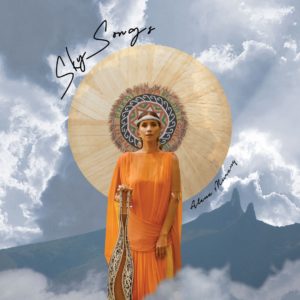

A descendant of the Dayak Kelabit people of the Baram river in Sarawak, Alena Murang has released an intriguing new album called 'Sky Songs'.

You’ll have heard already, and probably caught a glimpse of some stunning video footage and photography promoting Alena Murang’s new album, Sky Songs, which was released in May just in time for Hari Gawai.

The Kuala Lumpur-based recording artist who is of Kelabit/Anglo-Italian descent has been steadily building a following for her unique sound, performing at music festivals around the world, earning accolades, including an award in March 2021 from the Sarawak government in recognition of her contributions to indigenous music.

A follow-up to her 2016 EP Flight, Sky Songs features four songs in the Kelabit language, one song in Kenyah, two instrumental tracks and an English song. With the new album, Alena has expanded her sound and gone beyond sape music with which she is most associated.

Alena, her producer Joshua Maran and bandmates Jonathan Wong, Herman Ramanando, Jimmy Chong recorded the album over the course of the pandemic – no mean feat. The collab has resulted in a fresh sound which you’ll hear on the new album.

“I wanted everybody to bring their own self, sound and experiences to the album. The band comes from lots of different disciplines – rock, celtic, traditional Chinese, R&B. Growing up I listened to a lot of rock: Limp Bizkit, Offspring, Third Eye Blind. My dad and uncles listened to a lot of American folk and country music. So you’ll hear a lot of those influences too.”

Here, Alena reflects on her desire to share stories which are a part of her community’s heritage, in a contemporary way, with the world today.

How do the themes on Sky Songs relate to today’s society? Where and how does the average person on the street connect with it?

We all have roots and heritage and I like to think that people can relate to Sky Songs through their own roots and heritage. I think that a lot of us have been disconnected with heritage. But I don’t expect people to relate through the lyrics because only one of the songs is in English, while others are in Kenyah or Kelabit which even I myself am not fluent in. But I figured if we see people here loving the song Despacito without even understanding the lyrics, then why not. The tracks are influenced by mainstream genres like rock, pop and folk, and I think the average person can appreciate the music just as music. To be honest, we just create from the heart, we start with a story or a concept, and we write songs that we want to write …

What did you learn from Flight which you were able to apply in Sky Songs?

Flight was my first album in 2016, with that album our intention was to keep it as close to the roots as possible. We very much focused on traditional sape music and traditional singing. Since then I have grown a lot. These songs are all written with my producer/cousin Josh and we’ve both grown as people and as musicians since then. I think it’s just natural for that to show in Sky Songs, five years later. I’m also working with a band now. So yeah, that growth and development and the personalities of each of us is reflected in Sky Songs.

Given the nature of how albums are put together these days, is Sky Songs more a collection of singles as opposed to a thematic collection of songs?

Not at all. We consciously wanted an album … we thought about it. I know that it’s more common to release singles these days but I wanted it as an album. I like the idea of telling stories and to have that collection of narratives. One of the premises of Sky Songs comes from the Sunhat (Sunhat Song). The Sunhat is the image you see behind me on the album cover. It’s a big hat that we wear in the farms to protect us from the sun. And in the past, we see this recounted in some of our very old songs, when the sky was likened to a sunhat, and all earthly creation lay underneath it. And the sky was called a sun hat dome. Every song on the album has a theme linked to the sky: Gitu’an, for example is Kelabit for stars. The song came about when we were learning about the stories of our great ancestors, Tuked Rinih and his wife Aruring Menepo Bo, who lived in the skies and travelled to Earth via a great waterfall. Although our lives are very different now and the Kelabit community at large practices a different set of belief systems, the community values (togetherness, looking after each other) and the things we valued (rice, beads) are still the same as today and very much grounds us in our identity. We are who we are because of those that came before us.

Maya’ is about the cool breeze bringing something that sounds so familiar; there’s a song called Thunder In The Moon which is about the different sounds that the thunder makes and that’s quite typical of our traditional lakuh where we sing about different sounds of thunder, and likening it to a story.

How does all that oral history – everything you’ve learnt from your elders – emerge in your songs? At which point in the process does it get the Alena treatment, and how does that manifest in the end product?

Our input is a lot of oral history and stories. I kind of make myself a vessel for those stories. And when those stories come to me, I also make sense of who I am in this time and in this space, and I think that’s where they get the Alena treatment. We, as a community, don’t expect our songs to be static in one moment. Even when my grandmother sang songs, she would sing it different to how her mother and her grandmother sang it. I think we take these stories as inspiration and also kind of informing what we write. Usually when I receive a song or a story, I take a while to sit with it, to learn it, and to reflect on what it means to me. This can take up to two to four years, and then I speak to Josh and we develop it into a song. Sometimes I come to him with an emotion or situation that I imagine for the song and then we write the song. You can say it’s an inward process, we really dig deep in order to create.

What have your learnt from the elements? How do the rock, tree, mountain, bird, rhythm, and melody speak to you?

I can’t describe it directly. I feel very connected and grounded when I am in nature. And I take those feelings. For example with the song Maya’, I had this imagery from recalling an experience in my head of being back in the village on a mountain overlooking this expanse of rainforest, and feeling a very gentle, cool wind. When you feel that cool wind you just get a feeling that’s so familiar with where you are and who you are. You feel so comfortable. I think it’s such experiences in nature that give me clarity to create.

How do you tap into your emotions to guide your lyrics? Are you only drawing from tradition or various other sources, too?

We tap into tradition for sure. But the context of who we are now – contemporary, modern, city-dwelling musicians like many others – that also informs us. The biggest difference is that I don’t write love songs, or hate songs or hating on your ex songs. I don’t really sing about romantic relationships. My emotions are quite nostalgic and guided by the heritage and the stories we want to tell. I write from the heart, and I am quite an emotional person.

You could have taken any number of musical routes, yet you chose to honour your tradition by making music very close to your roots. Why?

It’s very interesting … it chose me. I didn’t choose it. I actually wanted to be a painter and never in a million years thought I could be a musician. I grew up learning classical guitar, saxophone, sape and dance and really enjoyed it but never saw myself as outstanding or exceptionally talented. But somehow all the things I have done have just led me back to sape and singing. And I just had to follow where my dreams were taking me. That’s how I ended up here – it’s been a very organic journey with music.

What are the barriers for an artist making music like yours?

My music doesn’t really fit in into mainstream music. Gobally, world music it’s a niche market but in Malaysia, it’s very, very small. For world music, one needs very specific agents, managers, media, because there’s always a very strong cultural story and social causes linked to it. So it’s been tough in Malaysia. Before Covid, I was travelling and playing a lot overseas and that helped me to develop my international market (Alena has played at festivals like South by Southwest in the United States, Førde Traditional and World Music Festival in Norway, and OzAsia Festival in Australia).

It’s hard being a musician in Malaysia. And it’s even harder being an independent musician in the world music industry but I think I’ve been able to develop and carve out that niche to my advantage also.

For more on Alena, check out her official website.