An emerging arts professional pens an open letter to legendary Malaysian artist, critic and historian, Redza Piyadasa, giving readers an insight into his approach.

By ELIZABETH LOW for LENSA SENI

Dear Mr Redza Piyadasa,

It is now 2022, and many years have passed since you left us in 2007. Since then, there have been several articles written in tribute to you as your family, and the local art scene, mourn the loss of your presence.

You were one of the giants of the local art scene. A force to be reckoned with, you were best known for your conceptual art and critical writings. Your earlier works such as May 13, 1969 (1969, reconstructed 2006), The Great Malaysian Landscape (1972), and Towards a Mystical Reality: A Documentation of Experiences Initiated with Sulaiman Esa (1974), are only some of your most notable contributions to our fairly new art scene.

But who was Redza Piyadasa, and what do we (the young) know about your legacy? While many of my generation may have heard of your work, we might not have taken the time to understand your approach and outlook as an artist.

To better grasp the essence of who you were as an artist and art critic, I read your MFA thesis in the hopes that it would provide me with a richer insight into who you were.

Reading ‘Art as Art Becomes Art as Art’

Reading your thesis, Art as Art Becomes Art as Art, was nothing short of a riveting experience. This was not only because of your unconventional approach towards art during that time, but also the alternative perspective it offered. Although well backed up with research, as expected from an academic text, reading the typewritten words of your thoughts provided for an intimate experience. One could not help but notice your frequent use of exclamation marks, an indicator of your excitement, conviction and passion for the subject.

Knowing that this was written in 1977 meant that the revelations and opinions expressed in your thesis reflected your methodology in some of your earlier works. In your desire to understand the nature of art, or “art ontology” as you coined it, you explored the logic behind the “visualness” of art as the most significant aspect of the matter. You made the distinction between the “artist-craftsman” and “artist-dialectician” – the former being the maker of artefacts or picture maker, while the latter an aesthetician and investigator of the language of art itself.

The visual outcome and emotive approach of artmaking has largely been a key consideration in the value of art for centuries. It was intriguing to learn from your thesis how you, as a Malaysian artist during your time, were able to challenge that outlook by putting forth a different set of expectations on the role of the artist. That line of thought places art on a pedestal that goes beyond face value, putting more emphasis on the significance of its idea and concept.

Your rejection of the formalistic and stylistic approach to the arts is widely known, but I wonder how it was received by the public, given the landscape of the local art scene of your time. Was it deemed scandalous or absurd? Even today, while many art professionals have adopted a more unconventional approach, preconceived notions of what constitutes art still exist.

Examining works in your thesis show

In the introduction, you highlighted the opinion of critics who felt that the intent of any artwork produced by “visual” artists should be easily conveyed to the audience without the need for wordy text. True to your investigative attitude as an artist, you emphasised the significance of text in your own practice, as well as in the practices of many pioneers of modern art. You further explained this by walking us through your past works which were featured in your thesis show.

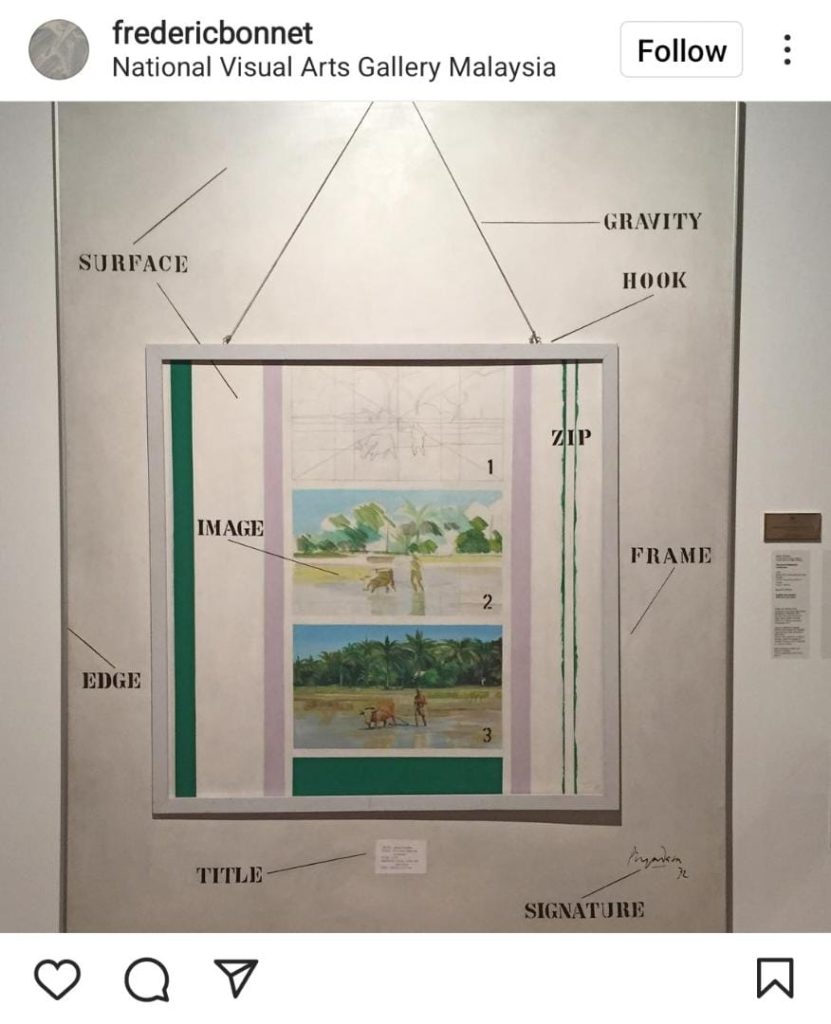

Your entry for the national competition for landscape painting organised by National Art Gallery Malaysia, The Great Malaysian Landscape (1972), displayed an underlying sense of humour and wit. An artwork within an artwork, this painting appears as a textbook study of the Western standard of a traditional artwork. From demonstrating the process of painting a landscape, to clinically labelling the different parts of an artwork, you cleverly highlighted how heavily our approach to art borrows from Western culture – in methods, presentation and perception. What can be seen of your character was your resolve to redefine the context of Malaysian art’s identity and potential.

This line of thought was expanded when you joined forces with Sulaiman Esa in realising the exhibition, Towards a Mystical Reality: A Documentation of Experiences, held at Dewan Bahasa’s Sudut Penulis. Your joint investigation of the character of art and the role of an artist from a non-Western standpoint was radical. The presentation of alternative aesthetics through everyday objects and specimens, which were presented and described in text, made art a vehicle for the memory and presence of a specific time, space and event. The resistance towards the exhibition reflected how deeply ingrained the western model of art was within Asia.

In the 1970s, Malaysia was still a very new country looking to reform its identity and stand on its own, away from the shadows of our colonisers. While the landscape of Malaysian art today has changed drastically since then, your thesis was significant in expressing the thoughts of an artist who had the courage to challenge the narrative of a very formalistic attitude in the art scene. It is illuminating to consider the timeliness of your unapologetically bold ideas and ambitions in your search for the context of art which is essentially Malaysian.

Concluding with parting thoughts

Even today, your philosophy and approach towards art can still be expected to challenge the very basis of the understanding of art for many. It is commendable that you held such high regard for the potential and value of art, for you saw its capacity as a vehicle for ideas, rather than just a beautiful, but empty, vessel.

The newer generations will never truly know you the way your loved ones did, but your thesis gives us a window to understanding the intent and rationale behind your practice. Though you are no longer with us, the conviction and spirit of your character echoes in each sentence.

Signing off with best wishes,

An emerging arts professional

You can read the late Redza Piyadasa’s MFA thesis here. The featured picture on top of this page is courtesy of J Redza.

Elizabeth Low is a participant in the CENDANA ARTS WRITING MASTERCLASS & MENTORSHIP PROGRAMME 2021

The views and opinions expressed in this article are strictly the author’s own and do not reflect those of CENDANA. CENDANA reserves the right to be excluded from any liabilities, losses, damages, defaults, and/or intellectual property infringements caused by the views and opinions expressed by the author in this article at all times, during or after publication, whether on this website or any other platforms hosted by CENDANA or if said opinions/views are republished on third-party platforms.