The Penang Art District (PAD) is an initiative by the Penang State government to unify the local arts scene and spur its economic growth.

By MIRIAM DEVAPRASANA for Lensa Seni

Since its selection as a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 2008, George Town has received greater global recognition and appreciation for its arts, culture, and heritage – it is the epicentre of Penang’s creative economy. The local government has since acknowledged these fields as complementary to tourism and as key assets for economic development.

As a result, arts and culture in George Town have become more accessible through events and installations designed as tourist attractions. These include annual events such as the George Town Literary Festival (GTLF) and George Town Festival (GTF) which have emerged as prominent art festivals in the region, featuring international and local art practitioners and their work. To bridge art to the island’s mainland counterpart, the Butterworth Fringe Festival (BFF), offers a similar framework of activities.

While these festivals have elevated Penang’s status, they have, more importantly, provided annual avenues for select local artisans and performers to showcase their work. Riding on the coattails are traditional art forms such as the Wayang Kulit, Boria, and Ghazal, supported as a way to promote and conserve our intangible cultural heritage.

However, when the stage lights dim and the curtains close, one question lingers: where are the arts in the inner city?

Sure, there are the installations of floating umbrellas and LED stars, or iconic sculptures from all over the world. But what about the art that informs us of our histories and shared identity? That which is unique to Penang. Art that is cultivated and sustained by, and for, Malaysians – not treated merely as a commodity.

Any hint of an answer is like striking gold. Yet, there exists a paradox – a small-scale, thriving, yet dispersed and fragile arts scene within this small heritage city.

George Town’s Art Scene

Penang’s creative economy receives very few resources and only some support from the federal or state government, especially in terms of infrastructure, facilities and funding. The local arts scene is largely dependent on private investors, collectives, arts communities, and privately-owned spaces which work largely in silos.

One example is Hin Bus Depot, a cherished creative community hub established in 2014, dedicated to supporting arts practitioners through innovative business strategies. Despite having private investors, one of its biggest concerns is financial sustainability.

Financial instability was also one of the main reasons for penangpac’s closure earlier this year, which led to a loss of a creative hub and a venue with state-of-the-art facilities for Penang’s arts communities. This is especially felt by students from the School of the Arts, Universiti Sains Malaysia who would intern at penangpac, and local theatre troupes who now resort to using multipurpose venues with limited facilities to stage productions.

While arts communities struggle with these realities and could do with more sustainable mechanisms of funding and arts visibility, the state’s tourism institutions have accentuated street art as its cultural, creative and artistic fix. Tourists flock to Armenian Street for a photo-op with Ernest Zacharevic’s mural, “Children With A Bicycle”, or to “Umbrella Alley”. Few walk into the local hub of grassroots artisans just across the street; fewer still leave with a purchase.

Just down the road is Tan Kok Oo, a heritage practitioner of Nyonya beaded shoes, who has found that people no longer appreciate the art and value of beaded shoes. To sustain the business, he now offers a contemporary clothing line, gifts, and souvenirs that eclipse any vestige of Penang’s once celebrated heritage.

This is the unspoken reality of Penang’s creative economy – one where art that serves as tourist attractions and quick economic gain surpasses the value of cultural arts, pushing them and their practitioners further out onto the peripheries of the fragile and dispersed local arts scene.

Penang State Government Offers a Remedy

To unify the local creative economy and spur its economic growth, the State government proposed a project called Penang Art District (PAD). Initially launched in 2015, Siaboey Reborn: Penang Heritage Arts District was intended to regenerate and revitalise the area known as Sia Boey through preservation of the historic Prangin Canal, restoration of shophouses for art galleries, studios, schools, and workspaces, and the conversion of the 19th-century Prangin Market into a hawker food court. Headlines accorded that the pièce de resistance would be a world-class privately funded public art museum – the first of its kind in Malaysia.

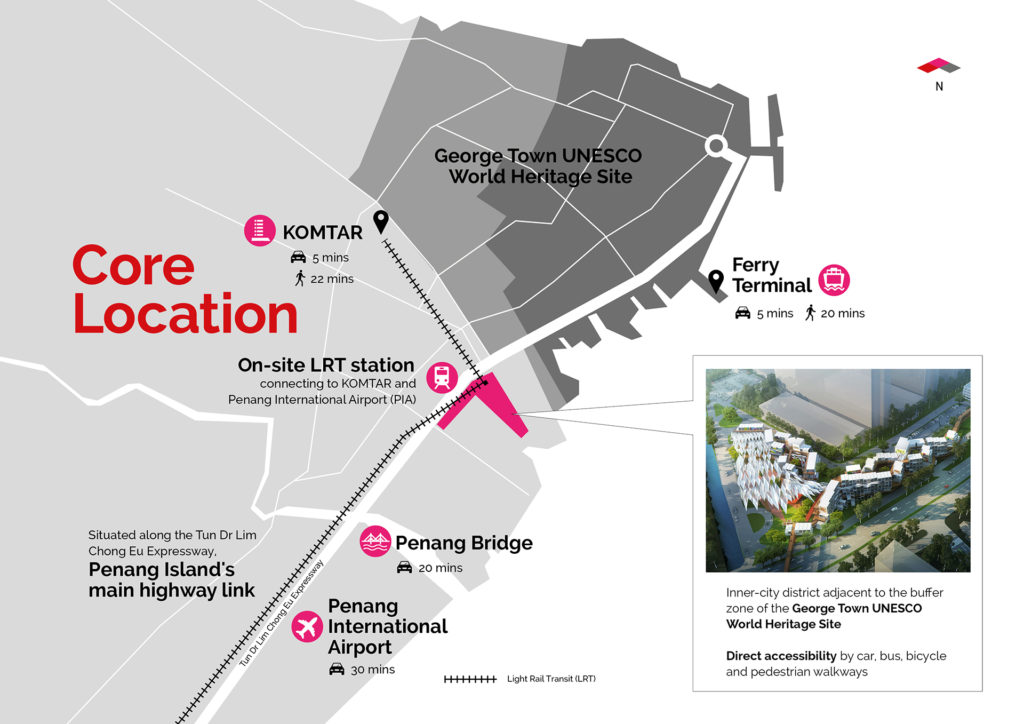

Six months later the area was redesignated as a transportation hub for the planned LRT and MRT interchange lines.

Needless to say, this was met with much controversy and local arts and cultural communities expressed their disappointment. Local activist Khoo Salma commented: “The dream of an international urban art-park has turned to dust”.

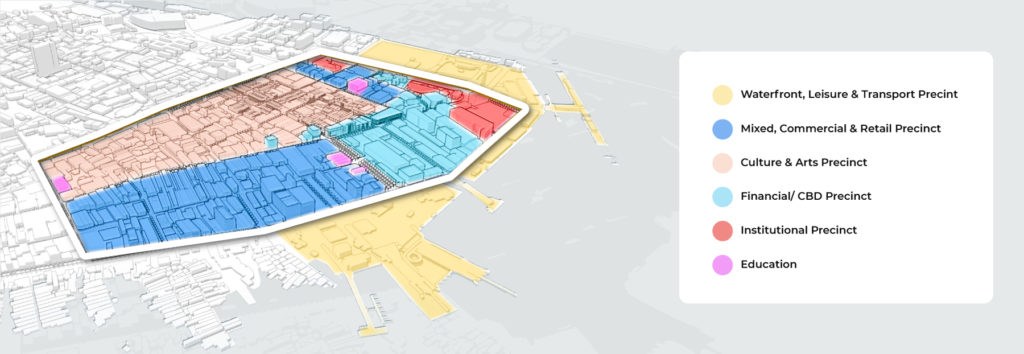

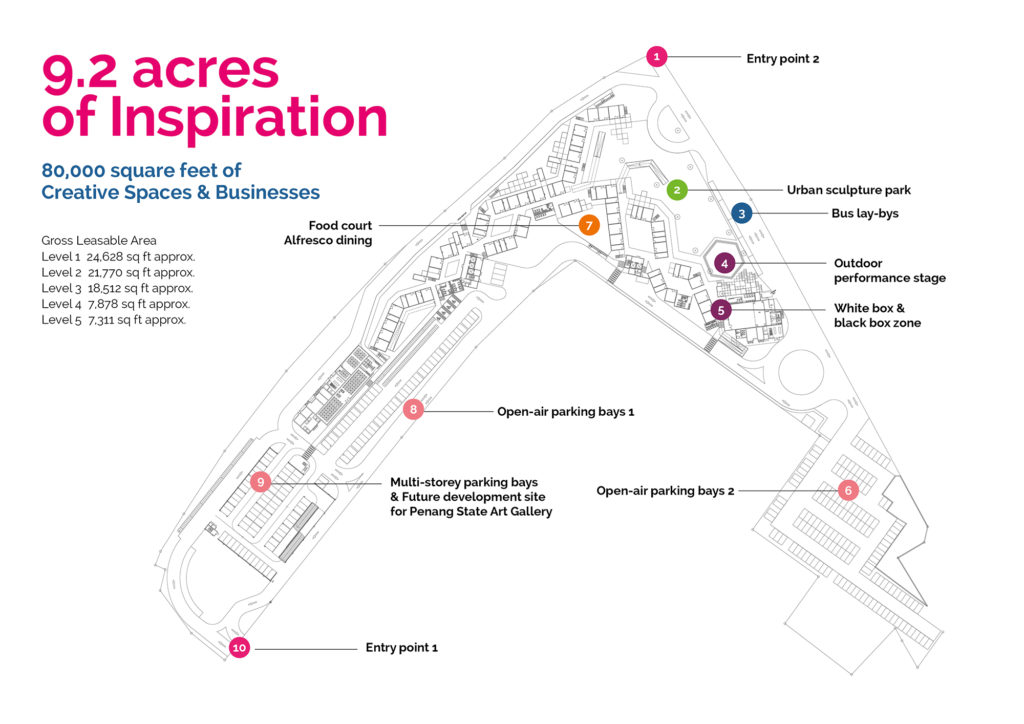

PAD was then relocated to a vacant plot of land just beyond the outskirts of the inner city, with a new artistic vision – a 100,000 sq. ft. built-up space of mainly cargo containers to house the “single largest collection of art galleries, cultural museums, exhibition spaces, arts and music studios, art schools and workshops in Malaysia”. Construction plans are projected to begin in 2023.

While it may sound good on paper, the PAD proposal falls short in capturing how it will maintain and develop the existing diverse creative economy. Beyond the frills of its vision is the intention of capitalising on art for tourism and quick economic gain. It will be an attraction with no logical connection to the existing arts community in the inner city. Therefore, although it claims to be complementary, it will threaten the already vulnerable and tenuous arts scene in the inner city.

PAD is a top-down approach with very little engagement with the needs of local arts practitioners (and an unhealthy obsession with shipping containers). It is a mirage for arts visibility, with little consideration towards developing and establishing a more tangible and essential creative hub with mechanisms to support, stimulate, and foster vitality.

What George Town’s Arts Scene Needs

There are a myriad of aspects that need to be deliberated to foster George Town’s creative hub. This includes critical arts management, a functioning funding mechanism and capacity building, among other things. These require a redirected focus on long-term plans by key players such as the Penang State EXCO Office for Tourism and Creative Economy (PETACE), George Town World Heritage Incorporated (GTWHI), and Penang Art District for significant change in Penang’s creative economy.

One major step in that direction is to create more spaces to increase art visibility within the inner city.

Although there are several smaller, multipurpose events spaces, there is a far greater need for more accessible venues for arts practitioners to engage, install, present and perform their work. The limited facilities of institutional spaces have resulted in a high dependency on privately-owned and managed spaces for events and performances.

If the State wants to seriously develop the arts and culture sector, it should start adopting policies and means of negotiations with the different arms that own or manage the abandoned buildings and old warehouses within the inner city. These can be repurposed and readapted into spaces with appropriate infrastructure and facilities which support the local arts ecosystem whilst simultaneously bringing life into these old buildings.

Alongside that, the State needs to revisit the issue of unregulated rent within the heritage zone. Grassroots artisans, for example, are wholly dependent on independently owned and/or managed shophouses to display and sell their craft. Depending on the size of their display space, and location of the creative hub, each artisan spends an average of RM1800 on rent – an unfeasible amount for grassroots artisans trying to grow and sustain in the industry. Despite being a concern highlighted in 2016, little is known whether appropriate measures have been taken to tackle the issue.

Finally, the state’s institutions need to start engaging and investing in all forms of its creative arts industries, and not just promoting street art as cultural representations and expressions of Penang. This includes looking at activities and events beyond annual festivals which are currently the primary avenues for traditional art forms and the performing arts. Agencies related to these initiatives should look into providing increased resources and support to ensure that all forms are made accessible to the public for a more balanced and healthier arts ecosystem.

With Penang’s creative economy grappling with the aftermath of the pandemic, its exposed vulnerabilities are likely to remain, post-Covid. The inner city carries a huge potential to develop its creative hubs, and eventually becoming a fully-fledged creative city, but only if the local government fully understands and highlights the needs of Penang’s creative sector in its policies.

The State, therefore, needs to seriously reconsider PAD, take critical measures, and redirect its ambition towards rebuilding and strengthening the fragmented foundation of Penang’s creative economy. Otherwise, the art district risks becoming an incubator for an exclusive community of art consumers while existing local creatives struggle to grow in an under-developed, underappreciated, and unsustainable arts scene.

Feature photo is of the public art installation of iconic landmarks and monuments from around the world at Esplanade, Penang to boost domestic tourism, taken by Muhamad Amir Mersyad Omar for Buletin Mutiara.

Miriam Devaprasana is a participant in the CENDANA ARTS WRITING MASTERCLASS & MENTORSHIP PROGRAMME 2021

The views and opinions expressed in this article are strictly the author’s own and do not reflect those of CENDANA. CENDANA reserves the right to be excluded from any liabilities, losses, damages, defaults, and/or intellectual property infringements caused by the views and opinions expressed by the author in this article at all times, during or after publication, whether on this website or any other platforms hosted by CENDANA or if said opinions/views are republished on third party platforms.