Review by LILY JAMALUDIN

Anurendra Jegadeva’s latest for Wei Ling Gallery, in Brickfields, Kuala Lumpur, is a collection of works created under lockdown. It’s a vast collection that considers global themes ranging from migration, empire, democracy, capitalism, to, of course, the ongoing pandemic. Much like the rest of his body of work, Anurendra’s acute reflections on history and politics continue in Scream Inside Your Heart.

Still, what strikes me most about this exhibition is not so much its vastness, but its consideration of the small and personal in contrast to the grand currents of history. There is no unexamined life for Anurendra. The self-interrogation and tender personal observations of family, as the artist attempts to make sense of the global turmoil and failed leadership exposed and exacerbated by COVID-19, is what makes this exhibition so memorable.

One of the pieces that kicks off the exhibition is Same Old Story. It’s a triptych with a portrait of the artist’s daughter (a frequent subject in the exhibition) sandwiched in between portraits of policemen from the American Black Lives Matter protests and the Hong Kong security laws protests. This is one of the biggest themes of Scream, as well as one of the struggles much of us experienced during lockdown: being sandwiched inside a world going through violence, extremes, and passionate struggles for democracy – while still, life goes on.

The exhibition’s title was inspired by a Japanese video of two businessmen who remain completely still through a rollercoaster ride. At the end of the ride, they turn to the camera and whisper, “scream inside your heart.” This is the spirit of the exhibition: the sense of being on an unstoppable rollercoaster, immobilised as the world around us changes rapidly.

An awareness of living inside the tides of history comes across again in Love’s Requiem, a portrait of Anurendra’s daughter’s boyfriend at his father’s funeral. The young man is painted in front of an archival photograph of a Tamil lady in Sri Lanka circa 1860, while three generations of the artist’s ancestors look at – and judge – this white man. Yet again, Anurendra’s obsession with history can’t be denied, the painting asking questions about race, whiteness, trust, and generational trauma. Nothing – especially love – exists without a historical context. Anurendra captures history as a vibrant and living thing that connects us all. It’s history as an unstoppable force we participate in, negotiate with, and struggle against in a desire for change. And in this painting, some things can indeed change rapidly in three generations.

What I enjoy, too, about Anurendra’s work, is his self-interrogation: of class, of coping-mechanisms, of political optimism. On the upper floor of the exhibition are a series of pre-coronavirus paintings. Critiquing middle-class activism, Saturday Afternoon Activist, is “a self-portrait of my class…who, once a month, every month, on a lazy Saturday afternoon champions the worthy cause of that moment, talks about it over dinner with friends in a nice restaurant and afterwards, sleeps like a baby.” With his particular blend of satire, Anurendra highlights the delusional grandeur of the middle class, whose activism can be indulgent, performative, and less noble that we might assume. “We were ‘activists’, part of online tribes that knew for sure that we were part of the solution and not the problem…. never, the problem,” Anurendra writes in his exhibition essay.

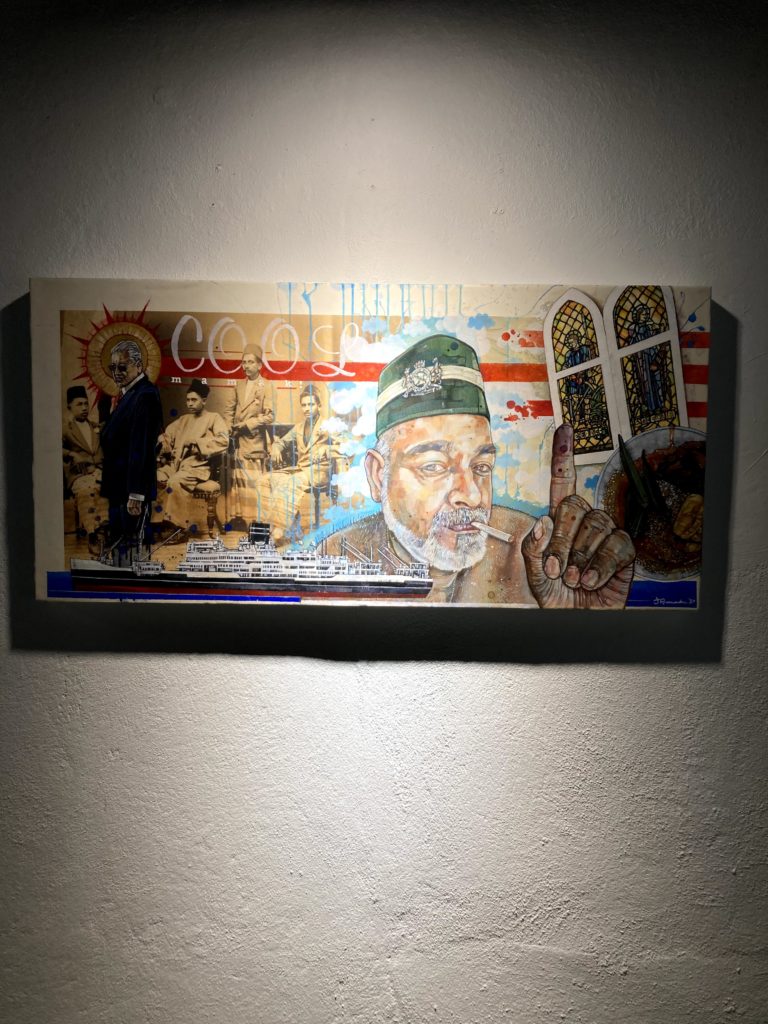

Another powerful piece is Mamak Kool. It’s a wonderfully vibrant piece, with a self-portrait of Anurendra slightly off-centre, holding up a finger that has been inked to signal that he’s just voted in the Malaysian elections. He wears a military Songkok, and is surrounded by a litany of images: Mahathir with a saint-like halo, a photo of Indian Muslims in the colonial era, a submarine, colored windows of Christian saints, and a bowl of Laksa. “The narrative meanders through racial stereotypes and colloquialisms and lately, in light of most recent developments – a wistful longing for what might have been,” Anurendra writes. It depicts, in stunning candidness, what has been erased, compromised, and performed in the lead-up to the unprecedented 2018 elections. In Mamak Kool we are reminded to remain sceptical of any political celebration, to remember that no victory is pure, and certainly not in the complicated country we come from.

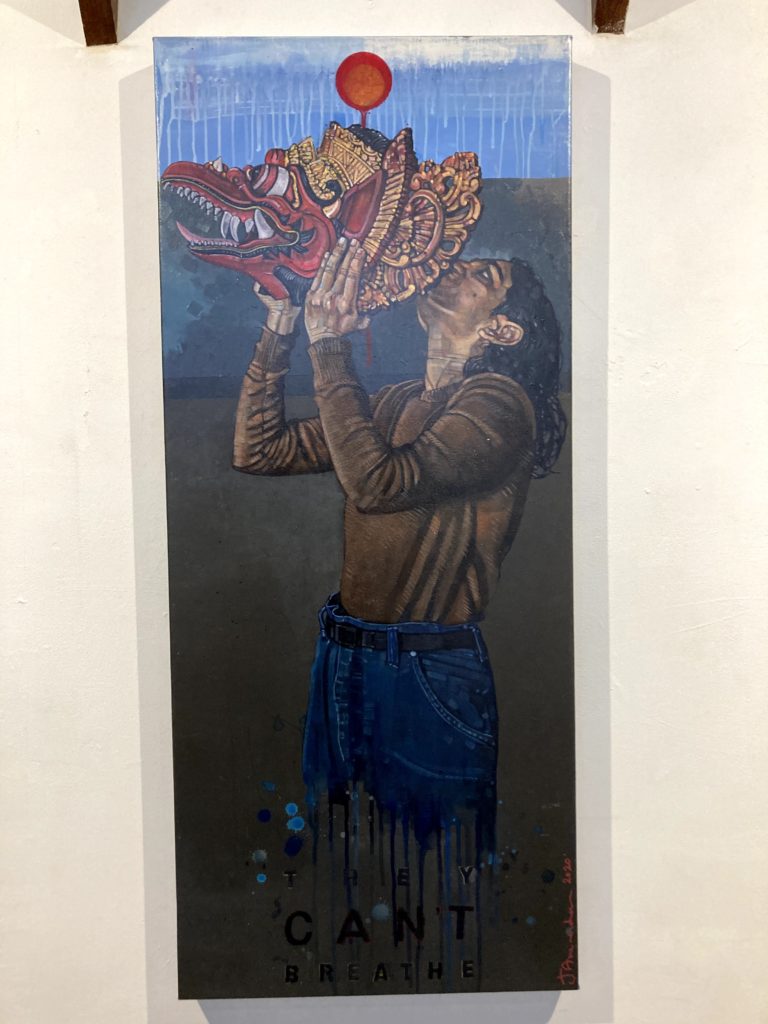

There are too many paintings to talk about in this extensive exhibit, but what is undeniable about Scream, of course, is that it is alive. History here is not the stuffy and staid thing we memorised in school. History here is not even past. It is bold strokes, vibrant colors, bodies of movement, and most of all – it is living, breathing, and surrounds us all like oxygen. And in this particular moment, history is indeed being made: people are challenging centuries-long racial hierarchies, governments and monarchies are being called to step down, and billions of people are trying to survive a global pandemic.

Still, we live. We observe. We scream inside our hearts. And, as the artist writes in his statement, we make pictures.

He writes: “It is the only thing I know how to do.”

SCREAM INSIDE YOUR HEART- New Paintings from Solitary Confinement was featured at Wei-Ling Gallery from Sept 17 to Nov 7, 2020.

Lily Jamaludin is a participant of the CENDANA-ASWARA Arts Writing Mentorship Programme 2020-2021.