In memory of the passing of Salleh Ben Joned, BASKL revisited his life and works to understand the unique position that this great maverick occupied in the Malaysian literary scene.

By ATIKAH HANAFI for LENSA SENI

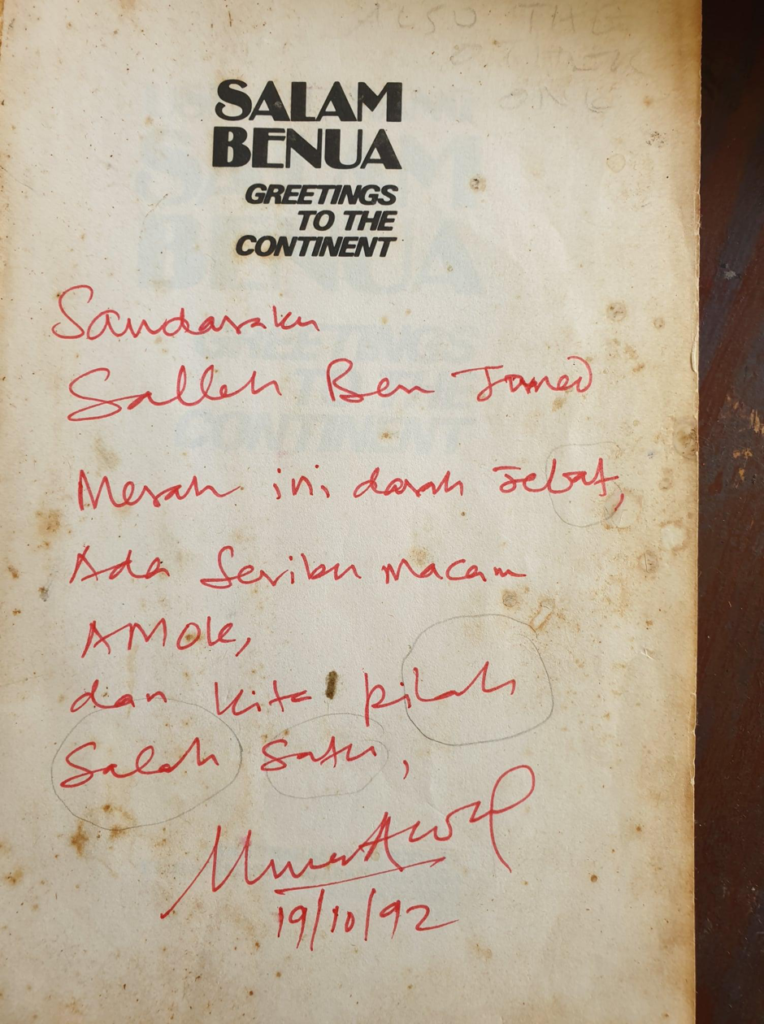

Sajak-Sajak Salleh/Poems Sacred and Profane is the title of Salleh Ben Joned’s first collection of poems, which includes poems written in both English and Malay. A befitting title that could have also been used to describe Salleh as a person. Amidst all too familiar names of Muhammad Haji Salleh, Adibah Amin, Che Husna Azhari and Ee Tiang Hong, Salleh was an oddball of sorts that seemed to walk the literary path in the opposite direction.

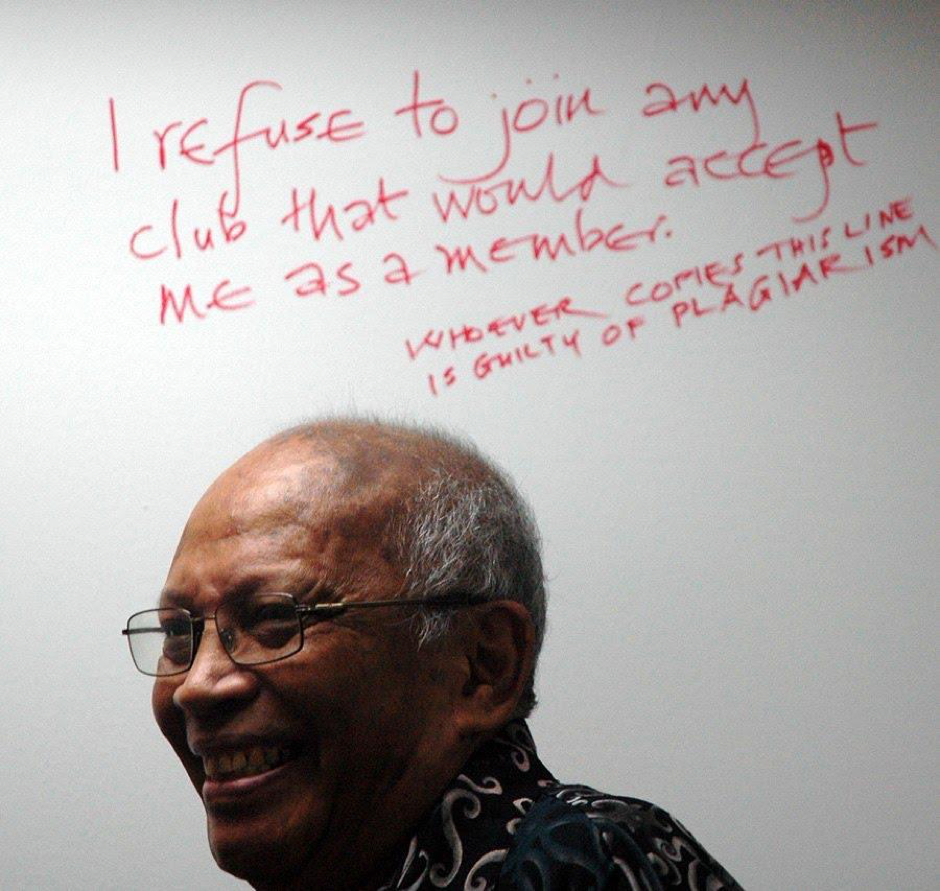

Salleh was a maverick and non-conformist. His works were always provocative, controversial and even vulgar to an extent. One might be taken aback during the initial encounter with his works due to their offensive nature but one might also be amused by his wit and cynical humour. Salleh was an exemplary poet who used his words to ridicule, criticise and question.

A writer, essayist, actor and poet, Salleh was born in Melaka in 1941. He spent several years in Australia as a Colombo Plan Scholar at the University of Adelaide. He then married a fellow student and the couple moved to the University of Tasmania, as their families disapproved of their marriage. It was during this time that Salleh became acquainted with his mentor, James McAuley. In 1973, Salleh finally returned to his home country to become a lecturer in English Literature at University Malaya. He remained there for 10 years until 1983, when he became a freelance scribbler.

Revisiting Salleh’s works and words always brings great insights and lessons. Here are some thoughts that struck us about this great maverick, as we re-read his poems and words.

Salleh wrote remarkably well in both Malay and English

Although he is most known for his poems in English, which have contributed significantly to the corpus of Malaysian literature in English, Salleh also wrote eloquently in his native language. It is not so far-fetched to say that some of his Malay poems possessed graces and nuance that surpassed some of the great poets in the Malay world during that time.

This opinion was also championed by Faisal Tehrani, who, while writing a tribute to honour this poet’s passing in Malaysia Now, stated that “behind such provocative messages and themes, the poems he wrote in the national language were very beautiful, delicate, full of metaphorical spirals and powerful images.”

Nevertheless, one of his best Malay poems drew its power, not in terms of a rather flowery and romantic use of language but its sheer simplicity and matter-of-fact messages. In Malayaku, he reflected on the names of places throughout Malaysia:

Aku Amat rindukan:

Tanjong Penawar

Kampong Seronok

Rantau Abang

Janda Baik

Gertak Sanggul

…

…

Aku lemas dan layu di tengah-tengah

Petaling Jaya

Damansara jaya

Desa jaya

Ampang Jaya

…

…

It is interesting how Salleh observed the disparity between names of more rural and outskirt areas versus the ones located in the more “affluent” side of the country. While stating his longing for all these small towns and villages, Salleh also highlighted the rich vocabularies used in naming these places in all their colour, flavour and glory. This scenario was a stark contrast to the common and boring district names in the city.

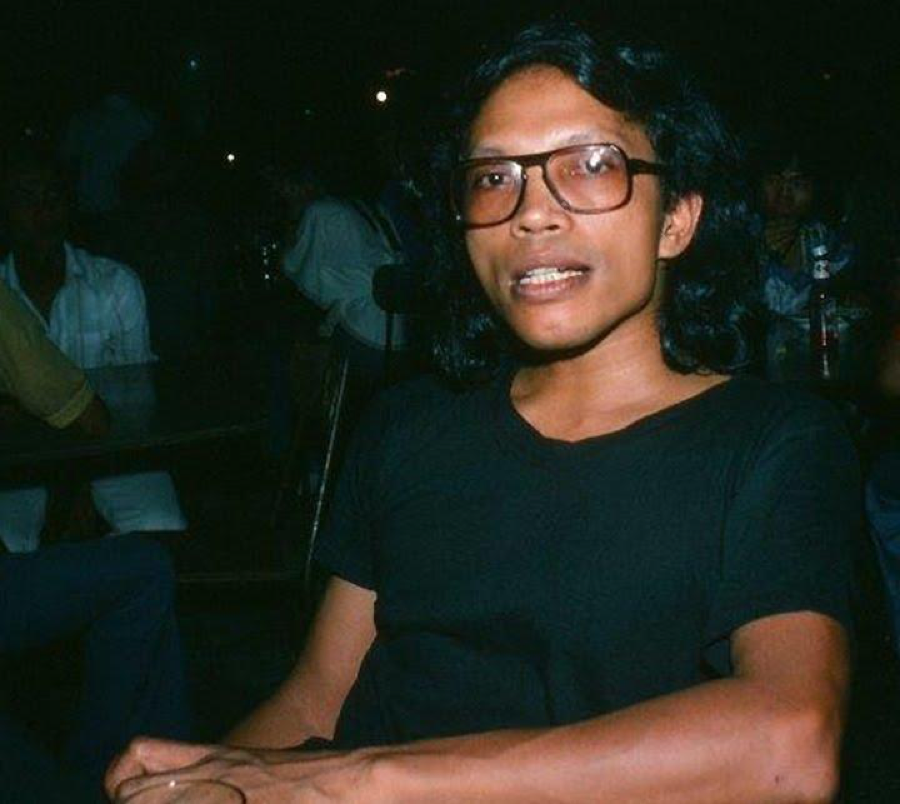

Photo: Salleh Ben Joned’s Facebook

The unwavering pursuit to question

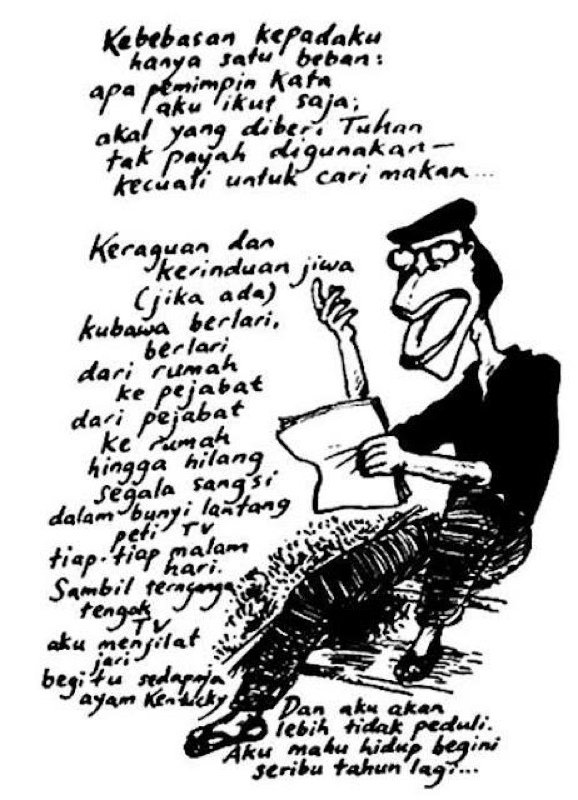

Profanity permeates Salleh’s poems. His explicit use of vulgar language, profanity, blasphemy and sexuality in his poems and essays situated him in a unique position in Malaysia’s literary world.

His nonchalant and unapologetic way of criticising behaviour and other sensitive topics was prevalent in many of his works. Salleh deliberately transgressed the religious, cultural and political boundaries through his writing. Often with great sacrilege, he caused discomfort among many readers, writers and critics. So much so that Muhammad Haji Salleh declared Salleh’s debut poetry collection as “the most traumatic experience for the Malay literary scene”. Salleh responded, “If with just one book, my first, I’ve traumatised the Malay writers, I wonder what the next one will do!”

He also mischievously ended his Preface in his next collection of poems, Adam’s Dream with a statement, “I hope my Adam’s Dream won’t become their nightmare.”

Championing the rojak culture

At one point, Salleh stopped writing in his mother tongue. Perhaps one might say that this decision was in reaction to the earlier commentary by the national laureate. Yet, Salleh was not one to be easily offended by the snide remarks of his peers. Most often, he was the one who did the offending.

It was none other than an act of rebellion. In the late 1970s and 1980s, Malaysia made its move to elevate the status of the Malay language as the national language and medium for national literature. This policy, however, pushed aside Anglophone writers of his time. Salleh became one of the very few who refused to comply, and from that moment onwards, he wrote mainly in English.

Throughout his life, Salleh never ceased to emphasise the power of arts as a means to destabilise the status quo. He always championed the idea of “rojak” culture as a part of Malaysian identity and the importance of owning the languages that one speaks.

Through his column in The News Straits Times “As I Please”, Salleh argued, “English was playing and would continue to play an important role not only in our relations with the rest of the world but within our own multi-ethnic society. And that role is by no means merely economic, scientific or technological.”

He further added, “A language belongs to those who speak it. It’s as simple as that. Given this fact, and that language communicates experience and is capable of transcending the boundaries of the culture of its origin – given all this, then the English we speak in Malaysia today belongs to us. It’s our English; along with BM it expresses our ‘soul’, with all its contradictions and confusions, as much as our social and material needs.”

Salleh Ben Joned left us at time when Malaysia was still battling the COVID-19 pandemic. In the wee hours of Oct 19, 2020, Salleh died of heart failure at his home in Subang Jaya. He was 79 years old.

Following his death, many tributes have been written in honour of his memory. Among the most memorable was one made by Zan Azlee, a Malaysian filmmaker and journalist: “If there ever was a Malaysian Zack de la Rocha or Widji Thukul, then in my eyes it was Salleh Ben Joned.”

Rest in power, Salleh Ben Joned.

Atikah Hanafi is a participant in the CENDANA ARTS WRITING MASTERCLASS & MENTORSHIP PROGRAMME 2021

The views and opinions expressed in this article are strictly the author’s own and do not reflect those of CENDANA. CENDANA reserves the right to be excluded from any liabilities, losses, damages, defaults, and/or intellectual property infringements caused by the views and opinions expressed by the author in this article at all times, during or after publication, whether on this website or any other platforms hosted by CENDANA or if said opinions/views are republished on third-party platforms.