By ELLEN LEE

“Sesumpah” means “chameleon” in Malay, but in Se{SUMPAH}, a group exhibition which recently had a run at the Black Box MAPKL in Publika Mall, Kuala Lumpur, an emphasis was placed on the word “sumpah”, which on its own is a Malay expression for an oath of truth.

The “sumpah” within the “sesumpah”, or how truth camouflages itself within our everyday reality, was the thematic bent of the exhibition. Organised by Fergana Art and curated by founder Jaafar Ismail, Se{SUMPAH} featured a vibrant line-up of 16 artists, but was ultimately bogged down by unimaginative curation.

The exhibition opened with paintings by emerging talent Syafiq Mohd Nor of abandoned auto vehicles rusting quietly amidst green foliage. Nature recovers and reigns supreme, decay and death are the peaceful constants of life. In this sense, the idea of shapeshifting can be read as the absorption of man back into nature.

This thread is picked up later, in a series of circular paintings by Leon Leong, titled “Aisyalam: The Tree Nation”, featuring human figures contorted like the gnarled branches of trees, reminiscent of a milder version of something from horror mangaka Junji Ito. Then, there were the squishy, meaty paintings of Azam Aris, which gave you a sense of being deep within a creature’s bowels – red, pink, brown and bumpy. The intestinal folds and curves of his brushstrokes are like the tuberous plants encircling the abandoned automobiles in Syafiq’s paintings or the fat knots of Leong’s figures. These are paintings with dark and brooding atmospheres, but within the space and bright yellow lights of the Black Box gallery –spotlights that are more appropriate for theatre than an art exhibition – they felt small, their impact blunted and stripped of depth under the harsh artificial glow of the lights.

In alternative interpretations, the idea of chameleons was used as a metaphor for the double nature of citizens who are also political subjects. Take, for example, the bold paintings by Jehabdulloh Jehsorhoh of Pattani women covered in headscarves decorated with weapons and explosives. Only their bright, neutral eyes peek out. Another one of Jehabdulloh’s fellow artists from the Pattani region of Southern Thailand, Korakot Sangnoy, exhibited a pair of textile pieces, one on red cloth and one on green cloth, both with text and the outline of a man stitched onto them in contrasting colours. The red cloth is stitched with green thread, and the text reads, “The red man wore green clothing, but he never thought that he would have his own green clothing”, and vice versa with the image on the green cloth, is stitched in red thread. It’s possible to interpret this as a critique of partisan politics, where citizens are forced to choose sides, even if both sides do not represent their real interests.

The show features four artists from the art collective Patani Artspace, but they are strange and awkward additions. While their works offer strong dramatisations on the curatorial theme, the phenomena being alluded to in their art – phenomena such as guerrilla insurgency, or the role of women and children in conflicts – are of a bigger, more serious scale than the other works on show, and it’s obvious. Their baggage sits uneasily within a context that doesn’t feel commensurate with it. The inclusion of artists from Pattani, a hotly-contested region, in a show otherwise full of Malaysians, seems to make a political statement that’s never substantialised, thus cheapening the purport of the works.

Without meaning to, the show ends up making one wonder what the purpose of curation really is. Does curation simply entail choosing a “theme” and then sourcing artworks that fit, like a visual art version of a Spotify playlist? While the works on show could all be linked, some more tenuously than others, by this common thread of “sesumpah”, the curatorial voice itself was weak.

Despite the numerous texts plastered around the show, the content and purport of those texts were meandering and slipped through one’s mind like water; understanding couldn’t be grasped. The opening text, for instance, waxed lyrical about the meaning of the exhibition’s title and about the challenge of discovering truth in our current world, but then abruptly ended with, “And so, how does Truth appear in a Chameleonic world? It’s contingent on the literati, not the glitterati, to step up. Then.” A strange final note to end on, highlighting the role of literature in an art exhibition.

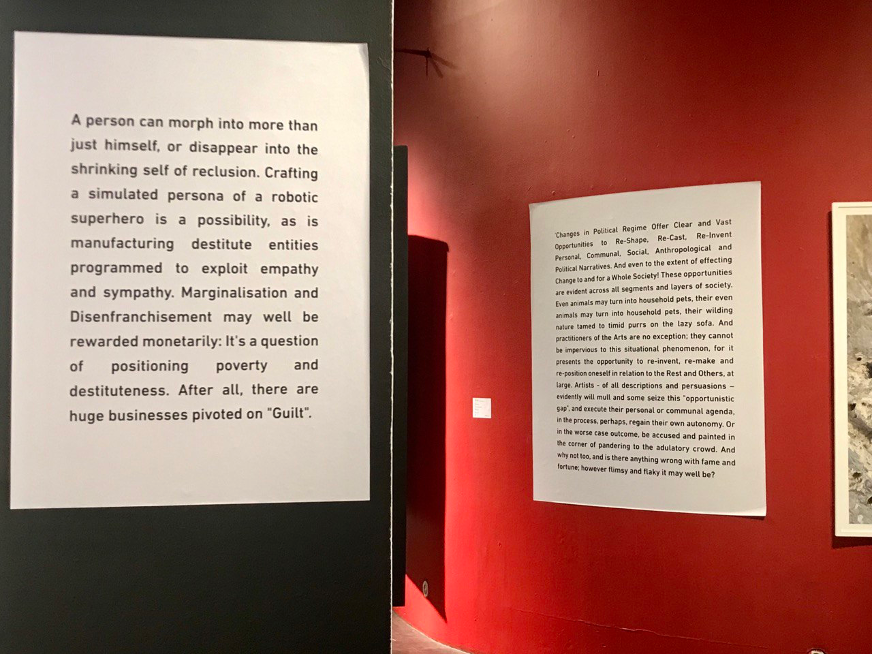

The rest of the show was peppered with similarly un-sexy and anticlimactic statements, such as, “Crafting a simulated persona of a robotic superhero is a possibility, as is manufacturing destitute entities programmed to exploit empathy or sympathy,” or, “Changes in Political Regime Offer Clear and Vast Opportunities to Re-Shape, Re-Cast, Re-Invent Personal, Communal, Social, Anthropological and Political Narratives” [title case sic].

Instead of complicating the idea of the chameleon, shape-shifter or adapter, the show’s curatorial text went off on vague diatribes about the role of artists. It made the show feel wobbly, like a table with individually mismatched legs. Each work seemed to stand on uneven ground with the next one. There were so many forms of shape-shifting, from Noor Mahnun Mohamed’s drawings of Siva in variegated motifs, an exploration of the way gods and archetypes shape-shift throughout time and culture; to the unfathomable ambiguities one is forced to adapt to in immoral or militaristic situations such as with the Pattani artists; to Che Ahmad Azhar’s interpretation of “shape-shifting” as a metaphor for gentrification in his series of negatives of Kampung Baru. The artworks could all be linked through small games of spot the difference and/or similarities, but the links didn’t move towards any direction.

Would it have been possible to enjoy the show more earnestly if not for the curatorial texts? Could a viewer just ignore them and still get something out of it? Sure. On their own, the works on show are uniquely impactful and beautiful. But the show is symptomatic of a trend, especially with group exhibitions, of simply coming up with a theme and then commissioning artists to interpret it. The task of “curation” only comes after the fact, once the curator finds himself with the task of relating disparate works and artists.

Nonetheless, the show was still worthy of viewing and contemplation based on the strength of the works alone, but one did not leave with any new revelations or challenges to one’s established forms of thinking.

Without a strong sense of curatorial purpose, the show felt a bit like channel-surfing: viewing exciting but disjointed images flickering past without a coherent narrative. There is a space in art for these kinds of shows – they are often commercial, and so (the idea of) curation is used as a way to intellectually embellish over the banal fact of the artworks as commodities. Se{SUMPAH} had its own chameleonic quality, blending in with a lot of other forgettable group shows in this intermission of a year.

Se{SUMPAH}, a group exhibition organised by Fergana Art, ran from Oct 12 to 27, 2020 at Black Box MAPKL, Publika Mall, Kuala Lumpur.

Ellen Lee is a writer under the CENDANA-ASWARA Arts Writing Mentorship Programme 2020-2021