At The Back Room last year, Hoo Fan Chon’s exhibition explored the various disparate interactions around a Chinese banquet meal, going beyond the dining table, from the trivial acts of descaling a fish, to the declaration of one’s financial and social status, and the experiences that stay with us after the meal.

Story and photos by WILLIAM CHEW for Lensa Seni

How we eat together has a performative aspect that takes on different forms depending on the occasion. Eating with loved ones can be simple yet intimate. A feast with an extended family would be festive, filled with intense laughter and banter, maybe even some arguments. But a dinner involving a business deal calls for extravagance, lavishness and overabundance, to butter up potential clients.

Late last year, at The Back Room, Hoo Fan Chon’s exhibition, The World is Your Restaurant featured seven pieces of works with a range of mediums including photography, acrylic and mixed media paintings, digital animation and physical installations. Together they explored the various disparate interactions around a Chinese banquet meal, going beyond the dining table, from the trivial acts of descaling a fish, to the declaration of one’s financial and social status, and the experiences that stay with us after the meal.

Fish are a familiar subject for Hoo, as found in two of his previous works, My Earthiness, Your Tenderness (2018) and Bermimpi Demi Negara (2019), where he examines the intersection between memory, history and places. These topics are tied to his childhood, growing up in a fishing village near Klang, and spending time with his father, a fisherman, who would occasionally treat the family to the lavish banquets upstream in Kuala Lumpur.

Looking through the glass doors of the gallery, a red picture frame caught my eye. Titled Family Album, this piece features family photos cropped into identical elliptical shapes, arranged in an elliptical manner, as if to draw parallels between these memories and the dishes on a table. The photos are tiny which placed me in a dilemma of wanting to get a closer look, and being slightly embarrassed for prying into someone else’s private life. Each photo showed a snippet of a big family dinner. Moving my eyes through them, I could imagine the clatter of utensils, the cheers at the grownups’ table and the chatter at the kids’ table. Amidst all the noise, the photo in the middle was of a family, presumably Hoo’s, enjoying a day out at sea.

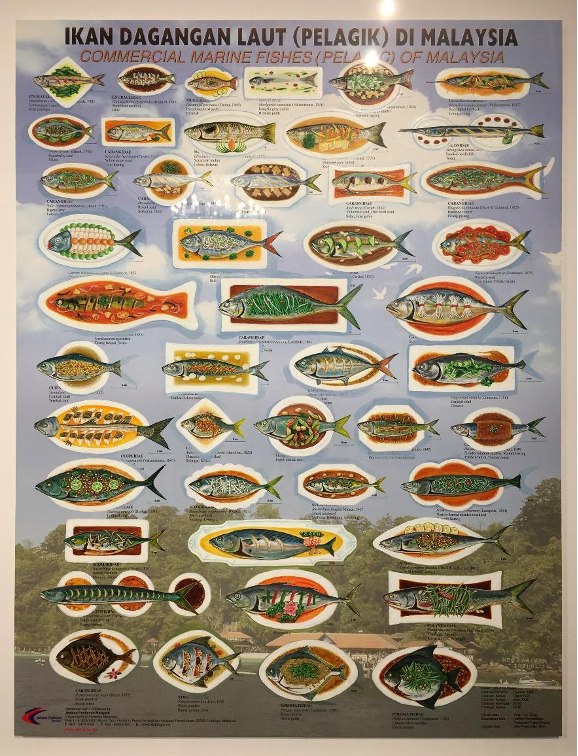

Hanging next to the family album was a poster of fishes titled, Commercial Marine Fishes (Pelagic) of Malaysia. This was originally issued by the Department of Fisheries Malaysia categorising the different species of fishes found in our seas. Here, the artist toys with reality and memory by painting over the factually illustrated fishes with a speculation of how his late father would have prepared them as dishes on plates: the ingredients that would have been used, how the fishes should lay on the plate, and even specifying the shape of the plate. Relaying the artist’s intention, gallery sitter Umar explained that this playful piece offers a way to shift our scientific view of the natural world into a more cultural and gastronomic one.

The star of the show, The World is Your Restaurant, was a reproduction of a table set for a fancy Chinese banquet, located in a nook at one end of the tiny gallery. Lights, tablecloth, utensils, folded napkins, and even the appetiser peanuts were all set and ready for a meal. This was accompanied by Seafood Tools for the Sophisticated Home Chef, a series of three circular acrylic paintings, each featuring a different seafood being prepared by a pair of hands using specific tools that the artist found being sold online during lockdown. The compositions were reminiscent of Chinese embroidered fans, where the canvases are circular, subjects are cropped up close, and perspective is flattened.

At first glance, it was a rather perplexing installation, there were many things to be seen, but nothing much to be said. After all, what’s the difference between being here and being in an actual restaurant? Having walked around the table a few times, and still not ‘getting it’, my mind began to wander.

I was reminded of Ang Lee’s Eat Drink Man Woman (1983) and Wong Kar Wai’s In the Mood for Love (2000), the kind of food being eaten and how the characters ate together played an important role. They helped the audience relate to the complexities of interpersonal relationships, be it the drifting apart of a traditional family or the yearning for a temporary comfort in place of an absent spouse.

The almost ritualistic nature of a Chinese banquet, with its thousand and one rules of what to do and what not to do, often leads to a predictable dining experience. Relatives and old friends celebrate their achievements, reminisce about the past, and end the dinner by arguing about who foots the bill. But it is also because of its typicality that any difference from the norm becomes memorable. (Here, I was thinking of a dinner where I enjoyed the refreshing stories from a cousin I have not met in years, and that awkward one where I sat with unfamiliar faces silently for too long.)

The title The World Is Your Restaurant also reminded me that this type of restaurant is not just limited to Malaysian Chinese, but also to those away from home. When living abroad, there are mediocre restaurants which we can’t help but keep going back to, not because there are no other choices and certainly not for the quality of their food, but rather for the atmosphere of their interiors. The kitschy ornaments, wallpaper, chandelier and dated furniture, much like in this installation, are so typical that they recall just about any other restaurant back home – good enough for the homesick!

Snapping back to the present, the table was still there with everything in its place, napkins folded, bowls on plates and chopsticks to the right, waiting for the next visitor to have a meal. But unlike being in an actual restaurant, where so much life is happening, here there was stillness.

This exhibition was a curated display of Hoo’s memories, it was not a realistic depiction of a Chinese banquet. Hoo’s memories formed a common space, onto which our own memories and imaginations could project. Upon leaving the gallery, I overheard a group of visitors sharing their own dining experiences, and an illuminating realisation came to me, that a Chinese banquet should never be enjoyed alone.

William Chew is a participant in the CENDANA ARTS WRITING MASTERCLASS & MENTORSHIP PROGRAMME 2021

The views and opinions expressed in this article are strictly the author’s own and do not reflect those of CENDANA. CENDANA reserves the right to be excluded from any liabilities, losses, damages, defaults, and/or intellectual property infringements caused by the views and opinions expressed by the author in this article at all times, during or after publication, whether on this website or any other platforms hosted by CENDANA or if said opinions/views are republished on third party platforms.