By HAMIDAH ABD RAHMAN

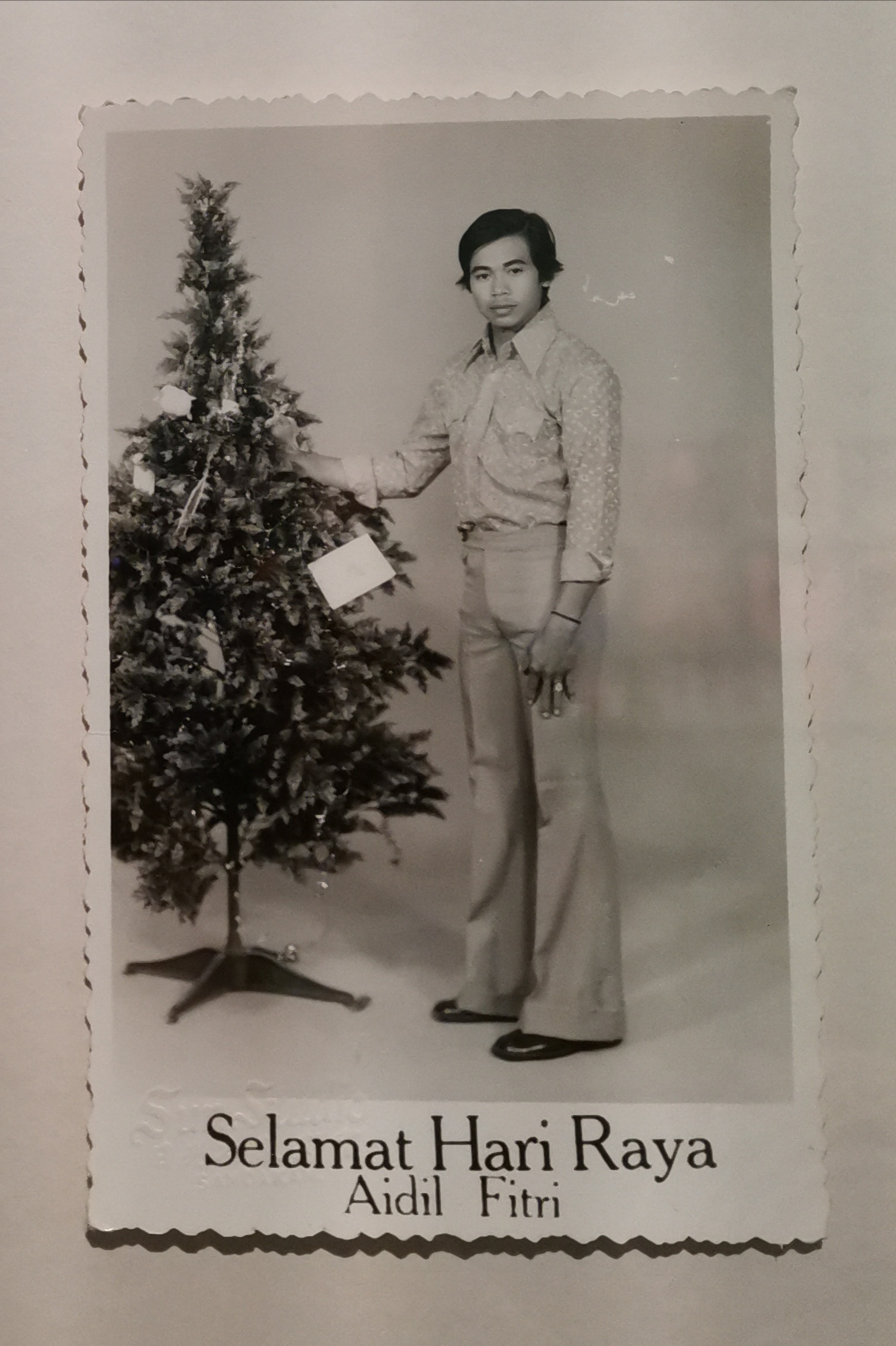

I found myself giggling at a certain photograph that was framed within the walls of the photography exhibition. It was a picture of a man, probably from the 1960s or 70s, standing next to a Christmas tree, with the words “Selamat Hari Raya Aidil Fitri” written underneath. It was such a surreal image to me, as it told the story of a Malaysian past that I have never known.

I had the chance of visiting Kuala Lumpur’s Ilham Gallery exhibition Bayangnya Itu Timbul Tenggelam, which showcased an array of photographs that stretched through the history of Malaysia. Instead of being merely visual historical documentation, the exhibition also illustrated the relationship photography has with the nation’s growing modernity and societal changes.

Upon first impression, I admit that I did not feel that the gallery was trying to convey the artistic nature of photography, nor did I feel that this was an art exhibition at all. In fact, I felt that it was more of an ethnographic showcase of old Malaya and its linked historical events. The text-heavy descriptions around the photographs further emphasised my experience that could best be described as a history lesson, which I wasn’t really expecting.

It also made me think that there was little to no room for the audience to make their own interpretations when it came to observing the photographs. Perhaps because the photographs pertained to Malaysia’s history, it was important for the descriptions to provide the context. However, since it was hard to decipher the images without reading the text-heavy descriptions and learning more about the historical functions of photography, the experience turned out to be more of an ethnographic, history lesson for me. I do not deny that I feel more historically knowledgeable now, but at the time, I felt that the reliance on those heavy-texts somewhat took the enjoyment out of being able to interpret the meanings behind some of the photographs.

But now I would like to take back some of those statements. I realise that the ethnographic nature of these historical pictures was not just a history lesson. After much contemplation, I realise that there is significance in these photographs of the past, which I felt especially with the photos of “Primitive Life” in past Malaya.

The images of “Primitive Life” highlighted Malaysia’s history as a colony of the British, and unsettled me. It was a strange sentiment, to witness the “othering” that these photos had the power of creating.

The images of “Primitive Life” implied a message, or a sense of a colonial ideology, that the first tribes on this land were the “other”, “uncivilized” citizens – as if they were mere objects to be observed and categorised. It felt like history had punched me in the gut.

With that epiphany, I understood the role of photography as a medium that captures “a moment in time” – a term that I explain as the capturing of a live event that holds meaningful significance. The type of significance that I am trying to describe isn’t just limited to what is being shown in the photo, nor to how it relates to the owner of the image. Now I see that there are layers within a photograph that may not be immediately visible to the human eye. Photographs tell a far more significant story of the time in which they were taken, such as the context of the people, the ideologies present, the societal environment and even the state that was in power at the time.

These are elements, or messages, that we would not be able to witness with by just simply glancing at an image. “A moment in time” is what I would use to describe the Bayangnya Itu Timbul Tenggelam exhibition.

That was why I was fascinated with the picture of the man standing next to a Christmas tree, as he wished for a joyful eid in his celebratory postcard – to me, that is “a moment in time” so unrecognisable when compared with our current societal context.

If that same picture were taken in Malaysia today, the image would probably be scrutinised as a subject of online hate. I can only imagine the public’s misunderstanding of his photo, and perhaps the man in the photo would be accused of blasphemy for combining the two religious celebrations into one postcard – an act that was surely meant to convey a multiracial and religious appreciation. It was alarming for me to realise how the values within our society have changed in the course of time.

The image of the man in the 1960s seemed to imply a moment in time that was more relaxed, and more appreciative of the diversity of people in the nation. Why has that changed now? Perhaps it has been the effects of heavier religious policing or maybe it is the creation of social media that has allowed people to freely leave criticisms whilst being shielded behind screens?

Various questions pertaining to religion and multiracial relationships began to spark in my head, all because I had seen a man standing next to a Christmas tree, as he wished for a “joyous eid celebration”. This was a moment in time that I did not recognise in present Malaysia.

From my experience at the gallery that day, such moments in time within the photographs are the most valuable elements to look for in the Bayangnya Itu Timbul Tenggelam exhibition. The images are not only meant to be gazed at and appreciated, but also give us a chance to critically reflect on our present moments. The images are incentives for us to compare, contrast and re-evaluate our society, our ideas and our current state of politics.

Bayangnya Itu Timbul Tenggelam runs until Dec 31, 2020 at Ilham Gallery (Level 5), Jalan Binjai, Kuala Lumpur.

Hamidah Abd Rahman is a writer under the CENDANA-ASWARA Arts Writing Mentorship Programme 2020-2021