changing of outfits revealed his insecurities and need to please his partner. The piece was bold with its experiments and naturally, some parts were more successful than others. However, the overall flashiness made for a refreshing take on the creatures we become under emotional turmoil.

To MusimMonstah choreographed by Suhaili Micheline and performed by Tay Hwan Haw, Amelia Feroz, Erica Lew and Teoh Zhi Lin showed us the visceral effects of mental disorder. The young dancers stood equally spaced, dressed in an odd mix of pyjamas, casual clothing and sportswear, moving like zombies to electronic music. Although the way they terminated their movements were not as controlled and synchronised compared to the more experienced dancers previously, the slight clunkiness in their moves worked well in the overall composition.

The dynamics between dancers were fluid. At times the ladies ganged up against Tay with menacing stares as he fell to the ground, and other times Amelia took on the caring role, chasing Tay around, seemingly wanting to calm him down. In the latter half, the group merged their bodies into a chimera-like assembly with Tay in the middle, Amelia and Lew held his sides, and Teoh knelt down in front grabbing his legs. Tay, overpowered by the other three, showed some resistance, but mostly moved under their control as they twisted and turned his body.

Throughout the chaotic acts within this piece, there seemed to be no sign of a narrative or character development, which might have been intentional to show the completely irrational and unsalvageable aspects of humanity. It was also unclear whether the set took place within Tay’s mind or in a mental asylum, leaving us with the question of what, or who, the creature was. The former allowed for a simple conclusion, but the latter would imply labelling patients as creatures. Crude as that may be, it seemed to reflect the perception that many Malaysians still hold towards the mentally ill.

The show as a whole not only captured the multifaceted ideas of creatures, be it sexual, emotional, or psychological, but also reminded us of the difficult task of re-examining what we perceive as repulsive within and without, in the hopes of becoming better creatures ourselves.

Creature Trilogy was performed at the Damansara Performing Arts Centre, Jan 21-23, 2022.

William Chew is a participant in the CENDANA ARTS WRITING MASTERCLASS & MENTORSHIP PROGRAMME 2021

The views and opinions expressed in this article are strictly the author’s own and do not reflect those of CENDANA. CENDANA reserves the right to be excluded from any liabilities, losses, damages, defaults, and/or intellectual property infringements caused by the views and opinions expressed by the author in this article at all times, during or after publication, whether on this website or any other platforms hosted by CENDANA or if said opinions/views are republished on third party platforms.