BASKL asks a few artists if competition and rivalry in the arts is empowering or detrimental.

By MARIA MURUGIAH

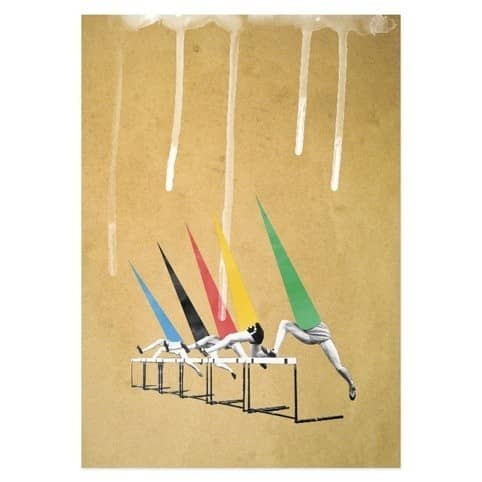

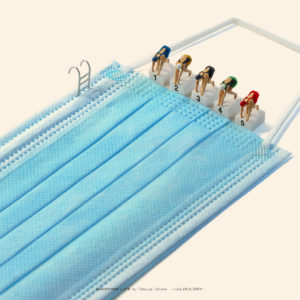

Tis’ the season when we jump up and down in front of the TV, biting our nails and cheering on our dear athletes. Yes, we are right smack in the middle of the Olympics and when we see those three letters “MAS” up on the screen accompanied by the Jalur Gemilang, we roar like the biggest tigers in the jungle!

We’re not the only ones, of course. For decades, the Olympic Games have been a symbol of national pride and athletic dominance.

What if we told you that the Olympics wasn’t always an exclusively sporting tournament? From 1912 to 1948, the Games also featured five categories for the arts: architecture, sculpture, painting, literature and music – each of which was awarded gold, silver and bronze medals just like any other Olympic event! Yes, really.

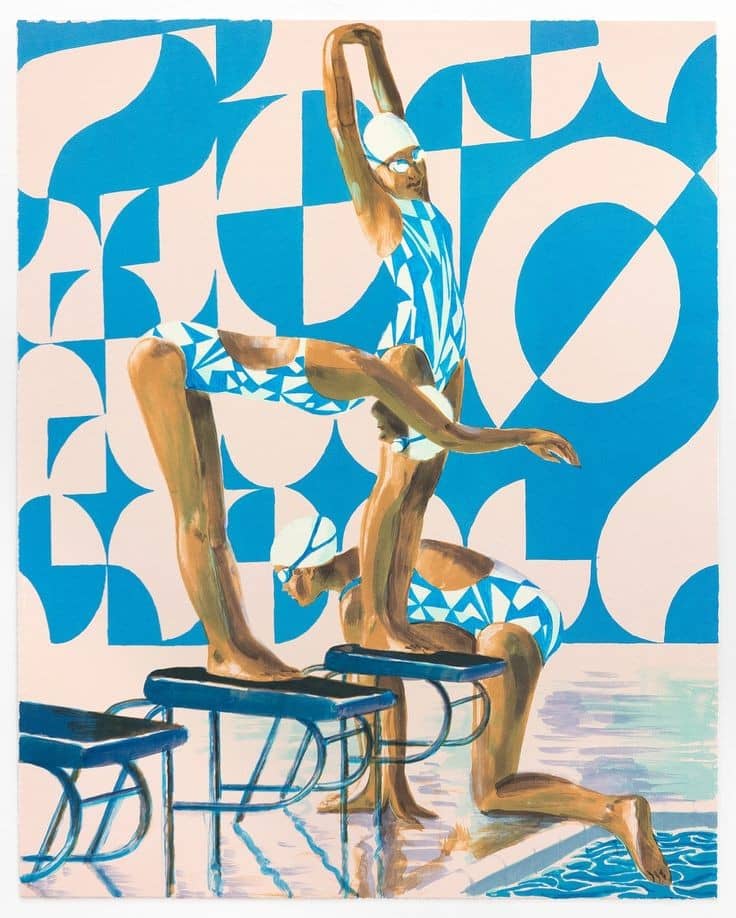

The Art Olympics was the brainchild of Olympic International Committee founder Pierre de Coubertin, who was raised and educated classically, and believed that in order to be a true Olympian, one not only had to be athletic, but skilled in music and literature as well.

It was, in those days of yore, decreed that any artwork presented must be connected to sports, staying true to the Olympic spirit. For example, Georges Dubois of France won a silver medal in 1912 for his model of the entrance to a modern stadium and German composer Werner Egk was awarded gold for his Festive Music for the Olympiad in 1936.

As many entrants as there were, however, even more artists were distrustful and sceptical of the Games.

They didn’t want to be subjected to a win-or-lose situation that could damage their reputation. Also, the fact that the Art Competitions were formulated by those not of the art community was a greater cause for worry. Critics questioned the integrity and true agenda of the organisers.

If KL-born visual artist Izat Arif had lived in those times, he probably would have shared the same sentiment as the sceptics.

“I’m very sure that I wouldn’t have joined the Art Olympics because I think the intention of the Olympics is as a sport and competition. It almost seems that during those times, state-funded art programmes were used as a way to manipulate the public and promote a government agenda.

“I also think the need to ‘be the best’ and to compete in general can be very toxic. Sometimes you make art for yourself, for your loved ones, for whoever. There is no need for competition,” Izat says.

Veteran illustrator Stan Lee, or KULit as he now calls himself, has a different take. Lee is a regular participant of Art Battle – a speed painting competition where 12 artists are split into groups of six on easels set in the middle of a large hall/stadium and given 20 minutes to paint whatever they like.

“Having spent the better part of 40 years working leisurely alone in my studio, it was an exhilarating experience to be thrown into the spotlight, and having to deal with people milling about as well as the need to beat the clock.

“I first went in with butterflies in my tummy. My heart was pounding and adrenaline was flowing. I had practised and planned what I had wanted to do, but when the countdown started, I promptly forgot everything!

“Even with years of experience in the art field, a professional would be reduced to a quivering mass of trepidation if subjected to an arena of a physical competition rather than the quiet, peaceful sanctum of a home studio. The distraction of a crowd baying for blood, the pressure of time and the sight of your opponent feverishly brandishing his weapon of choice is enough to disarm even the most seasoned artist,” KULit says as he recalls his own experience in the art arena.

Lee says that contests like these are a great experience because they force you to get out of your comfort zone, and draw on skills you never knew you had. “You learn to cut to the chase and stop over-analysing, just simplify everything.”

Lyia Meta, a multi-disciplinary artist, says she would have loved to be a part of creating history if she had lived during the Olympic Arts Competitions era.

“Aside from being able to represent your country, which in itself is a huge honour, to be at the greatest event on earth where written records date back to 776 BC would have been surreal!”

Don’t get her wrong, though. Lyia says there should be no competition among artists, as art is subjective.

Instead, she says: “There should be various platforms for art appreciation where emerging and professional artists are given an audience to acknowledge their contributions to the world of visual/performing arts and the changes they have contributed to the artistic landscape.”

Video: YouTube

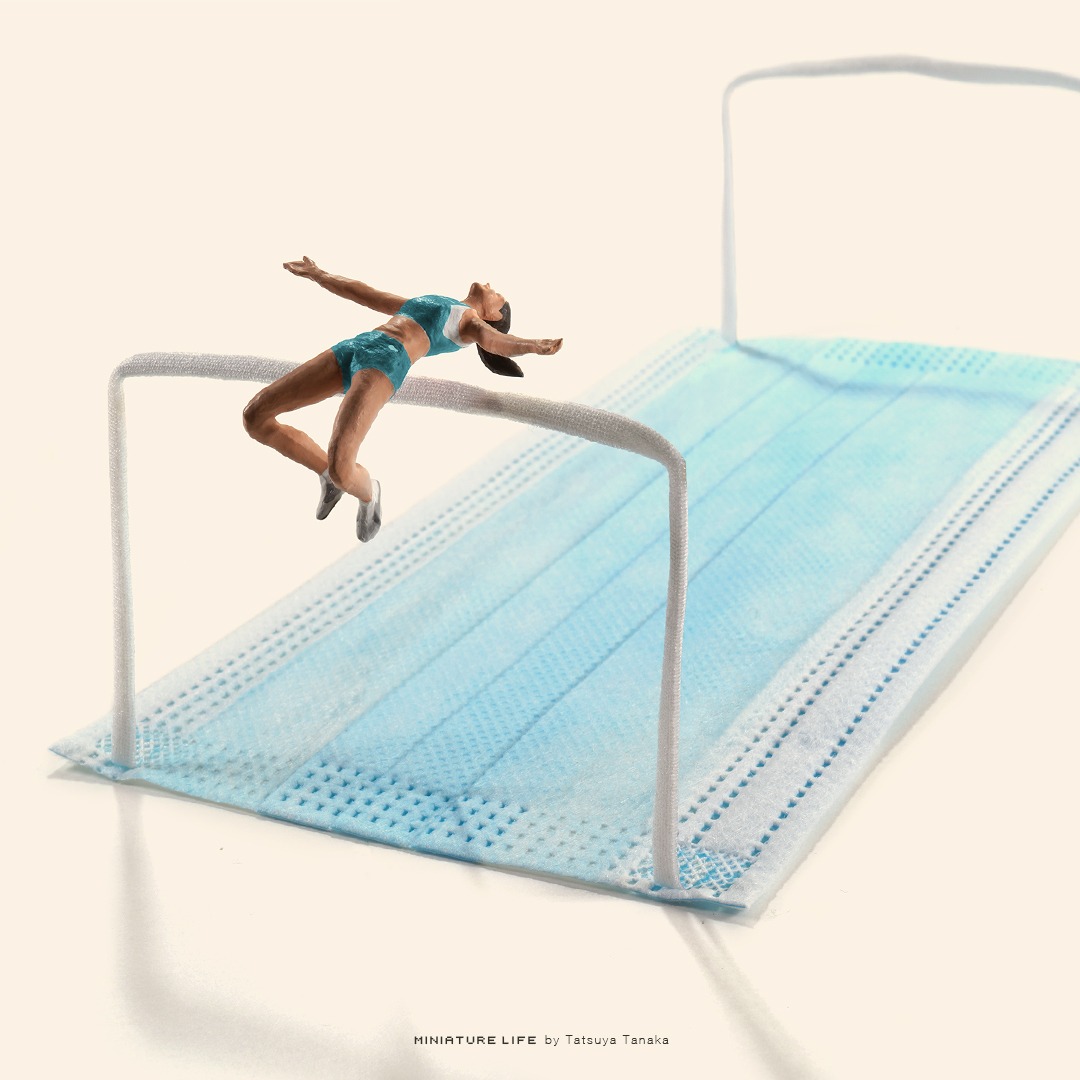

The Olympic Arts Competitions were eventually scrapped in 1948 because technically only amateurs were allowed to participate, not professionals. But somehow the lines between amateur and professional became blurry and there was no way to judge systematically if an artist belonged in the former or latter group.

Izat, whose work has been known to be imbued with wry commentaries on life and art, criticises the bureaucratic structure on which the Olympic Art Competitions were built upon.

“This problem of identifying whether an artist is a professional or an amateur is still present even today. But it seems this predicament only arises among those who do not practise art. It’s ironic that most often the people in charge have no fundamental understanding or formal training of art and yet are in a position of power to determine whether a practitioner is a professional or an amateur.”

If given the chance to revive the Olympic Art Competitions, Lyia would seriously consider it but admits that by doing so things may get a little complicated. When representing the nation, after all, politics are bound to enter the picture.

“And politics and art have never been good bedfellows. Here is where it becomes contradictory, because some forms of art – spoken freely and honestly from one’s heart without prejudice or favour – are considered rebellious forms of expressions.

“And while any form of art requires a certain amount of skill, it is safe to say that skill without artistic direction or expression is not art. So, how exactly would one define excellence?”