By LIM JACK KIN

These are uncertain times. A new conditional MCO looms overhead as businesses and venues across the Klang Valley and Sabah close, and it looks like all of us will be staying at home for the foreseeable future. Shortly before the announcement, I saw two exhibits at the Zhongshan Building that sprang from a similar uncertainty; Hummer by Cassielelolea and Tagistan by Dhavinder Singh had both been developed during the murkiest days of our first MCO. Despite taking radically different forms, both collections told a similar story of introspection, self-expression, and the stories we find in unexpected places.

As the first solo exhibit of Cassie Wong, a.k.a. Cassielelolea, Hummer is an intimate experience, just you and a room full of hummingbirds. It’s tight and focused, taking place in a modest room that doubles as the office of the putticoop design collective. A few ancillary pieces dot the walls and a long desk by the door, but central to the exhibit are nine hummingbird oil paintings that occupy the main display wall. Rather than on canvas, these pieces are painted on old wooden palettes, the kind traditionally used to mix paints before they’re brushed onto another surface. Reclaimed from an art space facing liquidation, these palettes each developed a unique pattern of stains over the years before Cassie repurposed them. She uses the ‘impasto’ technique to paint her birds, applying heavy layers of paint so thick you can see the imprints made by each stroke.

The effect is gorgeous. Using a painting knife, Cassie gives texture to each individual feather. With their radiant, dreamlike mix of colours, the hummingbirds pop into the foreground, contrasting with the older, two-dimensional paint splotches from which they emerge. The birds themselves have varied personalities from playful to regal, arranged to look like a flock in repose. The nuance comes from repetition. “When you look at birds,” Cassie said, “You think they all look the same, but after [painting] repeatedly, it’s like ‘Oh, okay, that’s different.’”

While Hummer is couched in imagery inspired by National Geographic documentaries, it’s also deeply personal. You won’t find any scenic pieces; each palette supports a single portrait, a single hummingbird, inviting viewers to consider it in great detail. As a result, almost every piece in Hummer feels like a close-up shot, brimming with activity.

Of the palettes, she says that while people tend to see them as a transitional stage between paint and canvas, she decided to work on the palettes directly. It would be cliche to say that Cassie ‘breathes new life’ into worn-out materials. Rather, she alters their form, channelling the birth of a new and final brood. A pair of watercolour paintings titled Be and Naught on the next wall highlighted that birth. The former depicted a bird’s nest full of eggs, while on its twin was a dry, empty nest, its contents hatched.

Supporting these paintings on the desk behind me were a series of hummingbirds in fine marker, drawn on the underside of ring-pull caps from beer bottles. The little rings were bent backwards to create a tiny standing frame to view the drawings. Here, Cassielelolea again draws your attention to an overlooked, oft-discarded transitional layer while keeping with her recurring motif of using upcycled materials.

The emphasis on transition doesn’t go unnoticed; Cassie decided to quit her day job this year to become a full-time visual artist. During the most restrictive periods of the MCO, she found herself working incredibly hard. She developed Hummer, took online courses, and spent a significant amount of effort building Le Art Shop, an online art supply store. That diligence makes itself apparent in Hummer, which I highly recommend. It’s a charming and marvellous gem in the middle of Kuala Lumpur. As I thanked the artist for her time and left putticoop, I was struck by how much Cassielelolea, in her industrious and energetic movement from project to project, reminded me of the birds whose portraits she had painted.

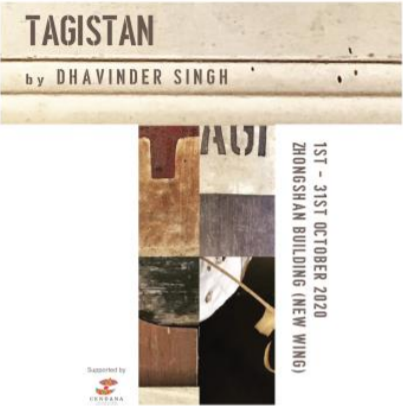

Down the stairs, out a back door and past a narrow alleyway, I headed into the Zhongshan Building’s new wing for an entirely different exhibit: Dhavinder Singh’s Tagistan. Gone were the idyllic natural subjects. In their place was an expansive installation project from the veteran artist, filled with drawings, sculptures, and stop-motion animations that told the story of an industrial hub past its prime, and all the memories contained within.

As a child, Dhavinder Singh witnessed a development boom towards the 90s that brought ironworks and automotive workshops to Jalan Chan Sow Lin, an area he had childhood ties to. Today, its legacy is one of abandoned warehouses and heavy reconstruction projects that threaten to wipe away the stories Dhavinder grew up with. Making use of his unique personal connections to Jalan Chan Sow Lin—his grandfather was a moneylender, factory caretaker, and community figure who would help new immigrant families settle in the area—Dhavinder gained access to a number of old homes, shophouses, and industrial sites to gather materials and objects to build Tagistan. It’s a name that loosely translates to “Land of Storage”, and conjures to mind that famous phrase: “The past is a foreign country.”

And what’s this country like? Stark, striking, and rusty. Rust covers many of the scavenged objects making up the exhibit, making Tagistan feel vaguely post-apocalyptic. As a material, all that rust provides colour, texture, and even thematic commentary; Dhavinder doesn’t perform any ‘restoration’ work on the items he finds, instead letting them stand on their own as a testament to the years they went unused and neglected. While Hummer’s approach was to imbue an office space with life, Tagistan presents us with the artifacts of an abandoned time.

That’s not to say that the objects aren’t meticulously arranged or combined in ingenious ways. Take Tagistani Floating Chess for example, one of my favourite works from the collection. It’s an interactive piece that consists of a chess board suspended on a wire along its centre, with a rusty (of course) box on the floor below, full of old wooden Chinese Chess tokens. Ammelia, Tagistan’s gallery attendant, explained the rules and invited me to a game with her. As we played, the board would tilt out of balance, threatening to end the game prematurely with a hail of sliding tokens. Was this piece a comment on inequality and capitalism, perhaps? The answers aren’t so clear-cut.

“It’s just there,” Dhavinder says. “You can point out many directions, many definitions, but I’ve just left it there in a kind of playful way. It was probably a favourite pastime in the factory in those days. I’m assuming they used to play Chinese Chess, because that’s where I found the game pieces.”

You’ll find that shift to the intensely-personal in a few other spots. While works like Baptism Can Happen Here, It May Require Some Soap or attack the established norms of government, industry and culture imply a sort of societal critique, Dhavinder makes great effort to highlight the individual stories behind the objects. Glancing upwards at a bird-house hanging from the rafters, he says, “I’m speculating that the owner of that factory actually hand-built this, and that he reared pigeons.”

It’s a uniquely transporting feeling to be thinking in big abstracts like culture, industry, and gentrification, only to be reminded these objects didn’t just represent ideas, but specific people. With old government-issue paint cans, an 80s-era workshop monitor, and a vintage first-aid box filled with a bag of salt, Dhavinder Singh manages to tease out the individual histories of Jalan Chan Sow Lin, while weaving them into a story about his own upbringing. I visited Tagistan twice, and still feel like there’s so much more to see.

Hummer was a hike in the woods, Tagistan a ghostly urban expedition. Yet, there are remarkable similarities between the two exhibits. Both feel like the result of profound self-reflection on the part of Cassie and Dhavinder, expressions of a complex personal history laid out across the objects they were drawn to. These two exhibits at Zhongshan end up complementing each other perfectly, each capturing a unique moment in time.

Both exhibits ran in October/November 2020.

Lim Jack Kin is a participant of the CENDANA-ASWARA Arts Writing Mentorship Programme 2020-2021