Oleh Farah Dianputri for Lensa Seni

Being a woman is a terrifying experience. Equally, it’s difficult to articulate. How can you feel safe to express yourself when people are so quick to blame hormones? How can you convince someone the threat of a stalker when Malaysian law doesn’t even recognize it as a criminal offence? How can you be a ‘modern’ woman without being accused of slandering your heritage? Is ‘having-it-all’: work, family, love, beauty; really worth your sanity?

It’s only fitting that one natural reaction to express this conundrum is magical realism. For the purpose of my analysis, I will be using magical realism as depicting themes from reality in fantastical ways. It’s not a retreat into imagination, it’s about endowing the harsh realities in a symbolic visual form.

Eng Hwee Chu’s paintings are the product of a malignant imagination. Her body of work and depiction of her own body are caught between the outrageous expectations of maternity and modernity. Her avatar can be seen fleeing her own shadows, constricted by the trappings of Christianity, plagued by hungry ghosts. Phantasmagoric figures overpopulate the canvases. Combined with impossible architecture, where domes materialize from the sky and edifices are left only half standing, the compositions produce a dizzying kaleidoscopic effect. Her body floats, soars and contorts its way around married couples, children and ancestors. Through this, we are drawn deep into the anxieties that are specifically concerned with the place of the female body in modernity. During one of her presentations at the second Asia Pacific Triennale in 1998, she notes how even with the shifting mores of gender equality in the global sphere, there’s always a complicated renegotiation with the past that always bubbles to the surface. Twenty-two years onwards it’s still an apt assessment.

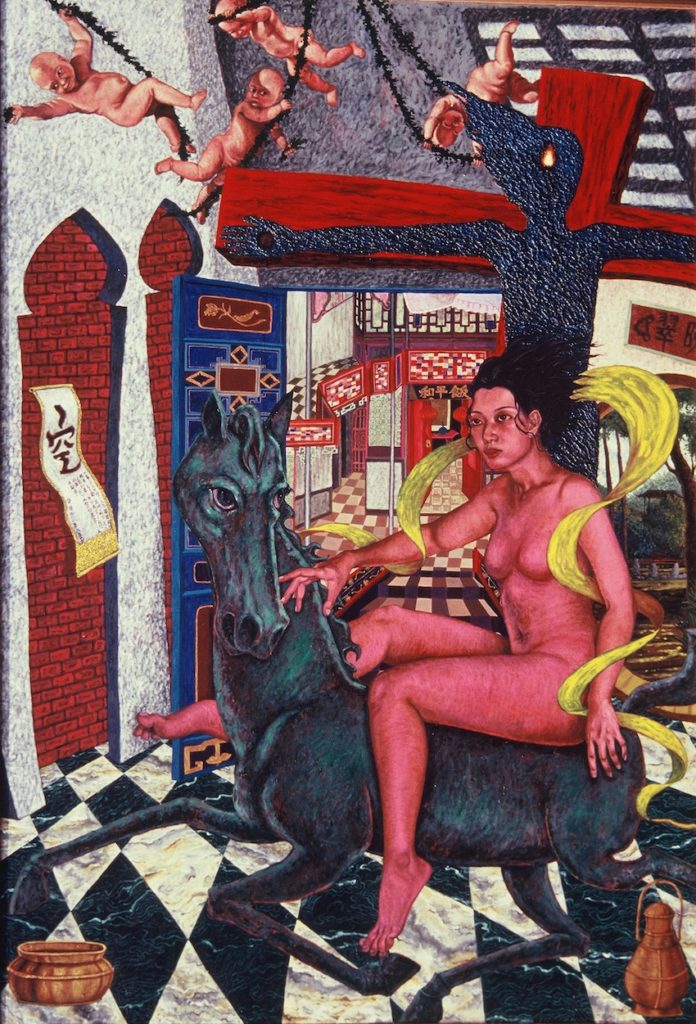

I’ve always been fascinated by one of her older paintings, ‘Prospect’, created in 1995. A woman with the levitating scarf, referencing depictions of the moon deity Chang-Er, sits atop a famous piece of Chinese bronze work, the Flying Horse of Gansu. Behind her, a shadow is nailed on a crucifix, and putti you would find in Renaissance painting are swinging on vines. The architecture in this painting consists of arabesque niches and a confusing perspective into Chinese courtyard. There is patchwork of many cultural references from places that span from one side of the world to another, to try and to situate her equally disparate sense of identity. But what if we perceived them as they are depicted, as part of a whole composition? In Homi Bhabha’s ‘The Location of Culture’, Bhaba invites us to challenge the notion of centers and peripheries, and acknowledge the fraught stories of migration that intrinsically link our often grossly oversimplified views of cultures.

This is why magical realism is the perfect medium for this purpose, it’s an attempt to make us see that all these elements we think of as belonging to separate locations can belong as a whole. The same could be said about what it means to be a woman. You can still hold all these contradictions and be whole, which lay at the very foundation of her oeuvre.

We can see Eng Hwee Chu build on the composition of ‘Prospect’ in a later work. You could breakdown the core elements of ‘Searching Facing the New Edge’ as echoing ‘Prospect’. Christ, the suspended shadow, references to Chinese cultural heritage (in the form of Beijing Opera characters) and the flat perspective reoccur in this painting. Instead of the shadow being nailed onto the crucifix, it seems as though it has already served it’s time on the cross and is plummeting to the ground. Instead of the pose and confidence she has in being endowed with the symbols of her Chinese heritage in Prospect, she is stripped bear of everything and turns away from the Beijing opera actors that look down on her like disapproving parents. The two paintings are made form the same ingredients, but the transition between Prospect and Search veers towards a more troubled sense of identity, as if the pressures are continually mounting.

Symbols are often described as enchanted objects, their power deriving from being imbued with meaning. However, Eng’s symbols are magical realist objects, their power derived from a mirroring with a social reality. From the nineties to today, Eng Hwee Chu utilized magical realism to fearlessly explore the pressures and anxieties faced by women, rooted in a dialogue with heritage. Vulnerable and wary, modern and embedded in traditions. Incandescent, in her bare-naked red flesh.

It feels like that sometimes doesn’t it? Failures of our personal lives, be it in love or family can feel like a cosmic game played against us by our fate. There are hauntings that take place we are unaware of: an entangled web of our parents’ relationship, our grandparents and the phantoms of the arranged marriage and the love marriage. We’re just bodies thrown into chaos to collide with other bodies. And with them their expectations, hopes and fears. Through her magical depiction of female bodies in space, Eng Hwee Chu gets to the core of something real about a woman’s fate in our times.

Featured Image: Credit to Suma Orientalis

Writer is under the CENDANA-ASWARA Arts Writing Mentorship Programme 2020-2021

The views and opinions expressed in this article are strictly the author’s own and do not reflect those of CENDANA. CENDANA reserves the right to be excluded from any liabilities, losses, damages, defaults, and/or intellectual property infringements caused by the views and opinions expressed by the author in this article at all times, during or after publication, whether on this website or any other platforms hosted by CENDANA or if said opinions/views are republished on third party platforms.